SyriaUntold originally published this piece in Arabic here.

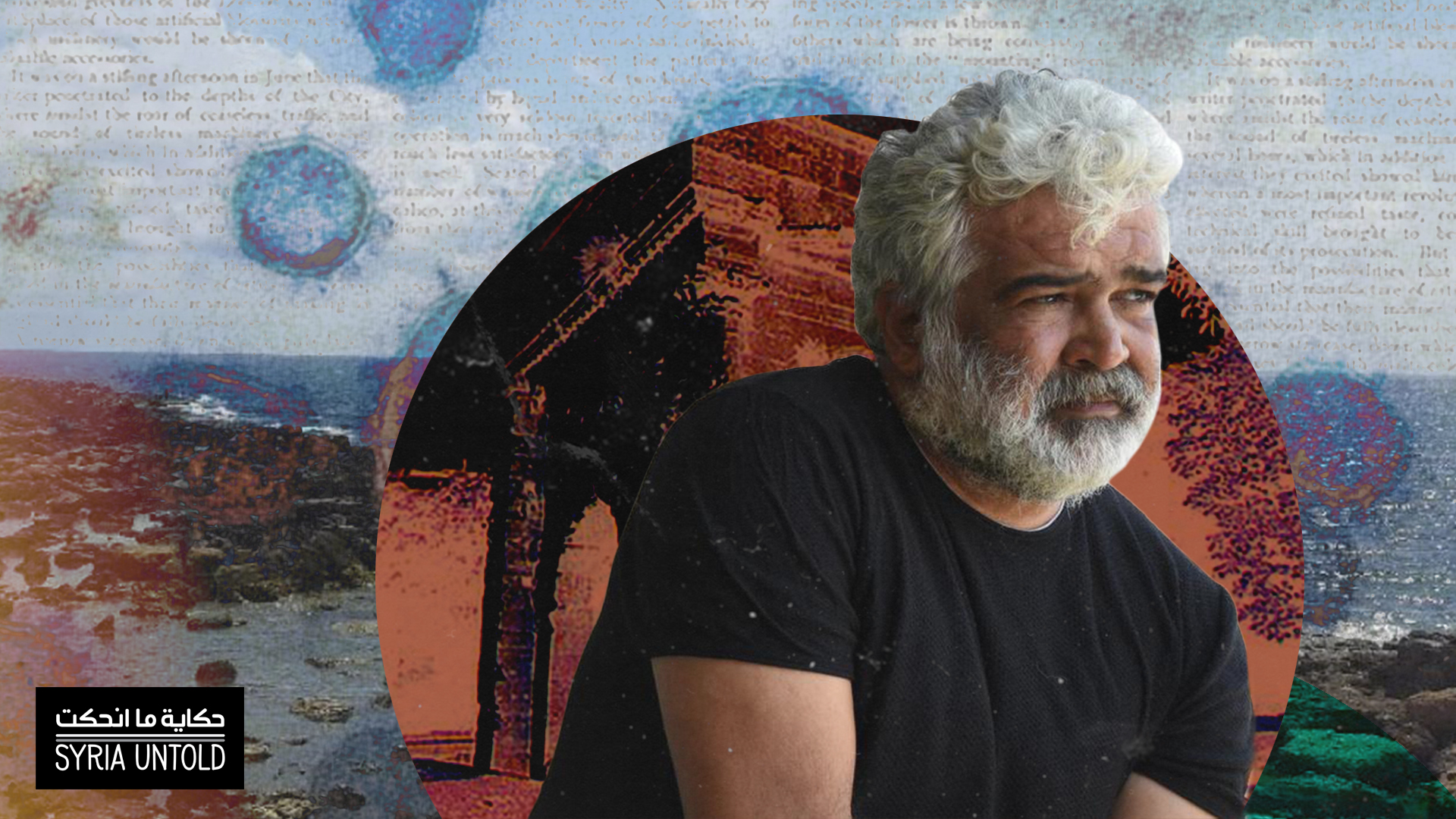

It is hard to introduce an interview conducted with a figure we love, let alone a figure we consider an idol.

I don’t know what prompted me to request an interview with Randa Baath. I was fully aware it would be difficult for both of us, due to the special bond I have with her and her family, but I decided to move forward regardless. I decided to put my personal feelings aside and focus on her work in translation and her relationship with Arab culture, knowing that she translated several books from French into a solid Arabic.

Baath has been working in translation for decades. Her language is simple yet powerful. She is fluent in the two source and target languages.

“At the age of 11 or 12, I would often translate some French writings or songs I was fond of into Arabic. I have mastered it as much as a foreigner can, and I embraced the Arabic language ever since I was a little kid because I grew up in a house that adores it and does not tolerate Arabic mistakes,” Baath told me during our interview.

Baath generously answered my questions despite my numerous requests and some personal difficulties she has recently gone through. Baath lives in Damascus, her beloved city. We communicated through Facebook Messenger, WhatsApp and by email. We also exchanged some calls and voice messages.

I tried my best to come out with a piece as neutral as possible. And I put my love for her aside, or at least I attempted!

What does it mean to work in translation in Syria, at a time when prices are skyrocketing and basic life necessities are running out? And what is the added value that culture or translation might give to a country ravaged by poverty?

I have been working professionally in translation for nearly 20 years. In other words, translation is my source of livelihood. Over the first decade, I was working hard to prove myself. I managed to achieve my goals through dogged perseverance, commitment and continuous effort, and then I pursued my Master’s Degree at the Higher Institute for Translation and Interpretation.

Throughout the two years of study at the institute with my classmates—most of whom were my children’s age—I witnessed their anxiety, pain, confusion and enthusiasm. I also witnessed their bigotry and tendency toward rumors and provocations.

I studied at the institute to obtain a Master’s Degree in Interpretation, knowing that the “market” in Syria is virtually monopolized. I assumed that my studies there would unveil my skills to the teachers. However, the field of interpretation was almost completely closed after 2011, so I started teaching at the institute upon my graduation, and I shifted to translation.

Syria’s year of pain, through the eyes (and pen) of Khaled Khalifa

21 November 2020

The vast majority of Syrian publishing houses are unfortunately faltering nowadays. Neither fresh graduates nor experienced translators are getting their financial rights. However, when the security and financial situations worsened, I had luckily already established myself in this field and published a considerable number of books, which led publishing houses outside Syria to offer me to work for them and translate books that were of value to my own knowledge and to the knowledge of Arab readers.

I am honestly managing perfectly so far. But new translators—and some of them are very distinguished—will unfortunately not be able to meet their needs if they only work for local publishing houses or the Ministry of Culture, which is why they opt for other professions or for sworn translation. Remarkably, a large number of my students applied for the sworn translation competition, and they all succeeded.

As for the second part of the question, I believe that the task of culture, in all its forms, is aimed at self-discipline. Take music, theater, cinema and singing, for example, and notice how young men and women rushed to attend events even when deadly shells were pounding the city of Damascus (and I specifically mentioned Damascus because I lived there throughout the war and still do despite all the hardships).

In my field of specialization, my students tell me that the culture that I conveyed to them broadened their horizons and opened their minds to things that they might not have thought of. Until today, I have a relationship of love, trust and cooperation with them on all levels, or so I imagine!

You have been translating from French for many years. What is your take on translation from French into Arabic, knowing that French is one of the languages most translated into Arabic? Also, what is your take on Arabic-to-French translation, since you know France well?

I think that translation from French has regressed greatly in favor of English, and maybe Spanish, as far as literature is concerned. After the closure of the French Cultural Center in Damascus, access to the latest publications, such as books, magazines, music, films and others has unfortunately become almost limited to those who travel to Lebanon (even a year ago) or to France. The French Center was a breathing space for French culture and thought, and it supported the translation of some books.

I believe that literary translation is part of literary writing.

However, translation is not limited to books. There are studies, articles and contracts, among other things, that need translation. However, the volume of this type of translation from French into Arabic is limited compared to translation from English. English has become the language of commerce, deals, research and advertising, and the list goes on.

For its part, Arabic into French translation is in my opinion limited to the Sinbad series, which is supervised by Farouk Mardam Beyk. It is issued by the Actes Sud house, which specializes in translating Arabic literature into French, as well as in translating topics related to Islamic culture in general and young writers, especially women.

The only book I translated from Arabic into French was a booklet on the Al-Hosn Citadel [Krak des Chevaliers]. I have worked on a good number of translations from Arabic into French, but they are not the type that requires the publication of the translator’s name (contracts, studies, pleadings, etc).

In these interviews, which I recently started conducting, I am trying to focus on Syrian literature and the makers of Syrian literature. And ever since I started, I have been wondering whether Syrian translators fall under the category of makers of Syrian literature. Is translation into a country’s language deemed a contribution to the making of this country’s literature? Or is it “foreign literature” or “parallel literature” to “the country’s literature”?

I believe that literary translation is part of literary writing. But I do not think that a translator’s style should overshadow an author’s style. A translator should try as much as possible to convey the style of the author they are translating. Unfortunately, there are translators who give different novels the same style because their style overshadows the authors’. This prevents literary translation from being an addition to “the literature of the country”—as you put it in your question—or to the Arabic literature if the translator is translating a novel into Arabic. This would not be the case, however, if a translator managed to convey the style of a foreign author, knowing that this is a style that differs from one writer to another and from one country to another.

A small cafe in Damascus

01 January 2021

On hating my name

11 September 2020

Consequently, I find that having one translator work on the novels of the same writer can yield positive repercussions. For example, I am currently translating a novel by a writer from Central America. Her style is distinct from the styles of authors I previously read. And I think that my translation of other novels by the same author would be smoother and easier for me than this novel.

How do you perceive the Arabic spoken and written culture at the present? How can intellectuals living in countries at war, such as Syria, Yemen and Libya communicate with the Arab and international culture movement? Do you feel culturally isolated in Syria?

I cannot claim that I am aware of everything that is currently being produced in the Arab countries. Neither my time nor my circumstances allow it. However, I believe that any cultural act, especially in countries experiencing war, is vital.

I remember when Youssef Abdelke set up his exhibition a few years ago in a hall in Damascus, and how some tried to attack him because the opening of the exhibition happened to coincide with the resolution of the conflict in Aleppo.

Was it shameful for me to attend the opening ceremony? Was it an act I should apologize for, or was it a need to feel my humanity and that my feelings were not weakening? Is attending a concert or a play a luxury and a type of indifference, or is it a renewal of energy that we need in order to go on amid conditions that are inhumane, to say the least? I agree with the second opinion. Were it not for these cultural outlets, I would have felt that I was nothing more than a machine.

Communication with the Arab and international culture movement is ongoing, thanks to technical means that allow it, especially the internet. New generations introduce people of my age to new experiences. Thanks to the internet, I do not feel culturally isolated in Syria.

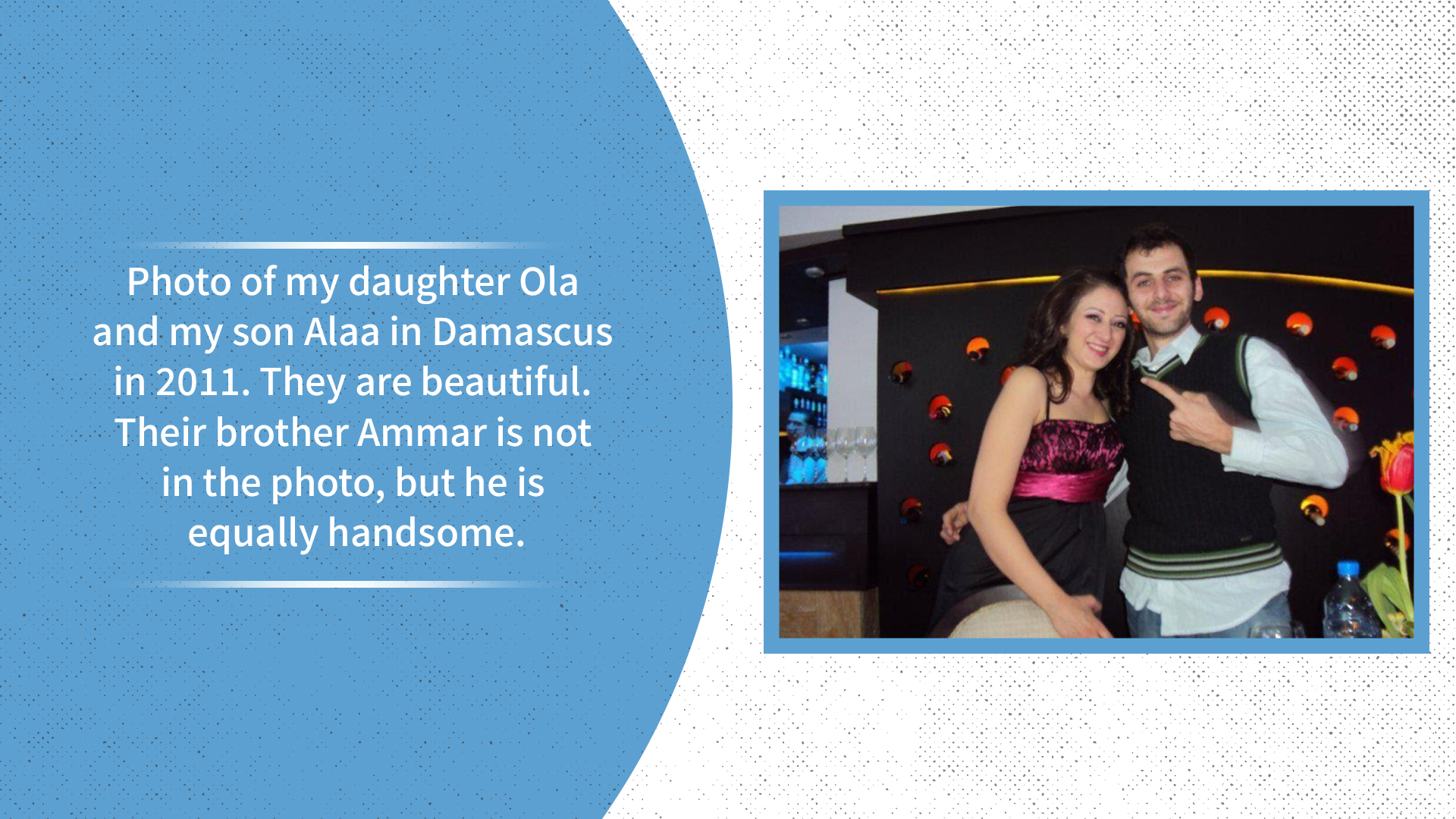

I've known you for a long time. And I know that you are a great mother—even if you do not agree with me—and I know that you serve as a mother to your children’s friends as well, and I know that many of your children’s friends wish you were their biological mother. Patriarchy is omnipresent, and good moms are perceived as moms who should not work. You are not only a great mother and have translated about 20 books so far, but you also teach and originally worked as a laboratory pharmacist. How have you managed to juggle all of these things? How do you have the time?

Thank you for your praise for my motherhood, and I think that you see me this way because you love me, and this will often prevent you from looking at me objectively.

As for the second part of the question: I’ve translated far more than 20 books. And I’ve managed to juggle motherhood and work partly because I grew up in a household that attaches great importance to time and knows how to exploit it both in times of serious work and times of rest and amusement. Another reason why I managed to do so is because I majored in pharmacy. This profession teaches one to be precise and to use lost time for something useful. But most importantly, I usually only do what I love to do. I liked the profession of laboratory pharmacy and I believe I succeeded in it. Also, translation has been my “passion” ever since I was in my early 20s and was learning French.

At the age of 11 or 12, I would often translate some French writings or songs I was fond of into Arabic. I mastered it as much as a foreigner could, and embraced the Arabic language ever since I was a little kid because I grew up in a house that adores it and does not tolerate Arabic mistakes.

This mastery is essential in the translation process. A basic and important factor is that I received invaluable help from my mother-in-law, who took care of my children when they were young so I could go to work without a single concern. And when I became a professional translator, they had all grown up and were independent.

Testimonies about Randa Baath and her life

Loyalty is the most important lesson she has always been keen to teach us.

When I mention the name of Mrs. Randa Baath (Madame Randa as we call her), this is the sentence that immediately occurs to me. She has been keen to always remind us that what protects our reputation as translators is being loyal when conveying and translating content.

Mrs. Randa taught us Translation and Arabization during the second year of our MA in Translation at the Higher Institute for Translation and Interpretation. Our lessons with her were interesting and informative, and they included various historical, geographical and economic texts, contracts and letters as well as a rich list of new words.

Every text, sentence or word she said had a story, and every story summed up her experience in life and work as a translator. With her, we got to know many personalities, be they writers, actors or poets, in a different way. She made us feel they were real. She made us feel they were our friends and not just people we study.

She was firm when it came to assignments, lessons, the French pronunciation of words and the structures of sentences in both Arabic and French, but she was also close to everyone. She was like an old friend to us. Her calm smile helped us act naturally with her, and her experience in life and work enticed us to trust her words of advice (even when it came to personal matters). She was also keen to offer competent students opportunities to work in translation.

She always asked us if any of us lived on her way, so that she could drive us with her in her car. There are several times when I went with her to the institute. I once even went with her, along with a classmate, from the institute to have a "Halabi" lunch. She visited me at my home, and I visited her at her home.

Madame Randa is a generous and friendly teacher, and a rich person in every sense of the word.

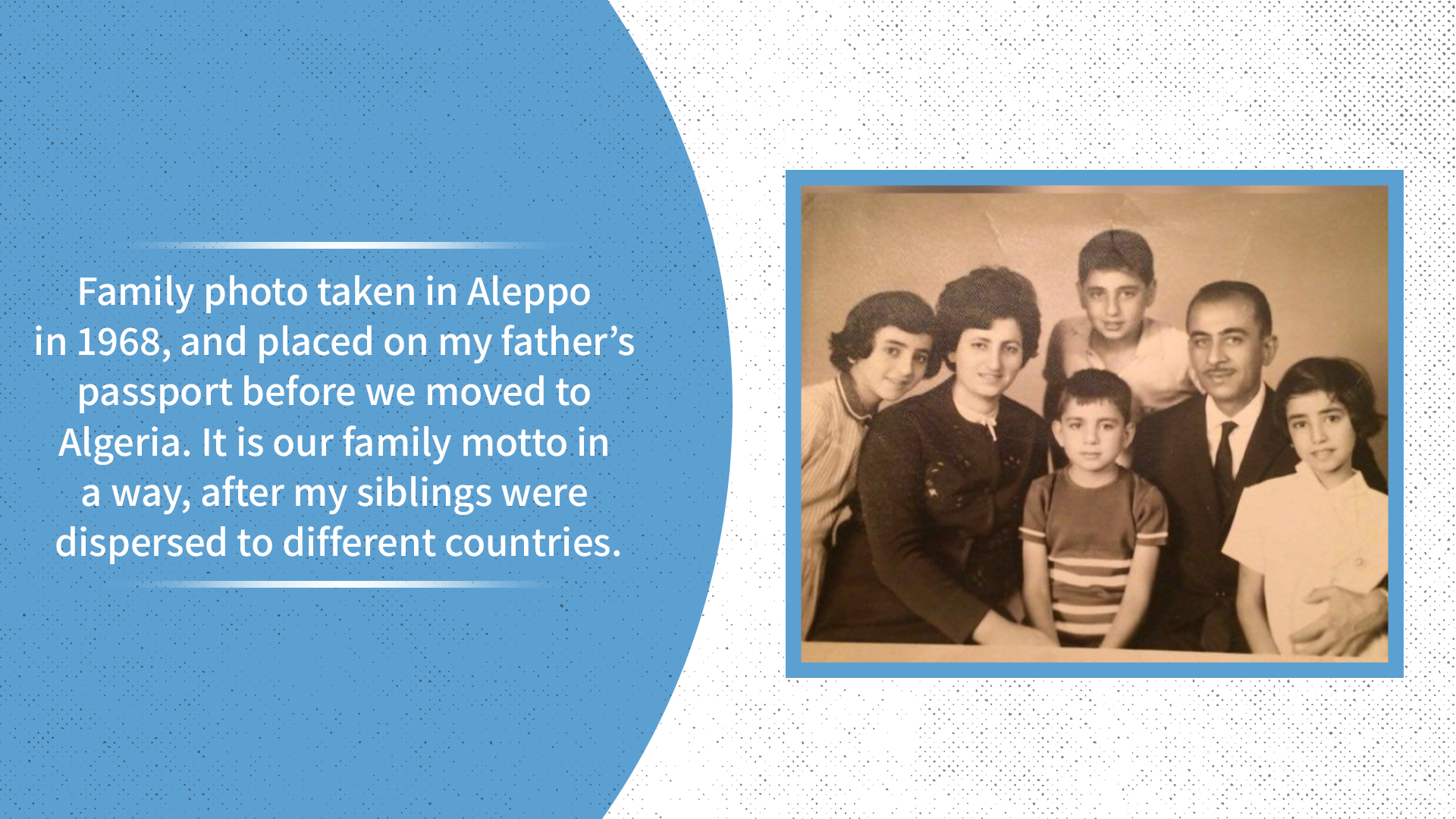

I completed my fourth year by the late 1980s. I do not have vivid memories of that period but I do get some flashes of it: spring worms on my fingers, the sound of summer wind deafening my ears, a bacterial colony under my mother’s lab microscope, a butterfly needle that she used to take a blood sample for my periodic blood tests. I meet my father on a visit to Saydnaya Military Prison. Darkness. Blackout. My mother turns on the Lux gas lantern that has a distinctive sound. She begins to read to us while she knits. I remember her voice in the dark telling us a story that I cannot read because it is in French.

She would read to us the famous story of The Little Prince, who lives on his own planet and visits Earth, only to be surprised by human nature. He was a different, isolated, frightened dreamy prince. I was envious of his planet, and envious of my mother for speaking French.

Today, thirty years later, I remember and envy her for her patience and her ability to love in the darkest moments. As a child, I did not understand her war, and I did not understand the depth of darkness that my mother fought on a daily basis. She built us a beautiful world in a small city in a country witnessing two wars, to give us the largest amount of “normalcy” a child could get in a world that is the furthest from being normal.

Was The Little Prince her first translation? Maybe not, but it might be her most valuable translation for me, because it sums up the most difficult thing my mother did: building and protecting a family while teaching love despite it all.

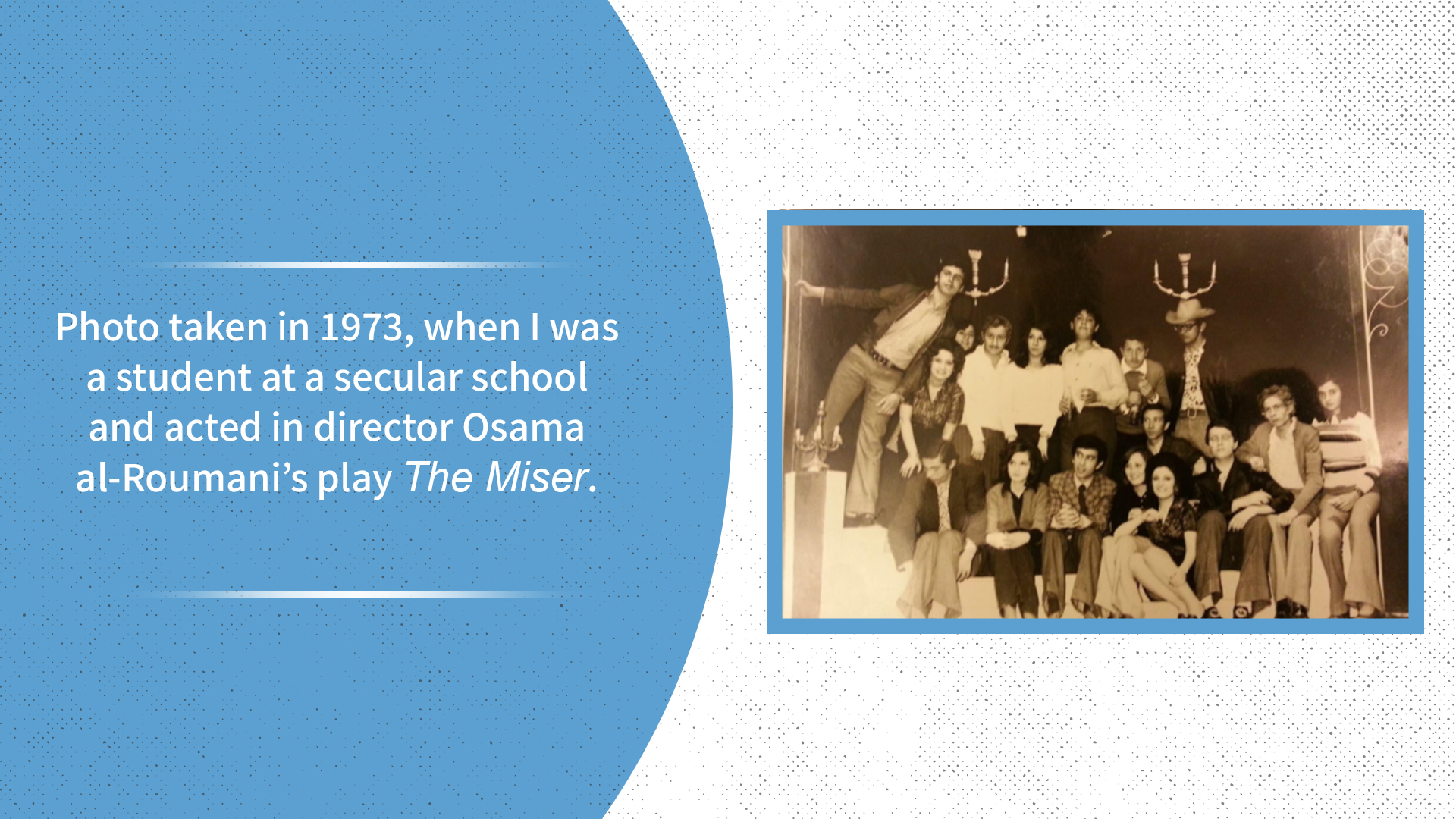

We met about 20 years ago.

By chance, the two different paths of our lives intersected in a translation classroom at the French Cultural Center in Damascus. She was a gentle, sweet-natured woman who had a gentle look and a sad smile.

Only a few people can grab one’s attention from the very first moment. Randa was still under the shock of a traffic accident that claimed the life of her husband less than a year earlier. As a result of the accident, she and her youngest children suffered many injuries. This is what she told me when, after hesitation, I asked her why she was wearing black.

Despite our different personalities, we immediately started to develop an affection for each other and an emotional relationship. And although I had only recently met her, I felt like she was an old and close friend. I liked her frankness, honesty, audacity and the confidence that her method implies, far from falsehood and pretense. And I did not conceal my amazement at her determination to challenge the tragedy and move forward with a determination that not many can have.

What she told me about the details of the first painful experience she went through had a great impact that seeped into the depths of my soul. Her struggle in difficult periods, her bearing of all the burdens and responsibilities that she had to put up with under harsh conditions as a mother of three, and her response to those circumstances with solidity and an amazing degree of fortitude, made her, in my opinion, an example of courage.

Our friendship grew stronger when she asked me to review a book that she was translating; I agreed with pleasure coupled with fear because it was my first time. She has distinct capabilities in this field, as she mastered both the French and Arabic languages. She is intelligent, educated, knowledgeable and a passionate worker. We worked together with a beautiful sense of harmony and a great deal of enthusiasm. Our first book succeeded. And it was not our last, as it was followed by a second, a third and a fourth. Our work together brought us closer. We would go together to watch films and attend seminars and cultural activities. We would read, exchange opinions and discuss topics related to God, religion, politics, history and literature. Our discussions would sometimes shake my ideas and incite me to search for healing answers.

Then we parted ways in translation, as time separated us, and the Syrian tragedy came to further separate us, and now we only meet occasionally.

When I look back today and reminisce about those memories, I remember it all and feel that I am grateful to the coincidence that brought us together, and that I will remain grateful to Randa for helping me enter the world of translation, which was a turning point in my life.

I was, still am, and always will be proud of our friendship.