This article is part of a limited series marking a decade since the start of the Syrian revolution. Read this piece, originally written in Arabic, here.

It has been 10 years since the onset of the Syrian revolution. But what really happened during these years, and how and why did it happen? What were the outcomes, and what are the future prospects?

How were the events and stories of the revolution narrated? What are the narratives that emerged to answer such questions, their representations or related events? Is it possible to compare these narratives to extract a unique objective narrative and dismiss subjective ones?

Or, is it in the nature of narratives to be imagined and to mix reality with fiction, the objective with the subjective, and reality with the ideal situation? What is the importance of one narrative or the other? To what extent does the content of these narratives play a critical role, not only in documenting and understanding oral or written history, but also in situating that history in the present and determining future prospects?

One narrative, or multiple narratives?

The narratives of the Syrian revolution are certainly different, and even conflicting at times. Opposing the narrative of an ongoing revolution is the narrative of a revolution that never actually existed. In between, we come across narratives of a revolution that happened for a few days, weeks or months, or only for a few years. Some narratives say that what happened was a foreign conspiracy, whether that be imperialism, Zionism or reactionism, as opposed to the narrative of a popular revolution against tyranny and for freedom, dignity and justice.

Questions about growing change in Syrian narratives

12 January 2021

Another narrative, of an Islamist or Sunni majority fighting against an Alawite leadership to establish an Islamist state, also emerged, in opposition to the narrative of an oppressed Syrian majority rebelling for citizenship and democracy.

Multiple ethnic, religious, sectarian or regionalistic narratives surfaced, as opposed to narratives based on a feeling of national belonging to Syria in general, and other narratives having a global political and economic perspective.

This article is an attempt to examine some of these narratives and answer some of their questions from multiple perspectives.

Historical narration of the Syrian revolution

Narration can be fictional, as in the narration of stories, tales and other literary works, or it can be historical, as in the narration of historiography.

The text takes special interest in the historical narration of the Syrian revolution. According to French philosopher Paul Ricoeur, the main component of narration is the plot as defined by Aristotle, “the organization of the events,” or e ton pragmaton sustasis [i].

Narration attempts to create a coherent whole of seemingly dissonant events, actions, coincidences, means, goals, values and ideas. By narrative, we do not just mean a tale or story. Rather, it is something partly and relatively close to the “grand narratives” that French philosopher Jean François Lyotard discussed in his book The Postmodern Condition: A Report on Knowledge [ii]. The grand narrative is a general descriptive and evaluative vision, not just of a phenomenon or event, but of history, its meaning, value and philosophy.

In the grand narrative, the subjective aspect might complement or intertwine with the objective one; the ideological might overlap with the cognitive; and the literary might complete the historical, in a way that might suppress many small narratives but give significance to many others.

So far, none of the small narratives in Syria has evolved into a grand narrative. The articles in this series include different main classifications, based on various criteria, of the most prominent and important narratives of the Syrian revolution. The main pieces outlining these classifications in our series include Hazem Nahar’s “Initial approach to our narratives about the Syrian explosion” and Mutaz al-Khatib’s “Narratives of the Syrian revolution.” The portfolio also features Nahed Badr’s “What has happened in the past 10 years in Syria?” Badr's article emphasizes multiple answers to that question.

From small narratives to grand narratives

At the onset, the Arab Spring seemed like a collection of stories, events and small narratives that could not be easily connected by a causal relationship. At the time, there wasn’t a grand narrative linking the slap that Tunisian citizen Tarek al-Tayeb Mohamed Bouazizi received publicly from a policewoman and the slap that a Syrian traffic policeman delivered to a young man in the al-Hariqa neighborhood in Damascus. Nothing seemed exceptional about these two slaps or heralded their subsequent transformation into an integral or foundational part of a grand narrative. The protests in the Arab Spring countries appeared as massive revolutions, albeit within small, rather than grand, narratives. They were revolutions resenting the status quo, rather than clearly setting an ideological alternative of what must be.

What happened is not just a revolution, a civil war or proxy wars. It is all these things and others as well.

They weren’t ideological revolutions in the common and traditional sense of the word. At the onset, they were not viewed as partisan revolutions of the left or the right; secularists or Islamists; atheists or believers; urban citizens or rural folk, etc.

The prevalence of small narratives seemed clear at first, even within the same country. This was evident in the Syrian revolution, at least during its first weeks, when coordination or integration, and organic correlation were missing from the popular movements and protests across the different parts of Syria, where the protesters’ demands also lacked consistency.

The different parties, whether directly or indirectly linked to the Arab Spring, soon began developing conflicting grand narratives in parallel with the conflict between these parties on the ground. Ever since, the conflict between these various general Arab Spring narratives particular to each country has intensified. For many reasons, the conflict between narratives has not led to one dominant grand narrative so far. In fact, the conflict rages on, and the horizons are open, despite all attempts to limit them and make them one-dimensional.

Mourning Hassan Abbas

10 March 2021

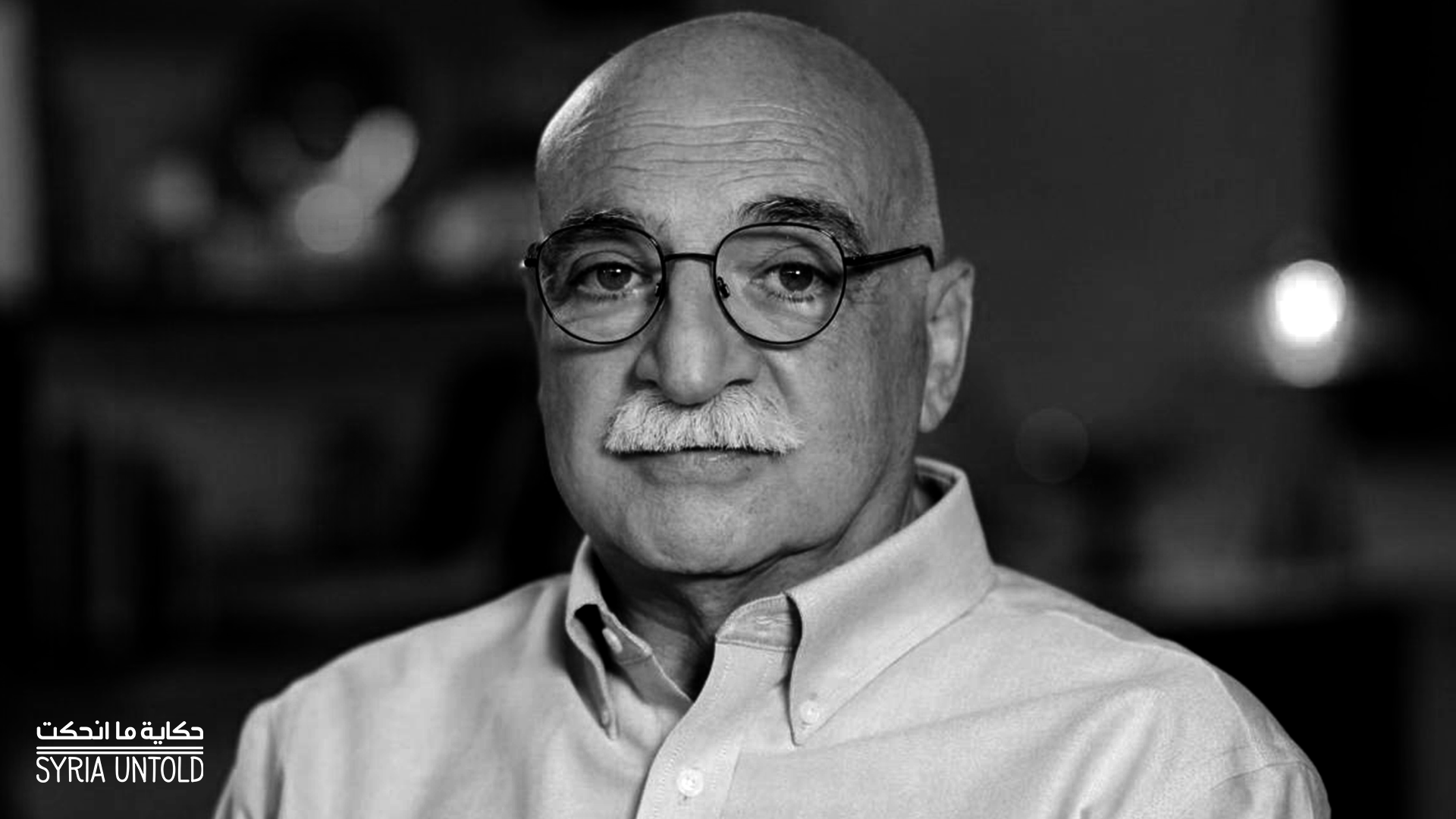

From Aleppo to Beirut, cities burning

26 February 2021

Revolution as a historical event

Talking about open horizons does not deny that the Syrian revolution, as an act of Syrian political actors, has actually ended. But the Syrian revolution was never just an act to be tackled on that basis, in accordance only with its ends and direct outcomes. The Syrian revolution was and still is a historical event that does not end until its outcomes, after-effects and repercussions find their closure.

It seems clear that these outcomes, after-effects and repercussions are far from over. Narratives in general, and Syrian narratives in particular, can tackle the Syrian revolution from the perspective of the theory of action, as an act that has ended, or from the perspective of the theory of history, as an event with ongoing outcomes, after-effects and repercussions.

This series includes two articles that emphasize the event aspect of the Syrian revolution: Ahmed Yousef’s “The Syrian revolution as an event” and “Lahcen Ouzine’s “The Syrian event as a political revolution.”

Descriptive and normative approaches: A constant entanglement

A constant entanglement exists between the descriptive and normative approaches in Syrian revolution narratives, over whether the revolution was described as an event or act in these narratives.

In addition to the clear presence of the normative dimension in the approaches of different political actors, that entanglement between the normative and descriptive is present in so-called analytical approaches, regardless of their attempts to stick to description and analysis, and steer clear of evaluation and normative judgments.

The normative approach is not limited to judging the revolution as a failed or foiled revolution, or labelling it as sectarian or secular, and so on, but also extends to using certain notions or terms. For instance, talking about the Syrian event by describing it as a revolution, or using related terms, encompasses normative (and descriptive) judgments that are very different from those involved in the notion of civil war [iii].

Wissam Saade tackles these two notions in one of our series’ articles, headlined “Dialectic of revolution, civil war and the national entity in Syria,” which includes an extensive critical review of Nikolaos Van Dam’s Destroying a Nation: The Civil War in Syria [iv].

However, away from radical and unilateral normative judgments that are limited to speaking about the supposed purity and grandness of the revolution, or reducing it to a conspiracy or “outburst,” there is indeed increased recognition of the “ambiguity of Syrian revolution,” which is the title of one of our series’ articles, by Morris Ayek.

Admitting this ambiguity requires avoiding and refusing any unilateral normative vision either deifying or demonizing the revolution, the rebels or directly or indirectly affiliated parties. However, if we acknowledge this confusion, base our judgment on it and build on it both cognitively and ideologically, it does not necessarily mean tarnishing our stances and evaluations with the infamous grey cloud. Nor does it mean trying to avoid such stances and evaluations as a matter of principle, from the perspective that “both parties are bad” or “each is worse than the other.”

Greyness here is the greyness in the stances taken, rather than in the lack or avoidance of them. This greyness is connected to acknowledging the ambiguity of the Syrian revolution and admitting the impossibility of totally excluding the normative dimension of knowledge related to phenomena and social events, in general, and to a particular event like the Syrian revolution.

The grey area is a cognitive expression of the great complexities of what has been happening in Syria for the past 10 years. What happened is not just a revolution, a civil war or proxy wars. It is all these things and others as well. It should not be reduced to any single, descriptive-evaluative dimension.

Contrary to what one perceives at first glance, the grey outlook acknowledging the ambiguity of the Syrian revolution can present a clearer and more objective narrative than any unilateral, reductive view. It is far from slipping into cognitive and evaluative indifference that does not distinguish, or does not show the existing difference and hierarchy, between the dimensions of the examined phenomenon and the causal factors affecting it, and between the values associated with it, from a general value perspective, or from the perspectives of political actors.

Between knowledge and ideology, objectivity and subjectivity

Based on this entanglement between the normative and the descriptive dimensions, or the permeation of the normative into the descriptive in Syria’s revolution narratives, we can tackle the relationship between the ideological and the cognitive. We can also examine the relationship between the subjective and the objective: between subjective bias and objective neutrality in historical narration in general, and in the narratives related to the Syrian revolution in particular.

Doubts surrounding the objectivity of the narrative of any entity that is ideologically affiliated with the revolution are legitimate in principle. Subjectivity and ideology often constitute spokes in the wheels of cognitive objectivity. Even though such discord is possible, it is not at all necessary. In fact, in such contexts, and in human knowledge (of social and political phenomena) in general, there is no knowledge without ideology, and no objective knowledge without some level of subjectivity and bias. Subjectivity and bias are also paths to objectivity rather than possible negations of it. The same applies to neutrality, which might oppose objectivity in some cases, while it might also constitute a prerequisite to it in others. Normative neutrality between the killer and the killed, the criminal and the victim and the oppressor and the oppressed, and viewing them as mere parties, might harm the objectivity of any knowledge espousing such alleged neutrality. Such neutrality is nothing more than intentional bias, most likely siding with one party to the detriment of another.

The Syrian revolution was and still is a historical event that does not end until its outcomes, after-effects and repercussions find their closure.

Previous talk about the objectivity of knowledge or the historical narrative must not lead to believing that it is possible to achieve a complete or grand narrative entailing and transcending all other little narratives to compose a full, comprehensive one.

Such a narrative is not only impossible, but also unnecessary and actually negative because it would be closer to a grand narrative in the Lyotardian sense of the word: a unilateral narrative expressing a solitary trend refusing to engage others, rejecting all pluralism, excluding everything different, and accusing it of apostasy in addition to denying its presence or legitimacy. In that light, it is important to abandon the dream of a grand narrative, described as “the narrative of all narratives.”

It is true that the immanence and correlation of bias, subjectivity and ideology with every knowledge and narrative does not entail lack of objectivity, but this immanence or correlation clearly shows the perspective of that knowledge.

By perspective, we mean that the narrative and knowledge in general are the result of a special interaction between the self and the topic, and this interaction may vary depending on one of two aspects: the subjective interacting aspect and the objective aspect prompting the interaction.

Each piece of knowledge or historical narrative might and should attempt as much as possible to encompass the biggest number of diverse perspectives. But this attempt must be based on prior acknowledgment that the debate between different contrasting perspectives cannot reach the Hegelian structure and its related absolute knowledge. This structure is closer to a guiding light, which the researcher works hard to come close to, knowing the impossibility of such an achievement.

Syrian revolution narratives as a historiography of the past and present

There has been increasing discussion about the perspective and subjectivity of knowledge in the narratives of the Syrian revolution, as narratives for an event whose repercussions and after-effects have not yet ended, amid suffering that is alleviated at times and worsened at others. In historiography the present, legitimate and unreasonable concerns and doubts about the perspective and subjectivity of knowledge intensify.

However, the narratives of the Syrian revolution are not just historiography of the present. Ten years since the revolution erupted, it has become important to note that what many consider the present has become the past for others. Many Syrian men and women were children or teenagers when the revolution started, and they do not know much about “Assad’s Syria” and about what happened before and during the revolution. A significant number of adults did not have sufficient knowledge about the situation of their country and the nature of its political and security system when the revolution began. Syrians often justified their political distancing and ignorance of the situation in their country with their lack of interest in politics, which was not a priority for them. Political activist and media figure Luna Watfa, a former political detainee held by Assad’s regime, clarified that point in a recent article. The article notes that “even when the first protests against Assad’s regime took to the streets in March 2011,” politics was not among her priorities.

She writes that she “had no idea what she could do.” The developments pushed her to read about Syria’s political history and about the crimes of the Assad family in the country. She then understood why people were protesting in the streets” [v].

Accordingly, there is clearly an increasing need to realize that the Syrian revolution’s narratives evoke the past rather than merely document the present. Just like with any other historical process, narratives influence the past as much as they are influenced by it, and perhaps even more.

That influence on the past might be achieved through drafting parts of it in a coherent plot of its selected parts, according to a certain hierarchy of norms and knowledge-value priorities. As a result, some parts are highlighted and considered essential and important to a large extent while other smaller parts are marginalized, undermined and considered secondary.

Through looking back at the past and at history, one often falls into the trap of determinism by believing the inevitability of what happened. In one of our series’ articles, “Possible nationalism: Was the defeat of the Syrian revolution inevitable?” Mahmoud Hadhoud critically tackles this question.

‘War of documents and documentation’ and the conflict or discrepancy between Syrian revolution narratives

The war of documents and documentation between the different parties, both Syrian and non-Syrian, has been raging since the Syrian revolution broke out—a revolution in documentation as much as it was a documented revolution.

Syrian rebels insisted on documenting their revolution in ways capable of exposing the regime’s atrocities while also revealing the definition and necessity of the revolution. At the end of 2020, Time Magazine placed defected officer Caesar and film director Waed al-Khatib on its list of the 100 Most Influential People in 2020. Caesar and Khatib figured on the list because they documented events in Syria, including human rights violations in the Syrian regime’s detention centers [vi].

Director of the Commission for International Justice and Accountability Stephen Rapp said that the commission possesses more than 900,000 governmental documents showing the crimes of Assad’s regime and proving the responsibility of its senior leaders, including Assad himself [vii].

Meanwhile, the news program 60 Minutes indicated evidence of war crimes against Assad outweighing evidence against the Nazis [viii].

The conflict between narratives is part of the war of documentation. The inclusion of these documents in a narrative is perhaps the most important part of that war. Everyone who deals with narratives of the Syrian revolution is aware that each narrative is obsessed with other narratives that contradict it, and engages in an explicit or implicit debate or conflict with them.

The other narratives, be they existent or possible, are like ghosts hanging over each narrative—a ghost whose existence cannot be eliminated easily, for many reasons. For one, the ghost hangs in the middle between existence and non-existence. Besides, many forces are at play to impose a (false) narrative or narratives at the expense of one or other narratives. This conflict is a struggle over the meaning and value of the Syrian revolution, and it is part of the conflict between the Syrian revolution’s warring parties, or a continuation of that conflict, but by other means.

The cognitive and ideological difference between the narratives of the Syrian revolution does not always take that hostile form of conflict—which appears, for example, in the difference between the narratives that reduce the Syrian events to a cosmic conspiracy, and the narratives that reduce it to a revolution of good guys against bad guys.

In fact, that difference can appear between divergent cognitive visions whose owners rightly seek to present an objective account of the Syrian revolution and “constructive criticism” of some important or popular narratives.

This following series comprises texts and narratives that reflect a great amount of that disparity and those differing perspectives. The perspectives and narratives of the authors of these articles all seek what is right, as in truth and goodness, without undermining their differences. The pursuit of the truth does not necessarily lead to its attainment, and the truth, as is the case of existence, as per Aristotle, can be said in different ways.

Notes

[i] Paul Ricœur, Temps et récit, t. I. L’intrigue et le récit historique, (Paris : Éd. du Seuil, 1983), p. 69.

[ii] Jean-François Lyotard, The Postmodern Condition: A Report on Knowledge, (University of Minnesota Press, 1984).

[iii] See Housamedeen Darwich, On Revolution and Civil War in Syria, SyriaUntold, March 15, 2020.

[iv] See Nikolaos Van Dam, Destroying a Nation: The Civil War in Syria, translated by Lama Bawadi, Ahmed Bechara, Antoine Bassil and Kamal Dib. Edited by Marilyne Saade (Beirut, Jana Tamer for Studies and Publishing, 2018).

[v] Matthias Von Hein, “Luna tells her story on the sidelines of the trial of two Syrian officers in Germany,” DW website, Feb. 13, 2021

[vi] “Two Syrians on the Time Magazine’s list of 100 Most Influential People 2020,” Enab Baladi, Sept. 23, 2020.

[vii] See a video with translation subtitles from 60 Minutes show broadcast on CBS on Feb. 21, 2021 about the crimes committed in Syria, Free National Assembly website.

[viii] See: “Smuggling Documents Condemning Assad’s Regime “More than Evidence against Nazis”, Al-Hurra, Translations, Washington, Feb. 19, 2021. For the CBS report on the topic, see:

“Former prosecutor: More evidence of war crimes against Syrian President Assad than there was against Nazis”, CBS Interactive Inc. 18 February 2021.