Standing in a long queue of Syrians in front of Lebanese General Security, in the company of a mass of paper reports, orders and inquests brought in by officers wearing camouflage uniforms, I recall the sounds of bullets on the open front, the resonance of the advancing boots of Iranian militias and Lebanese Hezbollah fighters.

Young men clutch their rifles close to their chests and sing under the roar of aircrafts. The firewood smoke warms our insides from Aleppo’s freezing cold and dissipates over Suleiman al-Halabi neighborhood like a clear white cloud. We are recording the scene for a film, surrounded by the Air Force Intelligence officers positioned behind the courtyards of old houses, and the Islamic State’s masked men near the roundabout at the end of the line. I touch the dull iron of a fighter’s Kalashnikov, like a lover touching their beloved. Yes, a rifle can sometimes be a lover. If you haven’t tasted the bitterness of humiliation, you couldn’t possibly know that death is sometimes easier. It is then that the cheers of martyrdom or victory appear to be the only real thing in this life.

A world of paper

Mending what has been broken

12 February 2021

The body, between event and memory

25 January 2021

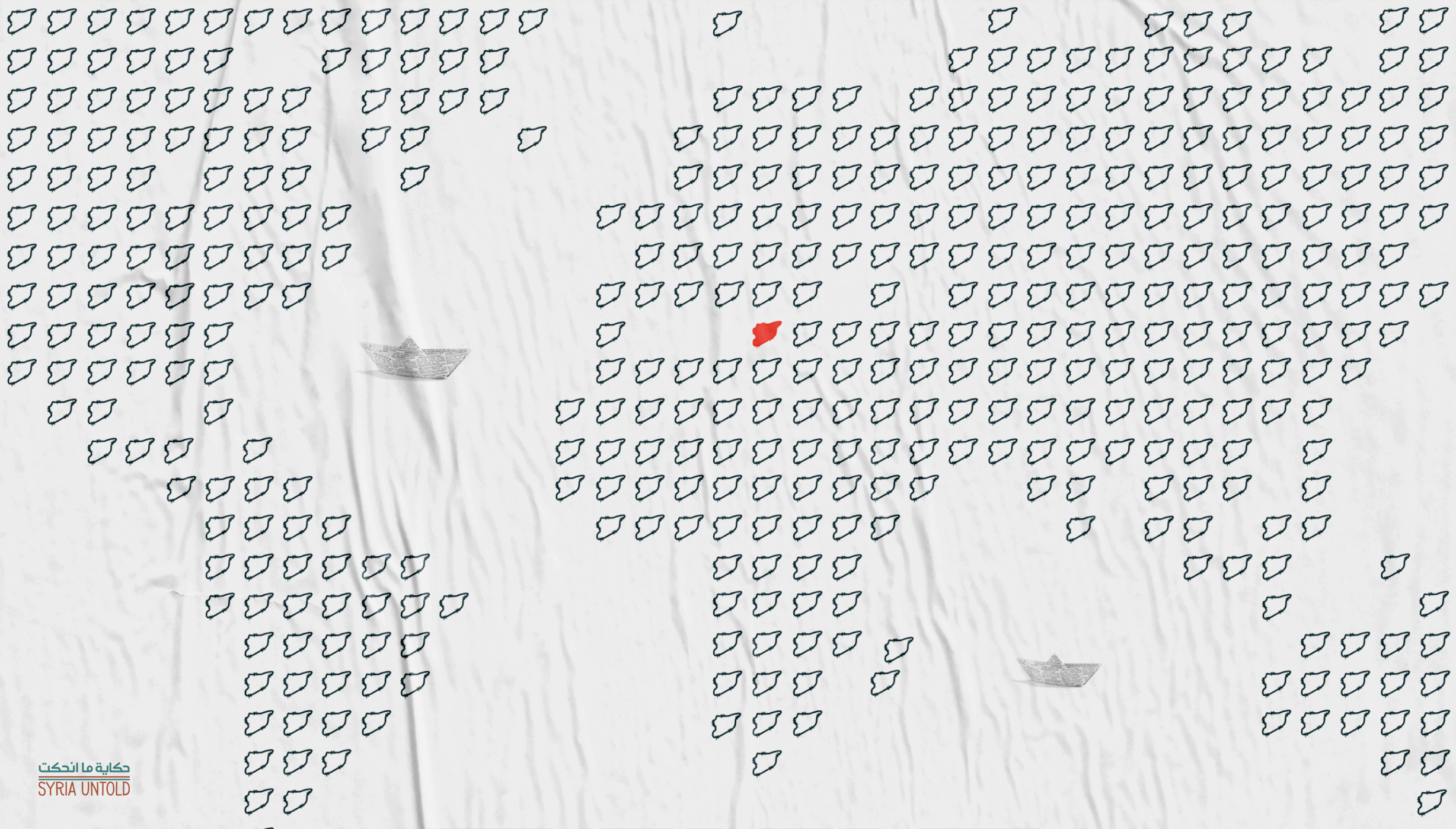

I stare around me at the tired faces concealing maps of Syrian cities in their lines. I drown in sorrow, fearing deportation. Ours is a world of paper in which trees have turned into packages containing the sorted names of people wanted by the intelligence branches. The whiteness of the papers turns into blood stains dripping onto the roots. They are cut and transformed into secret files grasped by informants, intelligence officers and the secret police in their pursuit of spoils.

A Lebanese officer looks at me: “Charges have been pressed against you.” I try to figure out what charges, but I have no way of knowing. Facing the investigation room, I close my eyes, and I hear the cries of a child wrapped in the arms of his concerned and broken mother.

The child cries bitterly from the freezing cold of Jabal al-Sheikh. The smuggler begs the woman to silence her child so that we can cross to Shebaa. Her face is drenched in darkness, and we can hear her occasional moans. In an attempt to muffle her crying, she sniffles shyly and desperately: “His father passed away and left him with me.” We nail ourselves to the ground out of fear of the checkpoints deployed in the darkness of the deep valley. Hundreds of people have fallen here before us, wounded by sniper bullets, and dozens froze to death while trudging through the piling snow. The woman holds her child close to her chest and tearfully pleads with God to guide him into silence. “Please take my life like you did his father’s, perhaps then I might find some peace.”

In Palestinian writer Ghassan Kanafani’s novel Umm Saad, the protagonist says of her son Saad, whom she encourages to become a resistance fighter: “Do you know something? Children are slavery! If I didn’t have these two children, I would have followed him [Saad]. I would have lived there with him. Tents? Well, every tent is not the same. I would have lived with them, cooked for them, done all I could for them. But children are slavery.”

I once overheard an old man in a refugee camp in Ramtha, Jordan repeating Kanafani’s words. He fell silent while smoking his Hamra cigarette, then he glared, disgusted at the dozens of young men lying down on their beds and lazily puffing at their cigarettes. They had escaped when the battles started and sat in their tents, watching the bloody clashes. The old man shouted angrily: “What are you doing here? If I were physically capable, I would have gone back and fought with them.”

“We went out to cheer that we prefer death over indignity. But, here we are, escaping death and dragging our own feet to indignity.”

In cold blood

Under the Palace of Justice, Adliyeh roundabout in Beirut, hundreds of us are led to the General Security’s Al-Jisr detention center. It resembles the prison of the Air Force Intelligence Branch under Tahrir Square in Damascus, where one could hear the cars driving by all the time with their loud humming that could drive a person mad.

In the collective prison cell no. 12, a man in his 50s tells me he was arrested in the Bekaa Valley, at a security checkpoint. The officers searched his WhatsApp messages and arrested him because of a conversation with his parents in Daraa about the wave of assassinations there. The man spent a whole month tossed about between security branches. He left behind a family of four children who had no idea what had happened to him. In Daraa, Hezbollah’s militias are desperately trying to control the area.

The undeclared war of assassinations is ravaging villages and towns that refused the presence of the party and pro-regime Iranian militias when Damascus recaptured southern Syria in 2018. The targets: anybody who has had contact with the Free Syrian Army (FSA) and rejected settlement with the regime. From destroyed houses to the border, and from the border to prison cells, and from prison cells to the world, where we beg for a semblance of a decent life in its corners; death was looming, and for that death, we cheered in protests and on the battlefronts. In fact, it is not death that scares us, but humiliation. And out of fear of humiliation, thousands marched towards their fated death.

It was just after midnight in late 2019 when members of Hezbollah and Amal Movement attacked the Ring Bridge that separates East and West Beirut. Fist fights and rounds of stone-throwing broke out on Monot Street. While escaping through the alleyways of Ashrafiyeh, I instinctively kept my head down to shield myself from stray sniper bullets.

Distorting Syria

23 July 2020

Though they had not deployed their snipers in Beirut, I remember the snipers were everywhere in Daraa al-Balad, deployed on the rooftops of houses, during the first days of the protests.

They shot at the protesters in cold blood, aiming for their eyes and mouths. At the time, we could not believe that, clad in their black uniforms, they had weaseled their way in between people’s houses. Helicopters carried them from Damascus to the municipal stadium, and from there, they entered the city in 24-passenger buses. We could not believe that sniping entertained them and that our death was a game for them. A decade on, Hezbollah’s Secretary-General admitted in a television interview that they were present in Syria since the first day the protests broke out. Meanwhile, in Lebanon, as I ran away, I could hear the cheers coming from Khandak el-Ghamik, “Shia, Shia, Shia!”

There were no sanctities in Daraa al-Balad then, and there was no holy war.

A sniper's bullet hits the eye of a child in his father's arms. The father screams in shock. He carries the child in the crossfire and shouts, “Shoot me, shoot me!” He howls at the sky, at the protesters, at justice, at freedom, but the sniper does not kill him. He leaves the man in the throes of hysteria.

October Revolution and a temporary prison

The October 17 Revolution constituted a different twist in the way the Syrian issue was handled in Lebanon. Lebanese security authorities had long intensified their crackdown and arrests, with cover from Hezbollah and through coordination with the Syrian intelligence. But the October revolution managed to shake the security hegemony of the party in Lebanon and changed its priorities. Hezbollah had invaded the Syrian border villages and uprooted thousands from their hometowns, forcing them to seek refuge in the villages of their murderers on the Lebanese side. Their lives turned into temporary prisons. The party realized that the Sunni majority who were displaced from their villages to change the area demographically were now in its stronghold. In coordination with the Syrian regime and Russia, the party increased pressure to expedite the return of refugees—a forced return for thousands of families threatened with arrest and killing. The Lebanese state, represented by the Free Patriotic Movement (FPM) a.k.a the Aounists, conducted racist campaigns to apply more pressure to further pace up the return, under the pretext of some “implosion” of the Lebanese domestic situation due to the waves of Syrian refugees.

In parallel, Lebanon’s General Security confiscated thousands of identification documents and passports belonging Syrian opposition families, women and men under various legal pretexts and issued subjugation warrants to humiliate and oppress them. The party, which felt that large areas in Lebanon had turned into a backstage for the Syrian revolution, was afraid the Lebanese revolution would benefit from the thousands of opposition-sympathetic Syrians now living in Lebanon.

Hezbollah coordinated with General Security to turn Lebanon into a temporary prison to pave the way for voluntary deportation, if the political situation in the region allowed it.

The Lebanese revolution fell into the unknown, facing increasing violence from the state, which was betting on time and the economic exhaustion of the revolution in a country already struggling with a dire economic crisis that has led it into total collapse. One question preoccupied everyone: “Now what?”

Below the window of my room that overlooked the Port of Beirut, I would hear the frightening thuds of heavy cars at dawn. I always thought they were vehicles transporting arms clandestinely to Syria. More often than not, I thought I was imagining that sound.

Flowers to the killer

At the onset of the revolution, Syrians gave roses to their killers, in the hope of convincing them that we wanted to build a nation and a country. The Lebanese also gave roses to their killers, in the hope of convincing the party that they do not want to engage in another war of elimination.

In Beirut’s Mar Mikhayel, I sat with the owner of the house where I lived for five years. During the ongoing crises that riddled the country, we developed a tight bond. His hand trembled as he extended it to me in his devastated house. We sat in the salon above the rubble. His eyes watered. He did not know what to offer me, knowing that he would rejoice each time he served me squeezed berry juice from the mountains. Holding back his sobs, he said, “I have nothing more to give you.”

That man, who had survived Lebanon’s civil war, told me: “Never in my life did I feel defeat like now. They destroyed Lebanon, just like they destroyed Syria.”

“They wanted to build an entity to push Sunnis to ally with Israel against Iran. They distracted people from all the real issues in the region. They do not want war with Israel. They only want to destroy us. If I could, I would carry a rifle and fight them. Resistance is the only solution. For a long time, we were the resistance, and we should be that resistance once again.”