This article is part of a limited series marking a decade since the start of the Syrian revolution. Read this piece, originally written in Arabic, here.

For three decades, Syrians lived under the regime of Hafez Assad (1971-2000). During that period, the right to political action and narration was limited to the official narrative of the regime alone. Satellite channels, internet and social media did not exist back then.

During the first decade of Bashar al-Assad’s rule, starting in 2000, there was nothing new under the sun, apart from some exceptions. These included what was dubbed the “Damascus Spring” (July 2000-February 2001). The Syrian revolution (March 2011) heralded a new age; and its newness was mainly manifested in allowing Syrians to express themselves for the first time in decades.

Moreover, even research studies about Syria were quite limited before the revolution because, at least at some level, it was difficult to conduct direct interviews with Syrians in the republic of silence about politics or public affairs.

Political fear constituted one of the cornerstones of the Assad family’s rule. The practice of politics was banned, as was talk about politics. The Assad regime imposed on Syrians to be citizens stripped of willpower and unqualified to take decisions or actions, which meant they had no say in their own affairs.

On narratives of the Syrian revolution

15 March 2021

The Syrian revolution and its ambiguity

17 March 2021

This context helps us understand why the conflict between the rebels and the regime since the start was not just about protests on the ground, but also about the act of narration and the account of reality relayed to Syrians in the country or to the international community. For that reason, the revolution took the form of a conflict over narratives and self-expression since its onset. It was not just a challenge to the regime’s oppression and tyranny, but also a sort of defiance to the regime’s monopolization of expression, representation and its narrative of what was happening.

The importance of narration stems from its wide role and diverse functions, as it now pertains to several fields such as literature, history, psychology, ethics and international politics (especially in wars and conflicts).

In this context, humans have come to be known as storytelling animals [i]. Apart from the multiple functions of narration, in the political field in particular, narration represents a conflict over meaning and reflects the balance of soft power.

Even hard power now lacks a narrative to gain legitimacy. Narration has also become a means to write history and retain the collective memory of a nation or certain political group, and a way to express the individual and collective identities in democratic systems. Consequently, dictatorships have constantly sought to muffle voices and monopolize the official narrative as the only true one.

Narration and the approaches of narratives

The importance of narration in global politics can be determined through three main arguments: that narratives are central to human relations as they constrain and enable behavior, that people and political actors use narratives in strategic ways, thus there is a need to understand and analyze them, and that the communication environment affects how narratives are communicated and what impacts they have. Consequently, “both the content and the form of a narrative are crucial” [ii].

Three approaches distinguish the way the Syrian revolution narratives were told:

The first approach addressed the question of how the revolution narratives were discussed on visual media. This approach did not delve into the narratives themselves, but rather into how they were expressed. For instance, in a 2017 study, researcher Rhys Crilley analyzed how the National Coalition of Syrian Revolution and Opposition Forces used Facebook. Crilley focused on the main narrative themes emerging in 1,174 posts and 528 sets of images published on the Coalition’s English language Facebook page between November 2012 and March 2015.

Narratives usually focus on both forms of speech—written and oral. But Crilley’s study analyzed posts and images to argue that the National Coalition used visual media on Facebook to project a visuality of suffering, in order to gain the support of global audiences. This type of analysis humanizes the victims of the regime’s violence—the wounded, the dead, the displaced and refugees. The victims were no longer just numbers, hence the political significance of images [iii].

Before the revolution, fear was one of the pillars of the oppressive state, but the public protests created a new experience that broke the wall of fear.

The second approach focused on Syrians’ own narratives about themselves. The revolution allowed new forms of free self-expression and encouraged millions to tell their stories for the first time. Political scientist Wendy Pearlman took notice of the importance of direct individual accounts. She studied the narratives of around 200 Syrian refugees in an intense descriptive analysis of personal interviews, concluding that individual narratives united in a collective narrative confirming the transformations that altered political fear in Syria.

Before the revolution, fear was one of the pillars of the oppressive state, but the public protests created a new experience that broke the wall of fear. With the mobilization of the revolution, fear turned into a quasi-normal way of life filled with vague concerns about a hazy future. The revolution provided a new window in building and developing the national identity of individuals.

The act of narration became an exercise of producing meaning within the revolution. Narration became in itself a revolutionary practice and political act under an oppressive regime. Even the expression of fear during the revolution constituted a political act that was not allowed in Syria before the revolution.

Political scientist Lisa Wedeen noticed that Syrians’ reiteration of regime rhetoric creates “acts of narration that are depoliticizing,” while Syrians’ telling of their personal accounts creates politicized and politicizing narratives [iv]. As Syrians narrated how they dealt with fear and challenged it, they loosened the shackles that had previously constrained their lives and made them dull and devoid of meaning. When they told their stories and participated in the events shaping their lives, they turned into political agents themselves [v].

Questions about growing change in Syrian narratives

12 January 2021

What did exile change in our narratives?

26 January 2021

Narratives of the Syrian revolution

The third approach offering a critical perspective is related to limiting the narratives and the classification of the Syrian revolution.

Various factors dictated the existence of several narratives, rather than one, for the Syrian revolution, generally because of the complexities of the Syrian situation at the levels of geography, politics, social fabric and political history.

Two elements are worth noting to help understand this narrative of pluralism. There are central narratives as opposed to sub-narratives that either branch out from the central one or serve it. It is possible to distinguish between three grand narratives.

The first narrative takes issue with the idea of the revolution for various reasons that can be grouped under three trends:

Religious: This trend does not consider the revolution a good act, because it stirs strife and can only be understood as disobedience of the ruler in the historical sense in the sultanate. Prominent figures who adopted this inclination include religious scholar Muhammad Said Ramadan al-Bouti, through his sermons and frequent television interviews during the revolution.

Modernist: This trend believes that changing society comes first, before revolting, to give the public the right to decide and elect. A revolution has certain standards based on this view. Representatives of this trend despise traditional society and label it as religious, regressive or unfit for democracy. Its espousers described the Syrian revolution as an Islamist one emerging from mosques. The main figures representing this trend include the Syrian poet Adonis, intellectual Georges Tarabichi and others.

Utilitarian: This trend encompasses diverse groups that believed the stability of the regime would guarantee their privileges, which would disappear with the regime’s disappearance. People in these groups either occupied political positions, were religiously affiliated with the regime or shared economic ties with it. This trend included the children of officials who entered the economic field, businessmen and an Alawite majority that believed the regime was its protector and an extension of it.

Syrian writer Yassin al-Haj Saleh has discussed “the existence of a new bourgeoisie” in Syria comprising the children of officials and their followers, and ideologists of modernity from the intelligentsia (like Tarabichi). This new bourgeoisie had three characteristics: ignoring the issues of moral values, neglecting social problems and having a politically conservative tendency and closeness to the regime [vi]. This applies also to the two previous trends combined.

Prior to all these groups, there was the regime and its allies. The regime was adamant since the onset about not responding to any of the demands for reform. As it had repeatedly stated, its policy was based on the option of war.

Then-Foreign Minister Walid al-Moallem said in July 2012: “There will be no dialogue before the elimination of terrorists.” By the end of August 2012, Assad followed suit, when he tied the country’s fate to that of his regime under the name of the state.

As Syrians narrated how they dealt with fear and challenged it, they loosened the shackles that had previously constrained their lives and made them dull and devoid of meaning. When they told their stories and participated in the events shaping their lives, they turned into political agents themselves.

From the perspective of the regime, war is not a political tool, but its policy to eliminate the revolution. Its aim is to annihilate the rival both politically and morally by denying their cause in general [vii]. Some studies confirmed that the regime’s destruction of cities was not a consequence of the war. Rather, it was deliberate and in line with premeditated organizational plans [viii].

The Syrian regime created counter-narratives as part of its war on the revolution to corner it since its onset. The regime propagated these counter-narratives and insisted on them internally and externally.

The regime presented multiple sub-narratives depending on the target audience and its intended goals. It claimed that the protests were demonstrations of Sunnis, armed gangs, terrorist groups and insurgents. All these sub-narratives aimed at implanting certain ideas, such as the protection of minorities in the face of a Sunni revolution, the secularism of the regime facing extremist jihadist groups, the resistance axis facing an opposition produced by imperialism and conspiring with the enemy, the violence of the revolution facing the regime’s defense of the state and nation, the treason of the revolution facing the patriotism of the regime, in addition to other narratives that evolved throughout the course of the revolution. These sub-narratives served certain ends depending on the diversity of the target audience. But they all supported the grand narrative of enmity to the revolution in principle.

To refute some of these statements, researcher Ziad Majed wrote that the regime aligned three pillars in its discourse and image construction: resistance, through which the regime won over nationalists, leftists and anti-imperialists; enmity to Islamists, which tightened his ties with some Western circles and seculars in general; and a modernist appearance that the regime reflected to show that it was ahead of its doomed people, and to satisfy superficial espousers of a so-called West or please the pretenders of progressiveness in Syria [ix].

Notably, Russia and Iran adopted the regime’s own narrative about terrorists, but the Iranian discourse specifically used the term “takfiris” which means labeling other Muslims as kafir (non-believer) and infidels.

By using “takfiris,” Iran indicated that the revolution was Sunni and that it constituted a conspiracy to strike the axis of resistance and serve Israel. Iranian Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei and some Shia clerics repeated these claims in their Friday sermons. For instance, Kazem Sadiqi in Tehran said on Dec. 14, 2018: “takfīrīs and the kufr front [disbelievers or more precisely non-Muslims] have tried to fragment Syria and Iraq and eliminate Lebanon and the resistance.” Hezbollah leader Hassan Nasrallah repeated such claims in his speeches. He said on June 8, 2018: “If Syria falls in the hands of takfiris, a disaster will befall the resistance and Palestine.”

Songs of nostalgia in New York City’s long-lost ‘Little Syria’

05 March 2021

Mourning Hassan Abbas

10 March 2021

- Pro-Revolution Narrative:

This narrative is presented by the rebels who are seeking freedom. It began as an inclusive peaceful, civil movement, then it was violently oppressed and resorted to armament to defend itself.

The revolution demanded radical reforms at the beginning, but facing the regime’s excessive use of violence and its lack of responsiveness to any reforms, the revolution’s slogan turned into calls for toppling the regime. This narrative is the one prevalent in the revolution circles in general and among several Arab and Western writers [x].

The rebels expressed their narratives in two ways:

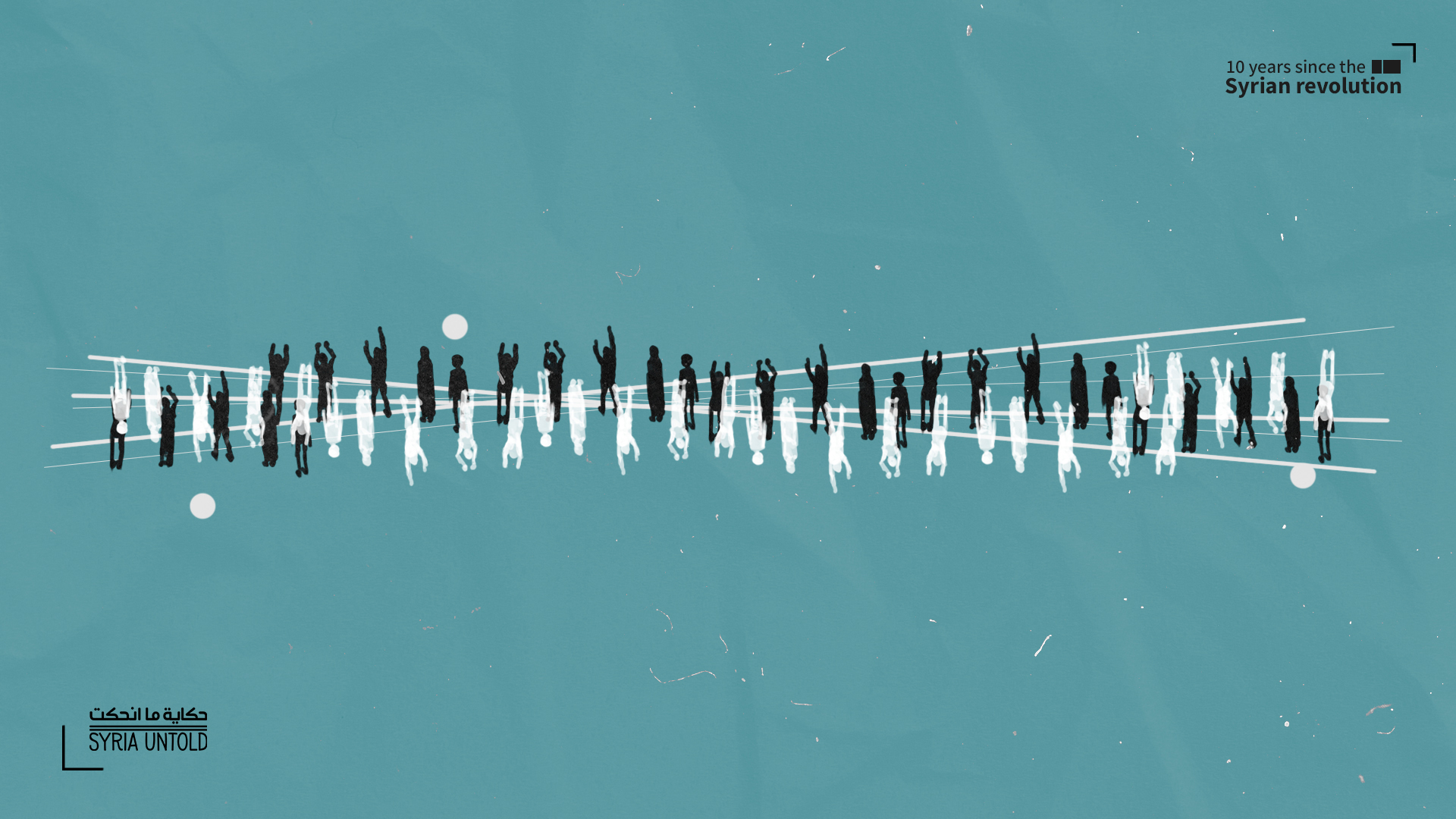

The first consisted of the act of protesting, which covered wide spaces of Syrian geography, amid the violent oppression that protesters faced during the first months of the revolution. They retained the peaceful aspect of the revolution despite the killing of several young protesters. Protesting meant risking one’s life. Still, the young rebels insistently took to the streets and voiced their disapproval and demands for freedom.

The second way entailed the slogans of the revolution, on the one hand, and the names of protests on Fridays, during which demonstrators raised banners spelling out those names. These protests expressed the united spirit of the revolution and were led by the coordination committees and the Syrian Revolution General Commission, which represented groups of young rebels on the ground and in the virtual sphere.

The slogans they repeated included “Freedom Freedom!” and “Doctor (it refers to Bashar al-Assad), your time has come!” and “The people want the fall of the regime.” Rebels in different areas shouted slogans in solidarity with the areas facing brutal oppression, along the lines of “Daraa, we are with you until death!” among others. Some slogans constituted a direct response to the regime’s decisions, like one Daraa slogan: “Oh Boutheina, Oh Shaaban, Houranis are not hungry. We want freedom.” This slogan, referencing presidential advisor Bouthaina Shaaban, came in response to the regime’s declaration, shortly after the Daraa protests, to increase the state’s public spending.

Protesting meant risking one’s life. Still, the young rebels insistently took to the streets and voiced their disapproval and demands for freedom.

The formations of the regime and its supporters used counter-slogans, the clearest and most expressive of which were “Assad or nobody” and “Assad or we burn the country.” Sectarian slogans were also invented to distort the revolution, including the ambiguous slogan “Christians to Beirut and Alawites to the grave,” though nobody knows who exactly came up with it. It was popular among groups supporting the regime both from within Syria and abroad at an early stage of the revolution. The slogan was quite clear in confirming the sectarian dimension of the revolution. The regime insisted on this issue during the first few months, and Boutheina Chaaban, Alawite advisor to the president, was the first to talk publicly about the so-called sectarian dimension of the revolution, in March 2011 and again in similar statements in September 2013.

- Analytical narrative:

While the previous two grand narratives are activism-oriented, here we are among research-based narratives, which search for the motives and causes of the revolution to present a perception of what happened. These narratives were research-oriented.

Some of them focused on the act, which was the immediate and prominent explanation, or the product of purely or predominantly economic factors. Others considered the revolution a product of social factors linked to the social changes resulting from development and internal migration.

Some narratives described the revolution as an act of sectarianism that emerged due to chronic conflicts which characterized the composition of the regime and have historical roots in the region. This was the narrative that the regime promoted and some Western researchers agreed with.

The regime strongly sought to sectarianize the revolution to achieve several goals: activating sectarian fanaticism internally, winning over minorities under the pretext that it is their sole mouthpiece and protector in the face of a frightening Sunni majority revolution and ensuring international support against the protests. Therefore, the opposition is often asked about its plan of action regarding the Alawites and other minorities, especially since the composition of the regime and its military and security institutions are based on sectarian considerations.

The economic perspective adopted by a number of Western researchers also revolved around the effects of the economic liberalization approach taken by the Assad regime; thus, the revolution was a revolution of the poor and marginalized.

Researcher Jamal Barout combined the economic and social factors by studying the relationship between development and social change in Syria in the first decade of the 2000s, to understand the dynamics of the so-called “protests.” He concluded that it was a “revolution of local societies,” meaning the revolution of middle-sized and small cities, and popular neighborhoods and slums in other cities. It was, at the center, represented by Damascus and Aleppo, and it was brought about by a pairing of the authoritarian regime and economic liberalism [xi].

If the first and second narratives were involved in the conflict between the regime and the rebels, then the third narrative is that of researchers and observers above all, despite the possible sympathies that some of them might feel for one of the parties. The advantage of this three-way classification of narratives—anti-revolution, pro-revolution, and the analytical narrative—is that it achieves the feature of inclusion first and helps us not to confuse narratives between what is central, and what is secondary and serves the central. It also helps us differentiate between narratives of the actors and those of observers. I distinguish here between narration and analysis or interpretation. Narration examines self-expression, motives and fears of the actors themselves because it expresses individual or group identities. The Assad regime is aware of itself only through its sectarian identity.

In contrast, explanation explores the factors composing the phenomenon or event separate from it. Some wrote about the revolution while they were involved in it in some way, combining the novel with the revolutionary practice or their support for the revolution. Their narratives fall within the revolutionary act itself, as I explained before, which distinguishes them from the pure research act in which the researcher and his subject are two separate entities.

In fact, we find that the revolution is a complex act that includes several factors: the first is the geography in which the event takes place—cities, areas and protest squares. The second is represented by the traits of the actors and their affiliations, be they religious, intellectual, geographical, social or economic. The third is the means of self-expression or protest, which vary and take different forms, whether traditional or modern—social media, mass demonstrations, mobile demonstrations, naming gatherings and protests, media coverage and narration itself. The fourth factor is the interactive nature of the revolutionary act and the political act in general. The revolution is not a single act; rather, it is continuous and action-generating, the product of previous events.

The problem arises when we present an oversimplified analytical vision of a complex action that includes the previous factors, and that amassed more people due to the course of events and the popular mobilization. Since the start, the regime was keen to extinguish the revolution and prevent it from turning into mass popular protests. It did this by controlling the sheikhs and mosque preachers and warning them of “provocative sermons.” The regime’s brutal violence and arrogance in not responding to any real demands for reform drove the demonstrators to despair. Protesters called for toppling the regime, and this gave the revolution more momentum in a generally revolutionary Arab environment, amid the revolutions of Tunisia, Egypt, Libya and Yemen.

While the first and second narratives had a normative evaluative meaning, this was not the case for the third narrative, which either sought to understand and explain for research purposes rather than give recommendations to the decision-makers, or to determine responsibilities and point the finger of blame. However, some of these analytical narratives made the same mistakes of the repressive regime that muzzled people’s mouths for decades, when they mentioned hidden or esoteric motives of the protesters instead of relying on the narratives of the actors themselves.

After all, narration is a political and revolutionary act that expresses emancipation from the oppression of the regime of fear after decades of silence. Here lies the importance of personal interviews or observation of the language of symbols and slogans raised by the demonstrations, which constitute a discourse.

One must steer clear of projection or imposition of dry, incomplete or esoteric analysis of an unprecedented act of liberation that was buried with brutality. This violence engendered an enormous degree of human and material cost unseen in modern history.

Notes:

- See: Jonathan Gottschall, The Storytelling Animal: How Stories Make Us Human, Boston, New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2013.

- See: Crilley, Rhys. Seeing Syria: The Visual Politics of the National Coalition of Syrian Revolution and Opposition Forces on Facebook, Middle East Journal of Culture and Communication 10 (2017) 135; Bruner, Jerome. The Narrative Construction of Reality. Critical Inquiry, 18 (1991) (1): pp. 1–21; Somers, Margaret. The Narrative Constitution of Identity: A Relational and Network Approach. Theory and Society, 23 (1994) (5): pp. 605–649.

- Crilley, Rhys. 133–158.

- Wedeen, Lisa. “Acting ‘As If’: Symbolic Politics and Social Control in Syria.” Comparative Studies in Society and History 40 (1998) (3): 522.

- Pearlman, Wendy. Narratives of Fear in Syria, American Political Science Association, 14 (2016) (1): 31-32.

- الحاج صالح، ياسين. الثورة المستحيلة: الثورة، الحرب الأهلية والحرب العامة في سورية، عمان: المؤسسة العربية للدراسات والنشر، 2017، ص120.

- Idem, page 89.

- Vignal, Leïla. Destruction-in-Progress: Revolution, Repression and War Planning in Syria (2011 Onwards), Built Environment, 40 (2014) (3), 326-341.

- ماجد، زياد، سوريا الثورة اليتيمة، بيروت: شرق الكتاب، 2013.

- See, for example:

بشارة، عزمي. سورية: درب الآلام نحو الحرية، محاولة في التاريخ الراهن، الدوحة: المركز العربي للأبحاث، 2013

Yassin-Kassab, Robin. Al-Shami, Leila, Burning Country: Syrians in Revolution and War, Pluto Press, 2016; Provence, Michael. Unraveling the Syrian revolution Author, Regions & Cohesion, 2 (2012) (3), Special Issue: A changing of seasons? The Arab Spring revolts and past uprisings, 153-165.

- See:

باروت، محمد جمال، السلفية الشعبوية في سورية و«ثورة المجتمعات المحلية» - محمد جمال باروت، صحيفة الحياة، 17 نوفمبر، 2011؛ وباروت، محمد جمال، العقد الأخير في تاريخ سوريّة: جدليّة الجمود والإصلاح، الدوحة: المركز العربي للأبحاث، 2012.