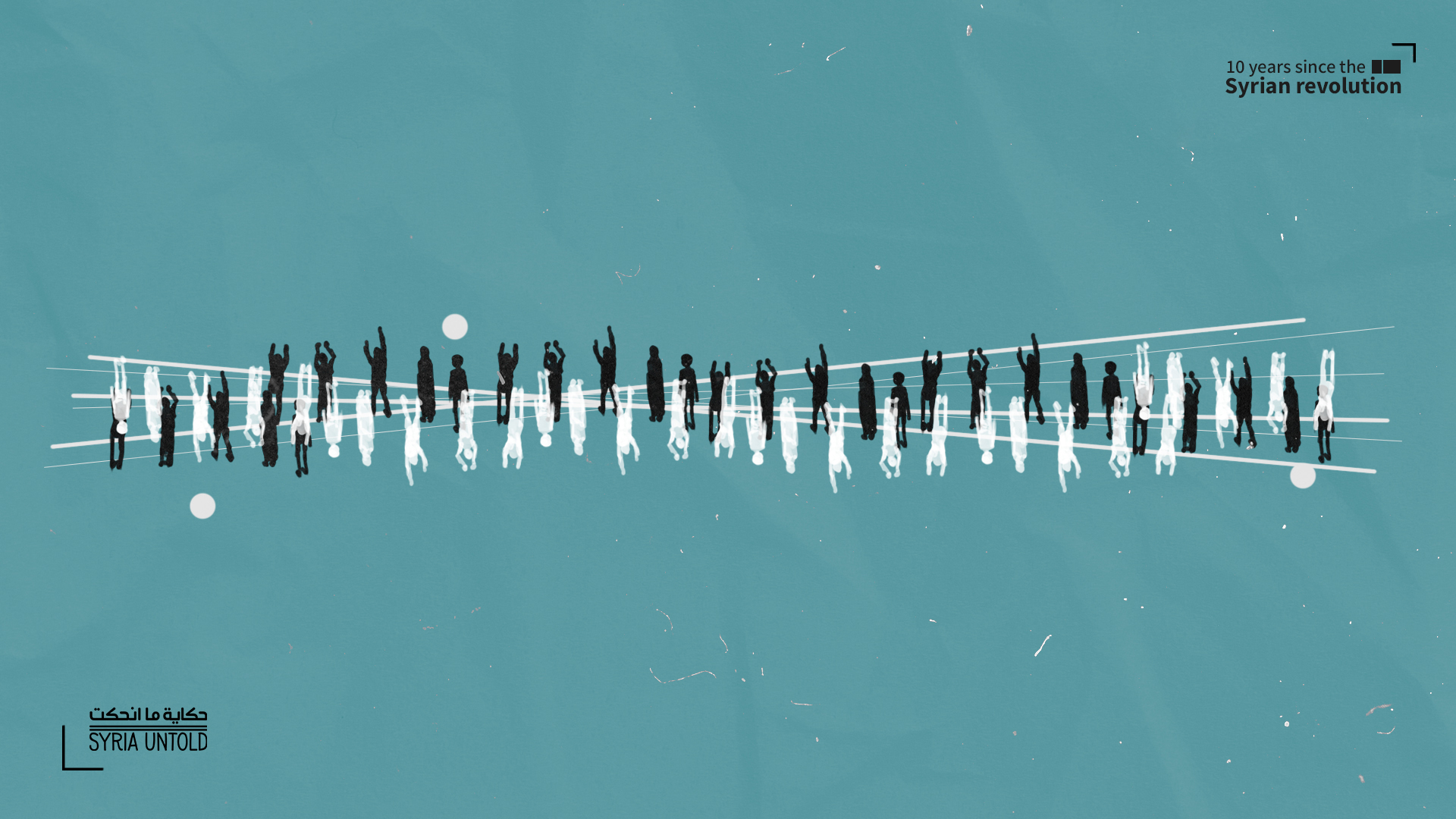

This article is part of a limited series marking a decade since the start of the Syrian revolution. Read this piece, originally written in Arabic, here.

Edward Said gave the term “narrative” one of its clearest definitions: “a version of history.”

A narrative is therefore a great responsibility—one requiring tools, time, standards and an open text without limits. This article aims to offer a preliminary approach to the different narratives that have circulated about recent events in Syria. I also offer my view on the “explosion” since March 2011. This piece involves an analytical aspect that is open to criticism, revision and proof. Yet historical narratives should rely primarily on accurate and timely information.

Throughout the past decade, many narratives were developed to explain the explosion of the situation in Syria. Many elements affected these narratives, and, despite the fact that many of them were impacted by different factors, and many scenarios were ruled out for rational reasons, agreeing on a general and objective narrative today is akin to a dream. There are great discrepancies in perceptions. One person's view could change each second because of the complexity of reality and its great interconnectedness, which goes beyond the individual interests of different people and collectives.

On narratives of the Syrian revolution

15 March 2021

The Syrian revolution and its ambiguity

17 March 2021

Common trends govern the narratives and readings of current events and history, but many of them fail when cross-checked against known intuitive facts. They also fail to achieve methodological coherence or connect backgrounds with results. They give no additional insights in understanding reality and predicting future steps and outcomes.

Building an objective narrative and accurately interpreting events, trends, and policies, require a number of essential tools, without which one cannot establish an objective approach. In fact, a misreading could contribute to intentionally or unintentionally misleading narratives for both the individual and others.

A solution could be for each individual to present their own narrative, one that is the closest to truth. It is important to bear in mind that a narrative's significance at the end of the day is not just in its personal value and reasoning; it is in its interactions with the developments on the ground. Current and future outcomes affect narratives through modification and contextualization. History itself is often rewritten based on the changes in present situations, the balance of power, and outcomes.

Before addressing commonly shared narratives, it is important to point out some ideas. First, no narrative could capture the entire reality. Some elements and details will certainly remain missing.

Second, the narrative told during an event, especially when the one telling it is part of the event, will differ from the narrative one would adopt or reach after the event. The Syrian explosion has not ended for one to say that the narratives are not influenced by ongoing developments, ideology, belonging or prior political positions. However, this realization should not lead one to passiveness or diluting clear causes, as this pushes one to a place where they are unable to affirm anything or adopt any version of truth.

Third, narratives will definitely be influenced by the author's positioning as victor or loser. In 1789, some denied and rejected the French Revolution. If, back then, the revolution had not won, the vision of the deniers would have prevailed today. Some narratives change in line with the shifts in the balance of power on the ground and the outcomes. This is what happened in the past and still happens today.

Narratives of the elite and narratives of people

Public opinion is not the only determinant of politics. Politicians and intellectuals could greatly disagree on the average person's narrative, which is often naturally influenced by the latter's concerns about non-contested issues directly affecting them.

Meanwhile, the political and intellectual elite link the current moment to the strategic scene, and the present to history. They connect temporary individual interests with the greater national interest. This is how it should be.

What is the use of politicians and intellectuals if they are only there to repeat the slogans of the people without any modification, development or contextualization? Most people praised Bouazizi at first, but some soon started cursing his name, which only meant that they had hit a dead end. Some used to glorify figures of the Syrian opposition but soon started mocking them. The revolution highly regarded defectors from the Syrian army at first, but they soon started viewing them as products of the Syrian regime's schooling and upbringing.

What is the use of politicians and intellectuals if they are only there to repeat the slogans of the people without any modification, development or contextualization?

In Syria, we faced a great problem at that level. Some politicians and intellectuals fell into the trap of being influenced by the average person's narrative, repeating it or implementing it. Others adopted narratives that benefitted from people's temporary feelings, instincts and aspirations.

When the narratives of the political and intellectual elite become the exact same as those of the average person, it is a troubling sign. A number of popular and irrational scenarios spread among the Syrian people or were leaked to them through the regime, other countries, satellite channels, or intelligence agencies. Together with other factors, namely the violence of the Syrian regime, these narratives created many developments and changes that affected the overall Syrian scene and brought it to its current state.

Subjective or missing narratives

Several common narratives and their backgrounds could be briefly presented. Each of them nevertheless requires rigorous research to fact-check and compare to facts and evidence. It is also necessary to critique and deconstruct the narrative itself to reveal its gaps, contradictions, and dichotomies.

The body, between event and memory

25 January 2021

Murder, and the burden of proof

06 January 2021

In my opinion, the regime's narrative could not be logically justified. The regime insists that what happened in Syria was a foreign imperialist, Zionist and regressive conspiracy intended to weaken the resistance axis. Still, some people adopted and believed this narrative. One cannot state that all those who supported the regime's narrative did it for personal gains or sectarian considerations, because some actually acted in accordance with their beliefs while others simply adopted this narrative for different reasons.

Some narratives were designed and circulated for populist reasons. Those narratives soon became effective and kept on gathering supporters who would adopt and defend them. For example, in the first month of the revolution, the regime warned against a threat of Islamization and sectarianism. The regime used this narrative before there was any sign of such a development, and justified it. The regime would say that it knows more about Syrian society and the lack of cohesion and effective political power it suffers from. The regime also knows what it has produced over half a century of political domination. Second, there was a similar Syrian experience in the1980s and other experiences in neighboring countries that make this narrative more believable and ultimately true. Third, the lack of national cohesion painted a grim picture for minorities locally and abroad, which helped the regime gather support locally and relieve potential international pressure.

Another narrative views the explosion of the Syrian situation as a revolution of the Sunni majority against the Alawite leadership, in an attempt to establish an Islamic state. This narrative also does not stand in light of the many scenes and experiences of the first year, the slogans raised, or the diversity of groups present at the time. It also does not stand when one makes a count of the Sunni Muslims who supported the regime for different reasons, and of those who did not care about the events altogether.

There are narratives that relied on a sectarian view or position in reading the political scene. For example, some common narratives relied on a sectarian rationale to explain events through the policies and practices of Iran, Hezbollah, Saudi Arabia, Qatar, Turkey and other countries. The narratives overlap in some ways with the sectarian background of the speaker and the subject being interpreted. They are confusing and do not lead to any objective reading or understanding of the politics at play. Different countries and forces could use the sectarian narrative to divert attention, gather support, and muster armies. However, in most cases, there is not a link to religions or sects. The different ideological narratives are still present in the approaches to the Syrian issue.

Ideology and its preconceptions often take over people's minds and hearts, and they stand in the way of them providing an objective narrative of reality. Their main concern is proving that reality and developments are going in line with ideological principles and that they have always been right. There are unlimited examples of this type of narrative and analysis. Some Arab communists, for example, find it difficult to understand the Russian role, which conflicts with the aspirations of people in the region. At the same time, Kurdish nationalists can only address Turkish politics with hostility and suspicion. As for Arab nationalists, their narratives diverged with Abdel Nasser's Egypt.

Different countries and forces could use the sectarian narrative to divert attention, gather support, and muster armies.

Some narratives were built around the media statements of decision-makers and the media monitoring of specific, non-comprehensive, biased, or dishonest sources broadcast through satellite channels.

Rights-based narratives were also present, and their readings were from a human rights angle, not from the angle of political interests and the balance of power. This view considers rights to be the motor of reality and the source of policies. The rights-based narrative thus operates with the certainty of justice and rights prevailing in the face of oppression, and it has built roadmaps that are detached from the reality on the ground and its developments.

There are also personal narratives which read reality based on individual goals and interests. These readings impose personal hopes and interests on reality. Reality in this case becomes a factor of personal hopes, whims and considerations. One form of analysis starts with understanding incidents and reality starting from a specific political position without a clear distinction between the position and the analysis. The position therefore masks the analysis. For example, a supporter of the regime would read the Syrian scene differently in comparison with a supporter of the opposition. This would qualify as a personal reading, which cannot assess reality or events outside the personal political position of the viewer.

Other narratives understand ties between nations as simple and linear, and divide countries and forces along fixed axes. Some nations were seen as absolute enemies, others as absolute friends, and within each axis, ties are viewed as unidirectional and unchanging. From this perspective, incidents on the ground were explained and narratives drawn based on this misleading oversimplification. An example is the assumption that Russia, Iran and the Syrian regime are perfectly aligned. Meanwhile, the reality shows the presence of complex ideological, economic and political contradictions among the different allies, in addition to the points of agreement.

In several narratives, other experiences were evoked from history or modern times, and they were pasted to another context—our own—without depth of analysis and contextualization. Those narratives did not account for the current experience, the details, the conditions, the timing or the actors at play.

A famine, a ship and a folk song that spanned borders

18 December 2020

Sudan: no longer a visa-free haven for Syrians

15 January 2021

For example, members of the Syrian opposition copied perceptions from the Libyan experience. They constructed a narrative and squeezed the Syrians and Syrian reality into it. They made predictions based on what happened in Libya from military intervention to the political bodies that accompanied it, like the creation of a National Transitional Council. This narrative soon became valid, given the forces and personalities that adopted it and relied on it.

Finally, an economic narrative emerged through some researchers. They saw that the Syrian explosion resulted from a social problem and an imbalance in the division of wealth. It was thus the result of the liberalization of the economy, which brought higher poverty rates and the impoverishment of rural areas. Those areas ultimately rebelled.

This analysis is correct and useful, but it does not explain the total explosion of the Syrian context. In fact, the economic downturn was not the determining factor, because the Syrian economy has always been in crisis. An explosion could not have happened without the revolution happening in Tunisia and Egypt, on the one hand, and the degrading treatment of Syrians in Daraa and other regions, on the other. The incidents of murder, arrest, and torture at the hands of security officials aggravated the situation. One cannot say that the revolution could only be observed in rural areas. In fact, all Syrian cities witnessed protests, except for the centers of Damascus and Aleppo, partly because both centers were trapped by the regime. There were also invisible borders governing the social, architectural and mundane realities that separate the city and the countryside in most Syrian regions.

My own narrative

In the past section, I used the term "Syrian explosion" because I was trying to keep my narrative separate when discussing others. The explosion in Syria started with peaceful protests. The regime relied on policies of violence, murder, detention, torture and degradation, pushing all cities to rebel. Many elements of Syrian society participated in the revolution and were civilized in expressing demands with national dimensions.

No party or state could deny the validity and fairness of the demands the protestors were calling for in March 2011. It would be difficult to prove that those protests were not generally peaceful in the first year. It would equally be hard to deny the nature of the demands back then, which were based on Syrians united for freedom and dignity. The slogans called for a transition from a country run by one family to a country belonging to all Syrians, with a democratic change of power and a fair distribution of wealth. Throughout 2011, this was the dominant picture.

Afterwards, new factors and gradual changes led to predictable shifts, with the regime’s increased violence at the center. The international community, meanwhile, hesitated in taking any steps. Instead, they adopted the position of the observer, to maintain their own interests or avoid possible repercussions, given the opposition's political weaknesses. The struggle gradually changed, and new forces appeared and exploited the vertical division in Syrian society. Regional and international interventions invested in this division and the same parties.

The explosion in Syria started with peaceful protests. The regime relied on policies of violence, murder, detention, torture and degradation, pushing all cities to rebel.

The current Syrian situation has a bit of everything. It is a revolution woven into a civil war with notes of a crisis and an extension of a regional and international struggle on Syrian territory. The reality is intertwined and highly complex. The worst part is that, today, instead of Syrians presenting themselves as Syrians first and foremost, they have been sucked into ethnic and sectarian struggle along with militias of other countries fighting on their own land.

We are faced today with a general failure: the failure of the forces of the revolution, the failure of political opposition, the failure of the system and the failure of the great regional powers in producing a solution that would usher Syrians into a national, democratic, modern, secure and stable state. The explosion continues, and one cannot deny the possibility of its evolving in the future towards a clear and final end. Such a conclusion would put the past behind us and open the possibility for building a Syrian public sphere that would isolate the current actors and build a democratic state. When that happens, the Syrian explosion would go down in history as a progressive revolution. Anything else would be the start of the disintegration of Syria and the Syrians.

When some ask whether what happened was a revolution it is often against a backdrop of a positivist and moral evaluation of the definition of a revolution. Then, the actions are approached from a strictly moral angle which only looks at the mistakes of the revolution. This leads to a denial of the positive meaning of the Syrian revolution and reducing it to its mistakes.

This approach is wrong. The mistakes of any revolution do not solely result from the mistakes of its members—they also reflect the nature of the system that revolution is rebelling against. The more brutal the system, the greater the mistakes of those who rebel against it. By being the strongest actor on the ground, the regime largely dictates the rules of the game.

The desirable grand narrative: The national narrative

The desirable narrative is the one that is not produced by our personal views or our political bias. Rather, it is the narrative that is governed by the logic of history, its rational approach and a view of the developments, changes and outcomes. History does not care about our personal narratives. It might accept them at first, but it always remodels them until they are closer to objectivity and comply with the laws that govern and control.

The problem today is aggravated due to the absence of a national narrative. This does not mean that we are aiming for a single narrative to summarize the Syrian developments. We are instead aiming for a narrative that would develop in a democratic environment of recovery. It would likely be a synthesis or a revision of all the narratives, their interactions and the deconstruction of some of them. It would be a narrative that has been willingly and gradually developed through dialogue. Such a narrative could build collective awareness and the story of a people.

A national narrative of the Syrian explosion and its aftermath cannot be developed without a national, democratic state and a peaceful and safe environment. With such a narrative, we would be looking at a culturally new Syria, as each narrative includes a vision of the self and the other. Syrians would view themselves as a people and a nation in the future, and express their vision of their surroundings and their global positioning.

Today, many people doubt ideas, aims and grand narratives because knowledge lies in information produced by technology, not narratives. It relies on a pragmatic approach that does not need great goals to establish legitimacy and credibility. In this system, small narratives mask the greater narrative. This might have been true in a world that has already produced its grand narratives, but for us, building a grand narrative could help us continue to affirm our destiny and existence in the present and the future.