Western travellers encountered Palmyra’s ancient ruins, situated in what is now the eastern desert region of Syria, in the 1700s. By the following century, photos had begun to circulate of the remote site, and archaeological excavations began.

Outside Syria, the site's ancient columns, looted treasures and crumbling stone walls became the stuff of exoticized fantasies about long-ago desert empires. Buses toted tourists more than 200 kilometers across eastern Syria to snap photos of what remained of the city once ruled by the oft-romanticized Queen Zenobia.

But all of that was before Syria’s war. In May 2015, Islamic State fighters captured and occupied the historic site, as part of a broader military campaign to seize territory across eastern Syria and northern Iraq. Soon, the group began publishing images of their deliberate and spectacular destruction of some of Palmyra’s most important monuments, including blowing up one of its ancient temples.

The destruction sparked a great international uproar, covered widely by international media. For once, the world appeared united when it came to Syria—this time to mourn the global loss of an extraordinary piece of historical heritage, and to condemn the barbarism of the Islamic State.

And yet, these expressions of international solidarity took place while thousands of Syrians were dying, massacred mainly at the hands of the Syrian government, rather than the Islamic State, however cruel and violent it was.

Such international sympathy never seemed quite as potent towards the tens of thousands of Syrian dead, displaced, wounded and detained, as it was towards these wonderful yet inanimate carved stones left detonated and demolished.

Nearly six years since the destruction at Palmyra, and a decade into the war that has torn Syria apart, few events have revealed so powerfully and clearly the profound distance of perceptions between Syrians and the rest of the world, when it comes to examining all that happened after 2011. We remember many Syrians shocked and disturbed by a reality that was quickly becoming clear: destruction of monuments garnered more attention (and sympathy) than their own lives and the lives of their loved ones.

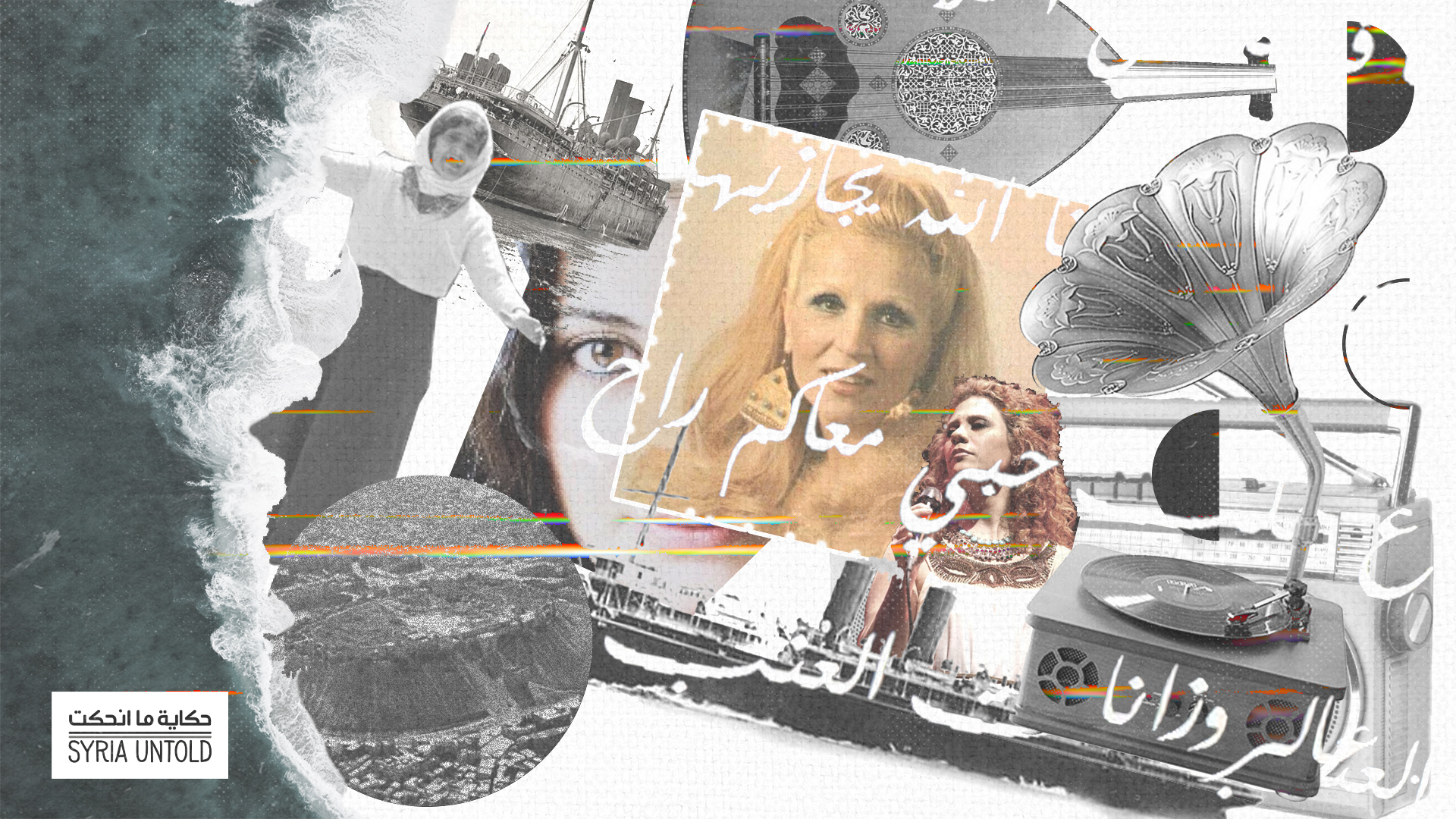

A famine, a ship and a folk song that spanned borders

18 December 2020

This distance fit into existing Western-centric and Orientalist views towards Syria and the Middle East in general.

For much of the world, Palmyra had long been associated primarily as an exotic tourist site. Its monuments preserved the memory of Zenobia, who tried to resist the Roman Empire, later punished for her efforts by forced exile. Her fate is a reminder of the power of Rome.

But for many Syrians, Palmyra connects to another time and an altogether different historical context.

The city’s name in Arabic is Tadmur, a name that also lends itself to one of Syria’s cruelest prisons, located just a few minutes’ drive north of the ancient ruins, in the modern town of Tadmur.

Closed 20 years ago, though reopened briefly during the Syrian civil war, Tadmur prison was for decades synonymous with the torture, ill treatment and outright massacres carried out within its walls. Most notably, on June 27th 1980, a group Syrian soldiers sent in by Rifaat al-Assad killed somewhere around 1,000 political prisoners after the Muslim Brotherhood’s attempt to kill his brother, Hafez.

In his introduction to our file on queerness and the Syrian revolution, activist and researcher Fadi Saleh recalls how LGBTIQ Syrians’ demands to be included in the agenda were often waved away with the justification that “your time is not now.”

Of course, many non-Syrians would not know that ancient Palmyra—designated a World Heritage Site by UNESCO mere months after the June 1980 massacre—is located steps from the prison, nor would they have heard about the fates of the political prisoners sent there.

But this disconnect is not where we wish to focus the remainder of our article.

The cultural clash in the aftermath of Palmyra’s 2015 destruction not only revealed the Western-centric outlook of many foreign Syria observers, but it also, perhaps more quietly, shed light on an important yet neglected question: which topics can be legitimately debated in an environment where human beings are being killed, dispossessed and displaced?

Can such conversations give room for Syrians to discuss the destruction of Palmyra’s monuments, from their own point of view?

A Syrian visiting a Nazi camp

25 September 2019

These questions are not limited to historical heritage or monuments, but should be extended to other issues, such climate change, the impact of the war on Syria's fauna and forests, and a myriad of cultural and social topics.

The answers are less simple than they may appear. For non-profit organizations, including SyriaUntold, which mainly relies on NGOs in order to produce content, it is not easy to find funding to cover certain issues, such as the environment. Sometimes such proposals are turned away with answers such as: “We are not sure Syrians would be interested” or “Could you instead give us a proposal on human rights, or more political issues?”

This frequent rejection, when it comes to engagement with certain issues, exposes an opposite but equally problematic and Orientalist position: Syrians (and perhaps Arabs in general) are entitled to speak only when it comes to politics, war and human rights. They are often confined to the role of eyewitnesses and are fetishized as local storytellers. Often, they are accepted as contributors to the debate only when it comes to “their” topics—war and politics—and not others, such as environmental change, visions of the future or global policy.

We can call this cultural paradox the “Palmyra syndrome,” a phenomenon that extends to a myriad of topics. In his introduction to our file on queerness and the Syrian revolution, activist and researcher Fadi Saleh recalls how LGBTIQ Syrians’ demands to be included in the agenda were often waved away with the justification that “your time is not now.”

Syrians should reclaim their right to speak about these issues—including, perhaps, the importance of their cultural heritage—and should do so on their own terms, not leaving these conversations to people who would approach them through inevitably foreign, and often Orientalist, lenses.

This means to start up these conversations in a way that recognizes the place of these issues vis-à-vis other, more relevant ones. Is it possible to talk about environmental issues in Syria and their effects on the lives of ordinary people, while not ignoring the fact that human rights, oppression, killing and displacement should always have the priority? And if the answer is yes, how can we raise these conversations an ethical, relevant way?

These questions are all difficult to answer, and the debate is open. After a decade of revolution, war and displacement in Syria, the paradox should be discussed, and Syrians should reclaim the right to talk about what they themselves consider relevant.