My father, Ahmad Adib Shaar, died suddenly in California in 2018. He had left Syria for the last time four years earlier, via Turkey. I hadn’t seen him since 2014, but he left behind a book manuscript in Arabic on Aleppo folk traditions, a trove of rituals collected from the city’s long history.

In his book, my father catalogued the observations he made throughout his life in Aleppo’s Old City, and narratives he gathered over the last 25 years before his passing. The traditions he documented primarily reflect life in Aleppo throughout the 20th century, particularly around his birth year, 1950. My father was a board member of Aleppo’s oldest cultural heritage group, al-Adeyat Society (founded in 1924). Long before leaving Syria, he presented snippets of his book-in-progress as talks at the society and other groups. With the boom of Facebook in Syria from 2009, he published some of these future book passages as timeline posts, garnering attention from people across Aleppo.

I am one of a few family members and friends of my father now editing his book to prepare it for publication. As I make my way through his writing, one of the traditions he described stopped me.

Mothers in Aleppo had a spell to unleash the voices of children suffering from alalia—speech delay. As my father wrote:

Syria’s lucrative detainment market: How Damascus exploits detainees’ families for money

13 April 2021

Mending what has been broken

12 February 2021

“If the child’s speech is delayed, his mother takes him to one of the gatekeepers of the Umayyad Mosque, who keeps a copy of the key to the...shrine of Saint Zachariah. For a very small fee, he inserts the key into the child’s mouth and turns it as if to open the door of the shrine, claiming to unleash his tongue (يطلق لسانه). An alternative solution is performed by an older brother or relative whom the mother sends to the neighborhood mosque, along with some treats and desserts. The teenage relative sits at the door of the mosque, putting the treats in the tail of his gallabiyyeh dress, and tying the child’s big toes together with a thread. When worshippers start to come out of the mosque, he repeats, referring to the speechless child, ‘untie his knot and take your lot.’ The first person to untie the thread takes the treats, in the hope that the child will soon start to speak.”

Today, there are hundreds of thousands of Syrians locked away in government prisons, whose voices haven’t been heard in nearly a decade. Syrian and international organizations have done the impressive feat of counting and documenting names of the disappeared. Several ranking government officials have been tried abroad in person or in absentia. But nothing seems to put enough pressure or incentive on the government to secure the lost freedom of Syria’s detainees. Maybe we can adapt one of the two rituals mentioned in my father’s book to free them. But, locked away in the government’s vast underground network of detention facilities, they are difficult to bring back. Oftentimes even their whereabouts, or information on whether they are alive or dead, remain hidden.

Since 2011 alone, over 100,000 Syrians have been detained and disappeared, the vast majority by the Assad regime. Tens of thousands of them have been tortured to death or executed in secret police dungeons across the country or in the cells of notorious military prisons such as Saydnaya, where many of those who do survive torture face execution following secret summary trials.

Outside prisons, Syrians are not free either. For a brief moment, the 2011 uprising ended decades of stifled speech. But Syrians have paid a harsh price for rising up, and remain imprisoned by fear for their loved ones and uncertainty about the fate of both themselves and the country. They are muzzled by a mafia—one which knows that only a monopoly on Syria’s political sphere can guarantee its continuity.

When worshippers start to come out of the mosque, he repeats, referring to the speechless child, "untie his knot and take your lot." The first person to untie the thread takes the treats, in the hope that the child will soon start to speak.

In 2011, Syrians had hope—at least for some months—that they would become free, if not on their own, then once the world embraced their struggle. Instead, the world’s reaction was divided between continued support for the regime, opportunism, indifference and, at best, a pretense of incomprehension. Or could it merely have been inattention?

Writing and talking about the Syrian plight is not enough. We need more direct, personal interaction. We can’t know how effective it was in the past to unleash children’s delayed speech by unlocking their mouths with keys, or by untying knotted toes in exchange for sweets. But given that all else has failed, what do we have to lose in trying the same for Syria’s detainees and disappeared?

Long night to resurrection

05 February 2021

Syrians who don’t live under the direct noose of the Syrian government or who have not been afraid to speak up from abroad could adopt some variation of the following: have sit-ins or public demonstrations as individuals or groups of two or more. Each participant could represent a specific detainee or all detainees in Syria. Where should it be done? The country doesn’t matter, nor does the venue, but if we are to learn from our forebears, we should do it in places of large congregations or cultural significance, from places of worship to universities, opera houses and concert halls.

To stay as faithful to the original ritual as possible: in Germany fill a basket with Pick Up! or Milka chocolates and some Haribo gummy bears, or get some Syrian Derby chips and date-filled maamoul cookies from Arab supermarkets along Sonnenallee in Berlin; in Hungary, where I lived for several years, there is the Balaton wafer or Túró Rudi. Or just Oreos, Mars, Twix, Snickers.

Tie your big toes with a shoelace. In keeping with the shouts of the teenage relative in that long-ago Aleppo ritual, shout one of the slogans that might best express why you’re giving out candy to strangers in the first place:

Untie their knot and take your lot

Set them free and take your fee

Set them free and take this treat

And then engage in conversation about Syria’s detainees with curious passers-by. Have someone take photos and share them.

I initially wrote this article in 2019, before the outbreak of COVID-19. Detainees worldwide now find themselves in a more vulnerable position. Those in Syria are enduring especially difficult conditions because of torture, intentional denial of medical care and overcrowding.

In 2011, Syrians had hope—at least for some months—that they would become free, if not on their own, then once the world embraced their struggle.

Outside prisons, we now have to observe rules of physical distancing. That said, we cannot wait until the pandemic blows over to take action. The unjust, barbaric conditions used against Syria’s detainees put them at increased risk of illness and heighten their need for help.

Since the outbreak of the pandemic, trials of two Syrian officers suspected of torture and war crimes started in Koblenz, Germany. One of them was sentenced to four and a half years in prison for his role in crimes against humanity. Several online petitions have been launched, calling for the release of the detainees. Flash mobs of the style I propose will have to be transformed into an online format that, like physical action, maintains the element of surprise and activates social solidarity. A small act of intervention online could be submitting a one-minute note about Syria’s detainees to academic and human rights organizations, perhaps to read aloud at the beginning of their conferences and meetings.

I was 10 years old in 1996, when I moved with my family from al-Hamdaniyyeh district in western Aleppo to historic Qadi Askar in Old Aleppo, where I lived until I left Syria in 2012. I did not see untie his knot performed in either part of the city, but our neighbor in Qadi Askar once asked my younger brother to untie the big toes of her child with alalia.

My brother came back home still dumbfounded by the request, and wondering how he had ended up with such a hefty stash of treats. The tradition might have already been dying out by then, but, more than two decades later, I doubt it is truly dead.

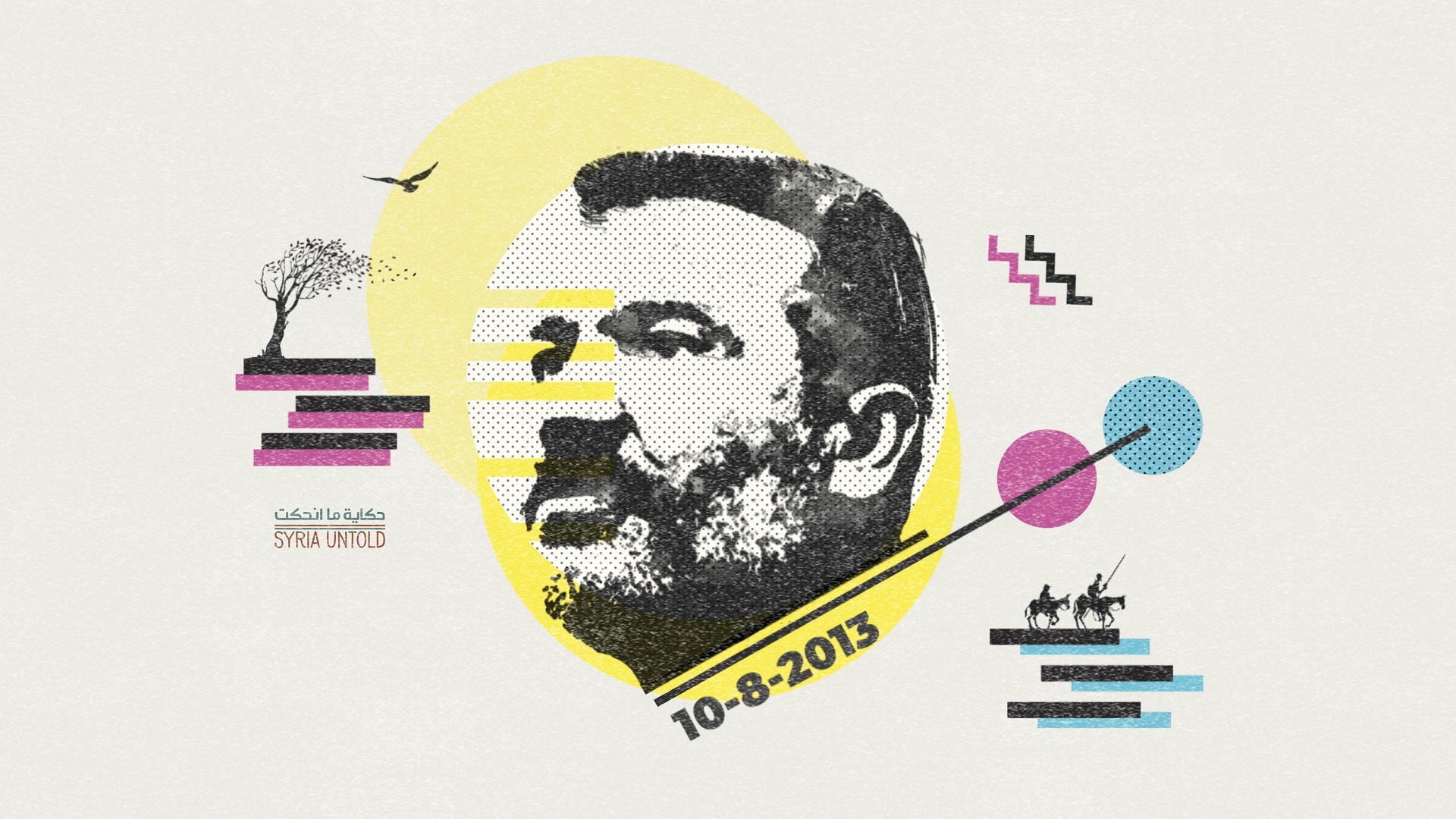

Dedicated to Wafa Mustafa and her family, for their fight for the release of her father, Ali, who has been forcibly disappeared by the Syrian regime since 2013; and to my late father. I am thankful to Karam, Olga and Ben Witorsch for their helpful comments.

My family hopes to publish my father’s book, Features and Portraits from the Heritage of Aleppo, in 2022.