Mapping Lessons (2020) is the most recent film by Philip Rizk, a filmmaker from Cairo. The film is Rizk’s attempt to put different images and political struggles into conversation with each other: from anti-colonialism to the Syrian revolution, from the Paris Commune to the Soviets.

Taking Mapping Lessons as a starting point of discussion, Rizk and writer Leila al-Shami sat down with Enrico De Angelis to explore the relevance of self-organization within the Syrian revolution, and the lessons to be learned from it.

The conversation was edited for flow.

Enrico: Mapping Lessons focuses on the Syrian uprising, among the other recent struggles in the region. How did you decide on this topic?

Philip: November 26, 2013 was the last time I filmed on the streets of Cairo. It was the day the newly legitimized old military regime implemented a new law that banned protests completely. The state could now legally imprison someone just for holding up a sign that read “لا” (“no”) or walking in a group of five people. Not too long after that I moved across the river from Downtown Cairo and, rather than being on the street, I hid in my bed in Doqi reading of elsewhere, pouring my energy into other places and being inspired by other struggles.

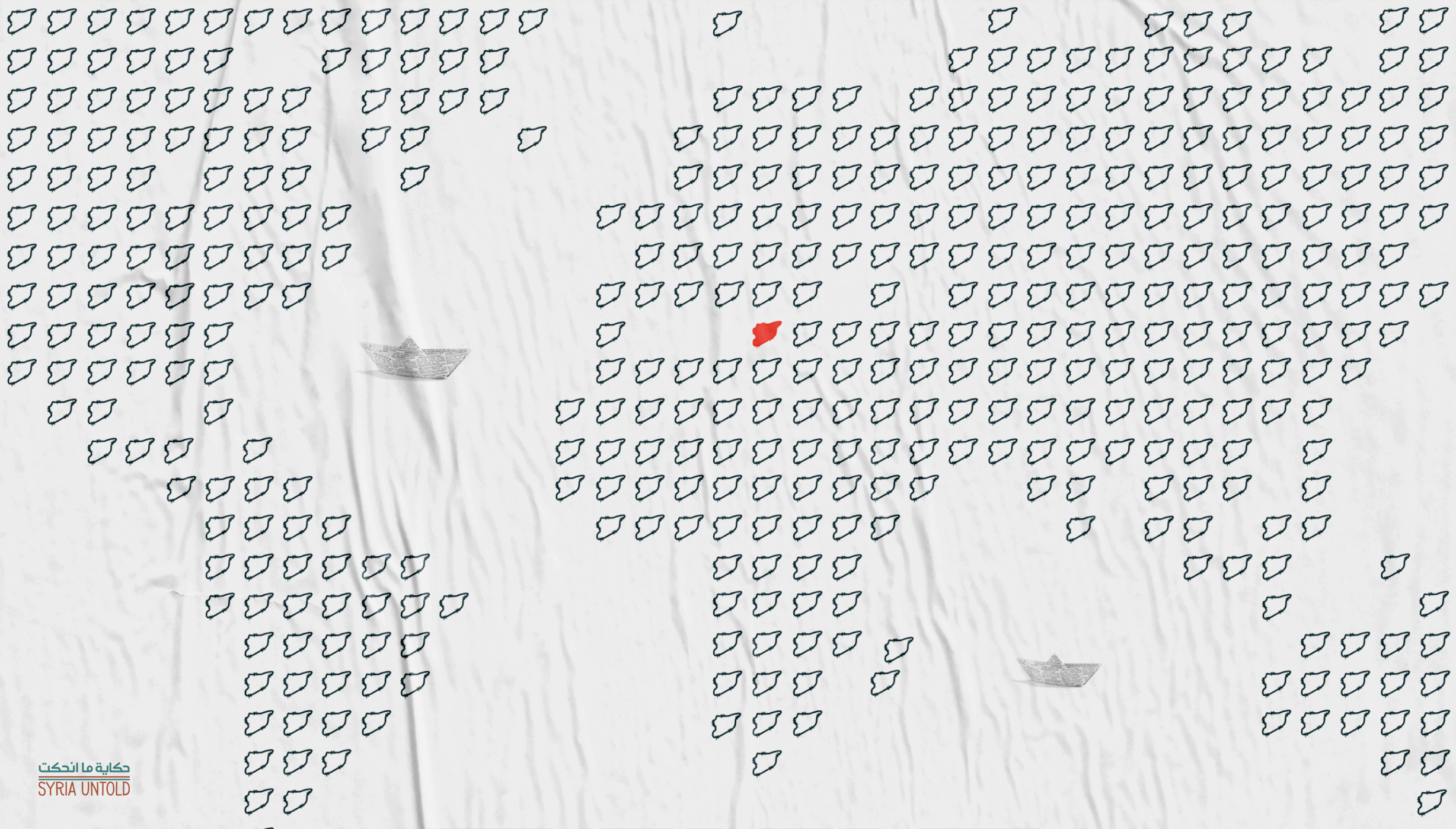

One place I started to look at was Syria, a country that by the middle of 2014 most people associated only with war and a refugee crisis. But it was there that I found the most radical social project the region had witnessed in years, and it wasn’t the Kurdish movement in Rojava as I had first thought. By the end of 2011, as resistance to the Assad dictatorship became armed—with all the power struggles that entails—the regime was forced to withdraw from entire regions of the country. As cities and villages became liberated from authoritarian rule, they set up different versions of local governance, where communities could decide for themselves how to live. The past four years I spent learning more and trying to figure out how to tell that story from my vantage point, not as someone who participated or even witnessed, but someone who fought a similar fight nearby.

In the summer of 2017 a friend asked me why I was working on a film on Syria now, when for most people the height of the political struggle was reaching an end and Syrian activists were flooding into Europe on the refugee trail. The answer only became clear to me later. I didn’t want to inform viewers about what had happened or to advocate for a cause, as is a common use of the documentary mode of filmmaking. We simply don’t have the luxury for that now.

I wanted to imagine what would have been like if these short-lived trials of living in autonomy had succeeded. And since so many of these didn’t last long before being wiped out by various reactionary forces, I wanted to see what we could learn from those radical moments and start a conversation about how to prepare for the next time. Too often we are caught unprepared when opportunity strikes. I also wanted to set the story of Syria in conversation with other places. In the end, Mapping Lessons is not quintessentially a film about the Syrian revolution. It is a film about autonomy, whether in Syria, Palestine, Spain, Soviet Russia, Argentina or anywhere else.

The past four years I spent learning more and trying to figure out how to tell that story from my vantage point, not as someone who participated or even witnessed, but someone who fought a similar fight nearby.

Enrico: We can find different elements in common between a film like Mapping Lessons and many of Leila's writings during the last years, focusing especially on local councils in Syria, and figures such as Omar Aziz, an activist who died in regime prison in 2013.

One is that you both try to connect the Syrian revolution's experience with struggles and histories in other periods and other places.

I think Philip's film in this sense is an effort, through different visual fragments, to suggest new ways to construct a bigger narrative. I say suggest, because it is quite clear that this grand narrative does not exist, and has yet to be found.

Within the margins, and breaking free: Syrian cinema

23 January 2021

A continuity must be explored, also through images. The film is almost a puzzle, offering pieces to the viewer to play with in order to find possible threads and shapes.

Leila, on the other hand, proposes a comparison with the Paris Commune, which in Europe has almost a mythological status. She is one of the very few writers who often mention Omar Aziz, who perhaps embodied more than anyone else ideas that reflect anarchist or communist experiences that took place elsewhere.

So here is my question: is it really possible to dare to suggest these similarities? Syria is associated with war, terrorism and Islamist extremism. Is it possible to find another thread that links it to other diverse radical struggles in other regions and different times? Can Syria become a point of reference or inspiration for class, subaltern, post-colonialist and anti-liberal struggles around the world? For many people this would be almost unimaginable.

Leila: In any culture and historical context, whenever state control breaks down for whatever reason—insurrection, war, economic or natural disaster—communities take power into their own hands and create their own mechanisms for communal problem solving. Examples include the Paris Commune of 1871, revolutionary Spain in the 1930s and Hurricane Katrina, which hit the US in 2005. Syria is the starkest, most recent example of this and so there certainly is a great deal for people elsewhere to learn. There are lessons in creative community self-organization, some of which could be applied in societies where the state has not broken down. Some of the resulting experiments could expand space for autonomous self-organization within state structures and expand people's awareness of the possibilities for self-organization without the state.

It's unfortunate that people in general are unable to learn and study, or even be aware of the lessons from Syria because the presentation of Syria in the West has overwhelmingly been channeled through the discourses that Western culture is already comfortable with. The revolution and counter-revolutionary war is framed in terms of terrorism, the Islamist threat, ancient Sunni-Shia rivalries and the geo-strategic chess games of states. The preponderance of conspiracy theories and propaganda further muddies the waters. All this points to a set of deep cultural problems in the West, which prevents us from listening to the voices of grassroots Syrian revolutionaries and recognizing their accomplishments.

Philip: My sense is that often people believe what they want to believe, or find narratives that work within their worldviews. It is unlikely that such a narrative of continuity of radical community organizing (connecting the communities most affected by Hurricane Katrina, the Paris Commune, 1930s Spain, as well as indigenous community forms of organizing, amongst many others) will ever become a dominant one. But this should not prevent us from making those critical links. It is important for us to also keep seeking out those connections.

Can Syria become a point of reference or inspiration for class, subaltern, post-colonialist and anti-liberal struggles around the world? For many people this would be almost unimaginable.

Maybe it is also important not to think so much about the West and what narratives evolve there, but make available such counter-narratives for communities anywhere to engage with and learn from. After all, day to day life and the dynamics of power relations in Syria are certainly more familiar to someone in South Africa, Indonesia or Algeria than to a majority of people in wealthier countries. But also within that context, the lessons that can be learned from the radical Syrian experience of the revolution are most relevant to communities that are asking these questions, that are concerned with autonomous community life, that are preparing for the next time, wherever that may be.

Leila: I think you are correct in saying that people find narratives that work within their worldviews, and this maybe is the obstacle to being able to really hear counter-narratives from other parts of the world, of being able to truly listen and learn. In some ways it's a problem of cross-cultural communication and the blindness of all of us to our own lack of cultural self-awareness or our own ideological ways of understanding other cultures. It's like the saying: "To step into someone else's shoes, you must first take off your own."

I think many people never question their own ideological assumptions or cultural values. And of course, there's the problem of how to understand Islam and Muslims and the latent Islamophobia, which is a salient issue in the response to events in many parts of the world, from Myanmar to China to Europe and the US.

A decade on, how can we work to free Syria’s detainees?

16 April 2021

Enrico: You both recognize that, though fragile, fragmented, diversified and temporary, the Syrian revolution is one of the most relevant political experiences of the last few years in the region. Omar Aziz said, as Leila mentions in one of her articles: "We are no less than the Paris Commune workers: they resisted for 70 days and we are still going on for a year and a half.”

This echoes the legend of Lenin dancing in the snow, with a champagne bottle, 73 days into the Russian revolution.

Everyone remembers the Paris Commune or the 1917 October Revolution in Russia, and yet only a few seem to consider the Syrian revolution as a significant experience.

Why is it so difficult to acknowledge that relevance? Is it because it is difficult to include it in a grand narrative? What and how should we recover from that experience, and how should we communicate it to the world, so that lessons are learned? I think these questions lie at the center of both your productions.

Leila: We need to be able to listen to voices from the ground and understand them in their own context, and not fall back on preconceived ideological assumptions. It seems in the case of Syria that not only the networks of communication and background knowledge were lacking, but in many cases even the willingness to listen to Syrian voices on the ground was lacking. Many prominent commentators on Syria are neither Syrian nor have relevant expertise or experience of the country. Any progressive politics of engagement with global struggles should therefore take as a first principle that it forms its understanding on the basis of revolutionary voices on the ground. And it certainly shouldn't spend all of its time concerned with the actions and pronouncements of states. This for me was the most important lesson of the past decade; that solidarity must be built from the bottom up.

In terms of the lessons that can be learned from Syria's revolutionary experience, I think Omar Aziz was correct in arguing that protests alone are not sufficient to challenge systems of power. He believed that autonomous community self-organization would allow for resistance over the long term and create viable alternatives to the state's totalitarianism.

This was certainly the case in Syria, where the establishment of local councils and other civil initiatives in the fields of education, health care and media enabled people to take control over their own lives and overcome many challenges, despite the constant onslaught they faced from the state.

I think many people never question their own ideological assumptions or cultural values.

The practical experience of grass-roots democratic organization was a much more powerful teacher for revolutionary Syrians than any amount of theory. For those who experienced it, it seems to have been a powerful, positive and transformative experience. Previously disempowered people in the community became involved in decision-making and community organization; they felt that they had a stake—young people and women in particular. This experience will leave lasting changes on a whole generation of Syrians and the country's future.

Aziz also anticipated that these ways of organizing would increase popular solidarity and social bonds and transform relationships. Certainly, in the early days of the revolution, the movement was defined by its diversity and inclusivity. Men and women from different social backgrounds and religious and ethnic groups managed to overcome previous divisions and work together towards a common goal. This was when the movement was its strongest and had its greatest chance of success, and provides important lessons for those organizing elsewhere.

The other issue which has been at the forefront of the Syrian experience is the debate over militarization. People took up arms to defend themselves and their communities and, given the extraordinary level of state violence Syrians were subjected to, this may well have been inevitable. However, it's certainly the case that the armed struggle was beset by a whole host of problems and challenges, such as the scramble for weapons and funds, a reliance on foreign powers. In many cases, it became a battle for power and territory amongst competing authoritarian (and usually male) groups.

Distorting Syria

23 July 2020

Songs of nostalgia in New York City’s long-lost ‘Little Syria’

05 March 2021

The civil movement, by contrast, remained largely committed to the original goals of the revolution and remained deeply entrenched within local communities. The Syrian experience may then provide lessons for communities elsewhere who find themselves in a similar situation.

Philip: The Syrian revolution has lost the propaganda war. The narrative of that revolutionary spirit competes with so many other narratives, the state-centric ones where the past 10 years in Syria are summarized as a civil war and a refugee crisis due to different forces vying for control, or some leftists as imperial USA’s attempt to overthrow the Assad regime. These meta-narratives are not only selective, but they are also littered with lies because they cover over events to simplify a story their proponents want to sell or, more critically, want to believe in. I am not trying to set up a new meta-narrative, but rather to celebrate one of the most powerful experiments the region has witnessed in its modern history, one that I consider myself lucky to have heard and read about.

I think anyone who is interested in changing the domination of tyranny in the region should take some time to consider and learn. But the film is not an easy one. To watch Mapping Lessons, one needs to open up their senses, to let down one’s guard about what one expects “a film about Syria” to be. To consider the stories of radical social experiments in Syria, we need to likewise let down our fixed collective imaginaries of what happened and allow ourselves to be humbled and learn from powerful communities practicing a radical liberated way of being under very harsh conditions.

Enrico: In this context, why did you choose to use the medium of film?

Philip: To answer this I need to go further into the past. In 1917, when the Russian Revolution succeeded in overthrowing the Tsar, it turned the entire system upside down in Russia. In the world of film, this meant private companies fled to set up their businesses elsewhere and commercial norms of image production were scrapped, while all the makings of state censorship came to an end, at least for a short period of time.

The filmmakers who emerged had not only a clean slate to start imagining filmmaking without the old constraints of commercial gain or state limitations, but they also were deeply shaped by the revolutionary mentality, the completely upside-down way of being of those times. Until that revolutionary moment was quelled by the Bolshevik’s consolidation of power, it meant experimentation was the recipe of the day, the possibility to experiment with how to use images to engage with people within that huge territory to question old habits of being and propose new ones.

Filmmakers also tried out different methods of distribution, setting up traveling cinema boats, cine-trains on which crews could travel, film, process and then screen their work all while on the road. One aspect the most radical early Soviet filmmakers developed was to make images and sound clash, rather than to entertain or comfort viewers by feeding them familiar ideas and images. This form of “Soviet Montage” was developed with the sole aim of allowing the images to create discord with their audience’s expectations. One theorist would later call this process ostranenie, meaning “making the habitual strange.” It takes a lot to get humans to question the way they see things, particularly adults who are set in their ways.

At the revolution's core was the question of self-determination. To what extent can individuals and communities choose how to live on their land, to exercise their power?

While working on Mapping Lessons, I was thinking a lot about this principle of the imaginary, our understanding of the world, how we perceive the world to function, our worldview, or how we imagine the world to be.

In an article you wrote recently, Leila, in which you relate the movement for local governance in Syria to the Paris Commune of 1871, you mention the “collective imaginary,” the shared worldview that people have about political movements. These are the ideas that move us, that shape how we collectively see the world and the events taking place within it. Collective imaginaries help determine, for example, if and how we raise children, or play a critical role in determining what issues we believe in and spend time on, as well as stop us from giving time to others. This takes me back to why I made Mapping Lessons the way I made it.

I don’t use a familiar film language. I didn’t want to tell a story of “important events.” This has been done and it is important that such films exist, even with some issues I personally might have with them. My film is not trying to do what these films are doing, recounting and portraying events of a revolution. Instead, I wanted to allow the images I chose to clash with the imaginary a viewer might have about this time, to allow the images to have an effect rather than support the telling of a story about revolution. In a sense I am demanding more of the images. I am also demanding a lot more from my audience. I believe this form of working with images can allow an audience to question the preconceived notions about what autonomy means, and how local councils can work. The reality is that this form of community governance is an old and tried one, but today in most places it is non-existent because the dominating states of this world haven’t allowed it to flourish.

What I discovered in the case of Syria is that after the fall of the Ottoman Empire, some people started to experiment with local forms of governance, where communities would decide for themselves how to live their lives, rather than follow the laws and regulations set by a centralized power. In less than a year the French colonizers invaded those areas and put an end to these trials, and exiled their leaders. The French then set up the foundation for the oppressive dictatorial state still in power in Syria today, down to the smallest practices of state surveillance and prison systems and torture, a continuity from colonialism to neo-colonialism. With my film I am trying to allow images and sounds to clash with the expectations we have of what is “normal,” how the world is supposed to work, how we are meant to be governed, how we are supposed to grow our food, how we think about education. All these are critical aspects of autonomy we need to think about for the world in which we could be liberated from the powers that oppress us.

‘Palmyra syndrome’: What are Syrians allowed to speak about amid war and revolution?

02 April 2021

The body, between event and memory

25 January 2021

Enrico: Another element on which we can focus is the role of the land. In Mapping Lessons this appears to work as a common thread, a glue holding everything together, even struggles and contexts that appear to be very distant culturally and geographically.

In Leila's writings, the focus on the hyper-local dimension of the revolution brings us also to this element, to the "revolutionary time," as Aziz calls it. The struggle for the land (which involves farming, demographic engineering, urbanism, class and borders) enables us to put together post-colonialist struggles, anti-authoritarian struggles, subaltern struggles.

I think this is also a crucial point, since often even anti-authoritarian movements tend to focus more on the changes at the top of the political systems, or human rights of course. Your work tends to bring back the attention on something more concrete, on the ground level.

Leila: As you rightly point out, one of the defining features of the Syrian revolution was that it claimed territory from the state. After the regime's stifling totalitarianism and control, not only of land, but also the public space, people took immense pride in their autonomy. A video from Yabroud, in the early days of the revolution, showed youth decorating roundabouts and public squares with flowers, and painting them in the colors of the revolutionary flag. Graffiti artists decorated spaces which once only showed images of the president. The revolution sparked such a diverse array of community initiatives. At the revolution's core was the question of self-determination. To what extent can individuals and communities choose how to live on their land, to exercise their power?

Omar Aziz saw the importance of land to the Syrian struggle. He said in one of his papers that one role of the local councils should be to "defend the land in the region from being expropriated by the state, because such expropriations of land in Syria's cities and countryside and the consequent displacement of their inhabitants are one of the core pillars of the politic of domination and social exclusion on which the regime relies." This was written in the early days of the revolution and Aziz was referring to policies of state expropriation of land which preceded the revolution and which he believed was a key impetus for it to happen. He said that the revolutionary movement in rural and suburban areas arose partly due to people's rejection of being severed from their subsistence base.

This policy has only intensified as a counter-revolutionary strategy. When the regime reclaimed territory, which it fought hard to do with heavy bombardment and the implementation of starvation sieges, a key policy was to displace the original inhabitants; the population that had resisted the regime and that it could not control. We've seen massive waves of forced displacement. The land which the regime has regained has been given over to loyalists—whether regime cronies who will develop the land by building housing and shopping malls which are unaffordable to the original inhabitants, or by handing over land and property to families of regime-affiliated militia or even foreign powers. Iran is buying up real-estate in strategically important cities and border areas. This way the regime ensures a loyal constituency and its continued domination of territory. And now that so many Syrians are exiled from their land or even the country, we are faced with questions of how to continue (or rebuild) a movement given this geographic dislocation.

Philip: Leila your words cut to the bone and get to the heart of the matter. The struggle in Syria has been one for life, choosing to live it, to live it freely, communities in the form of networks or geographical communities banding together to throw off their oppressors. The price has been unfathomable, because the struggle is for the most basic and most critical thing: land.

The Zapatistas say that every struggle must be connected to land, that without land there can be no autonomy. In the city we often forget the importance of land. We live on land, but also we eat from the land. To me a clear distinction between the revolution in Egypt and in Syria is that the latter took land from the state. The equation of these two struggles is a completely different one. I think it is also why it was so easy for a majority of the world to support the Egyptian revolution, because it didn’t shake the system of power at its core, and thus allowed space for the regime to reemerge. In Syria, the regime reacted like a rabid animal when revolutionaries took territory away from it. At all cost it has fought to get it back.

Besides countless forms of the most brutal violence, the regime used sieges on these autonomous areas, bombing bakeries and wells, using the tactics of bare life in the struggle for control over that bare life. The regime would starve the population before ceding any bit of power. Land is at the crux of the matter because without it we wouldn’t exist. So if we think about the next time we absolutely need to take land into consideration. How do we feed ourselves from it, how do we share it amongst each other, how do we live on it, how do we defend it, but also how do we respect it? While working on my film Mapping Lessons I found that struggles around the world across time and place have these questions in common, which can be critical to create solidarity amongst us but also to teach us to look elsewhere for lessons to be learned, for inspiration and hope.