This essay is part of SyriaUntold's series on Syrian theater. Read this piece in its original Arabic here.

The Syrian theatrical movement in Lebanon witnessed significant activity with the influx of Syrian refugees, peaking between 2012 and 2015. There were multiple theater festivals, including “Miniatures: A Month for Syria” in 2013 and “Arab Theatrical Platform Agora” in 2014. In 2016 was the “Create Syria” forum, and 2019 brought the “On the Brink of Change” forum. The year 2018 alone saw five Syrian plays staged.

2020 and 2021 are difficult to evaluate because of COVID-19 restrictions that impacted the theater scene. The flow of Syrian artists to Lebanon has also dwindled since 2015 as many of them have relocated to other countries.

Following Syrian theatrical production or the Syrian theatrical movement in Lebanon over the past decade requires an elaborate, specialized study in search of statistics and prevalent theatrical forms, or those that stood out in Lebanon particularly. It requires that we address questions about the artistic and creative aspects of such work, and the dominant theatrical trends. During this period, theatrical activities varied: from festivals and forums to workshops in writing, acting and directing, theatrical readings and interactive and professional plays. The scope of this article only allows us to tackle the basic theatrical forms and trends.

Syrian productions in Lebanon took on different theatrical forms: storytelling, shadow plays, puppetry, multimedia theater and physical theater. There were also diverse schools and trends to which the theatrical shows belonged: interactive theater, realistic theater, existential theater, absurdism and fantasy theater. Theatrical themes incorporated all topics that emerged with the social and political experience that Syria has been living since 2011.

The romantic liaison becomes a motor element pushing the characters towards engagement with political and social issues.

Plays tackled the key topics of that period, such as political revolt, protests, oppression, arrests, proliferation of arms, destruction, forced displacement and migration. The theme of women’s emancipation and social justice were particularly highlighted.

Theatrical inspiration from stories of the marginalized

Perhaps the projects that drew their themes directly from social groups, or those that engaged with them in writing and acting the scripts were among the most popular forms of Syrian theater in Lebanon. They varied from theater of the marginalized or the oppressed, interactive theater and asylum theater, because they often worked with Syrian refugees in Lebanon and tackled related themes.

Syrian theater through a decade of war

01 June 2021

Current conditions of Syrian theater

28 May 2021

Some of them resulted in plays like Our Tent (Khaymatna, 2014) as part of an interactive writing workshop with amateurs from the al-Marj camp in Lebanon’s Bekaa Valley. Omar al-Jabaei wrote about this play: “They are the ones who chose the themes of the play, and paradoxically, they did not talk directly about asylum, violence, racism or aid, although they are all affected by these issues. Instead, they chose two topics from daily life, reflecting all the above without addressing it directly. They just talked about love and boredom.”

In the play entitled A Thousand and One Tents (Alf Khayma wa Khayma, 2014), the participants performed stories related to the decision of the Lebanese authorities to shut down al-Marj camp. The inhabitants of 42 tents had to move in record time to an unknown fate.

The scripts of this workshop focused on stories about place, memory and being driven to the unknown. Ammar Abou Hamed wrote: “The narratives focus on the intimacy among the camp residents, their daily relationships, and the camp’s prominent figures. The underlying sadness in the readings of A Thousand and One Tents stems from having to leave the camp and being driven away from their memories. The show presented, on stage, the human narratives related by the people who experienced them in reality.”

Plays based on human rights reports

The Scenario Workshop stood out in this theatrical style, staging a play called Transformations (Tahawoulat, 2018) with a group of young Syrian, Lebanese and Palestinians aged 15-20 years old. The play combined Franz Kafka’s novel Metamorphosis and scripts written by participants tackling themes like discrimination, refugee identity, camp culture and the power of customs and traditions in a patriarchal society. In 2020, the Scenario Workshop completed a play entitled In the Middle: Writings of 17 Syrian and Lebanese Women. The story is about women who decide to travel to the moon to break free from the conditions of life on Earth. While we follow their impossible journey, the stories of Syrian women who sought asylum in Lebanon are revealed. The play highlights the difficulty of living in uncertainty, torn between an impossible return to the past amid the existing obstacles and the unknown looming over the future.

Silk (Harir, 2020) is a play presented by a group of displaced Syrian women in Lebanon, who received training in story-building and the fictional world, leading them to stand on the stage and perform. Director Sarah Zein writes in the play’s brochure: “Just as women weave silk patiently, they wove their world and told their stories in this play.” The performance reflects stories of women in asylum experiencing the absence of their husbands as well as censorship on love and feelings and nostalgia for memory and old places.

In this context, Shadows (Khayalat, 2018) was an innovative initiative that aimed to create a theatrical performance based on the reports of human rights organizations. The starting point of director Sari Mustafa for this play were documented testimonies of female relatives of Syrians disappeared since 2011, whether they were detained by the regime, kidnapped or went missing with their fates still unknown. The play is based on a report released by the Dawlaty and Women Now organizations, entitled Shadows of the Syrian Disappeared: Testimonies of Female Relatives Left with Loss and Ambiguity.

Theater as a narration tool

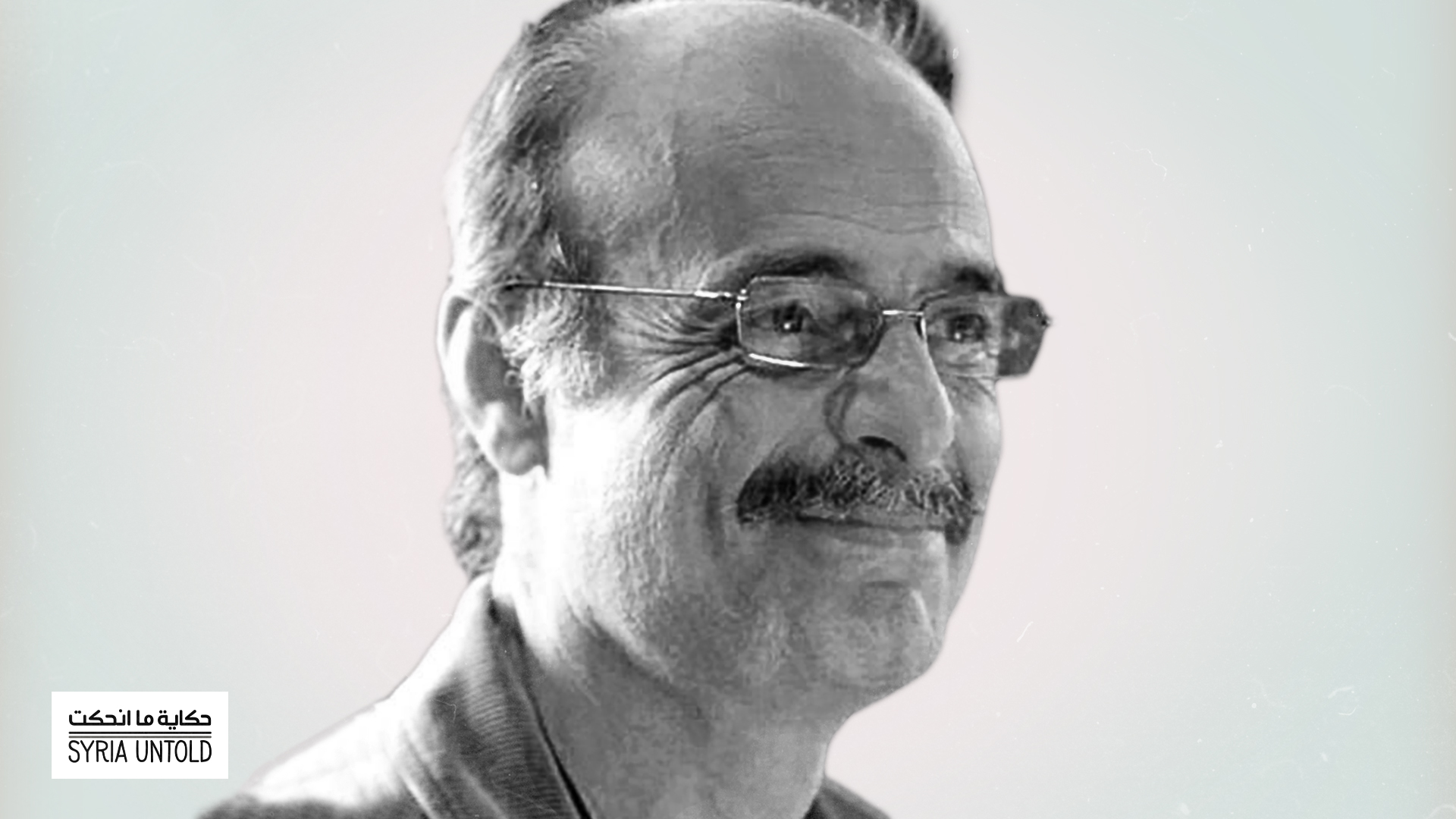

The question of how to tell the Syrian narrative has been one of the main themes in Syrian theatrical productions since 2011, and not just those produced in Lebanon. Wael Ali tackled this question early on in his play I Don’t Remember (Ma Aam Etzakar, 2014) by delving into the memory of a Syrian political prisoner who was released in the 1990s, and interviewing him directly on stage to highlight the selective aspect of memory and the uselessness of relying on it to document narratives.

In the The Wedding (al-Ourss, 2014) Rafat al-Zakout tries to use the techniques of storytelling and puppetry to tell the story. The play opens with the storyteller saying: “Our story is one of a kind. It is pieced of lumps in people’s throats. It is a tale of highs and lows, and of a country and its people. It is a story marked on the calendar and scribbled in a notebook. Remember, remember O Syrians!”

Songs of nostalgia in New York City’s long-lost ‘Little Syria’

05 March 2021

As for connecting narratives to memory, Wael Kadour’s play Touta, Touta, and the Story Begins (Touta Touta, Ballashet El-Hattatouta, 2015) tells the story of Syrian man, Hadi, who wakes up one day in Lebanon with amnesia. He tries to gather his stories through a theatrical script he finds among his papers. Eventually, his search within his own memory leads to a search for the Syrian socio political event. In another experience, Kadour relies on global theatrical scripts in his play The Confession (al-Itiraf, 2018), directed by Abdullah al-Kafri. In the play, Kadour tackles the theme of the victim and the executioner, based on the script Death and the Maiden (1990) by Chilean playwright Ariel Dorfman.

The experience of the playwright-director duo Mohammed al-Attar and Omar Abusaada resulted in three plays within this framework. Could You Please Look into the Camera? (Fik Tettala’ Aal Camera?, 2011-2012) tells the stories of prisoners and describes torture practices through the account of the main character, Noura, who tries to produce her first film by collecting prisoners’ testimonies. Throughout her journey, we read in the script and see on the subtitle screen the prisoners’ testimonies, which the writer gathered from different prison experiences during the first months of the Syrian revolution.

In al-Attar and Abusaada’s plays The Trojan Women (2013) and Antigone of Shatila (2014), they mixed personal testimonies of female refugees and Sophocles’ scripts to blend the stories of Greek tragic characters and those of Syrian women in Lebanon.

However, we notice the absence of documentary theater, which German writer Heinar Kipphardt established in his play The Case of Robert Oppenheimer (1964). Kipphardt defines this genre as theater that uses reports, investigation records, administrative files, letters and statistics, not just to write a play, but also to reveal them to the audience during theatrical narration. This theatrical genre is rare in Arab theater. The only Arab play that can be strictly classified as such was not Syrian, even though it tackled a case related to exploitation of Syrians in Lebanon. Lebanese theater director Sahar Assaf presented the play No Supply, No Demand (La Aard, La Talab, 2019), in cooperation with the American University of Beirut (AUB) Theatre Initiative. The play talked about a prostitution and human trafficking network, which exploited 75 Syrian women in Lebanon, and used the techniques of documentary theater.

Realistic theater: An expression of the here and now

Many Syrian theater directors and playwrights in Lebanon resorted to realism to make their ideas heard or to create characters capable of acting out themes they wanted to express. The three scripts arising from the Writing for the Stage workshop in 2018 tended to realism. Writer Wassim al-Sharqi presented his script entitled Short Romantic Film as an “attempt to search for that narrow space associated with the changing dynamics between a group of friends who met during the university days, but whose fates were affected by the political and social events that have occurred in Syria.” The script Your Love is Fire (Houbak Nar, 2017) by Mudar Alhaggi focuses on love in times of war. One character, Rand, tries to convince Khaldoun to defect and escape mandatory military conscription. Consequently, the continuity of the feeling of love becomes tied to the answer to a current social dilemma in Syrian society—whether to leave or stay.

Realistic plays tackling the theme of women’s emancipation notably attract a wide audience. In the realistic narratives, that link between the revolution and women’s emancipation is underscored. Such plays include Kadour’s Chronicles of a City We Never Knew (Waqa’eh Madina La Naarifouha, 2019). In the play, Kadour attempts to paint the features of a lesbian relationship through the story of Nour and Roula, linking this relationship to the social and political events in the country. While Nour is committed to the opposition movement that kicked off with protests, Roula is influenced by her and follows suit. Eventually, they are both arrested. In such plays, the romantic liaison becomes a motor element pushing the characters towards engagement with political and social issues.

Within the margins, and breaking free: Syrian cinema

23 January 2021

Land, revolutions and lessons from Syria

04 May 2021

Kadour’s Touta Touta play links women’s emancipation to the Syrian revolutionary movement through the desire of one character, Najla, to become an actress. Najla only manages to confront everyone with her desire to study acting at the moment she begins participating in the protests. In al-Attar’s Could You Please Look into the Camera? the character Noura’s desire to produce her film goes hand in hand with her rebellion against the constraints imposed by her older brother Ghassan, who forbids her from participating in the protests.

Existentialism and theater of the absurd

The questions raised by existential theater are also present in Syrian theatrical productions in Lebanon. Sari Mustafa’s Awakened Monologue (Estafaqt Monologue, 2013) focuses on questions about the self, freedom, existence, nihilism and death. In this play, awakening signifies freedom, but it also signifies death. The director writes about the main character in the presentation of his play: “Between reality, imagination, life and death, he experiences it all—from his thoughts to his experiences—to become himself and to draw a line to man’s continuity. His dreams and hopes remain an obsession for him, and death remains the reality of life.” Many traces of the style and elements of theater of the absurd can be found in Mustafa’s second play, The Center (al-Markaz, 2014).

Fantasy theater

In Awakened Monologue, the deceased speaks to us after his death. It is a surreal fantasy seeking to make a philosophical statement. The play The Other Side of the Garden (Al-Janeb al-Akhar Min al-Hadika, 2018) by Koon Theater Group, is based on the fairytale The Story of a Mother (1847) by Hans Christian Andersen. In the tale, the angel of death abducts a child. the child’s mother embarks on the journey of death—purgatory—in search of the angel of death, to reclaim her child. The surreal constitutes the key narrative threshold of the story. The play excels in employing its projections on the presence of death in the Syrian experience and the experience of loss for families. The director, Ossama Halal, chose to use a puppet to represent the angel of death on stage, and several performers took turns to build a relationship with it. A fictional setting prevails, represented by the road to death or the afterlife on stage, making it a fantastical imaginary place.

Puppetry, shadow plays and multimedia theater

In the puppetry field, the One Hand Puppet Theatre Company emerged in 2017, composed of Syrian refugees from Beirut’s Shatila camp. They presented several plays, including More Than an Artist and Puppet Autoportrait (2018), in which puppets rebel against their puppeteers and demand their rights. Planets’ Street (2019) uses a science fiction plot about children’s isolation on digital planets to express how digital media have stolen childhood and to depict estrangement from the actual, tangible experience. However, the play does not criticize digital media and the use of technology per se.

In Cordello’s Imagination (Khayal Cordello 2019), director Omar Baqbouq blends shadow theater with the selfie video that went viral in Syria with the onset of the revolution. This multimedia theater falls under what Patrice Pavis describes in his Dictionary of Theatre as “intermediality,” as the performers are connected through the internet and communication apps. The director explained his technical choice, saying: “The play is about isolation and fear. It attempts to unite the Syrian audience on one platform, especially after the war dispersed people, forcibly displaced them and besieged them. The play taps into the technique of livestreaming on social media.”

Conclusions:

- Tracing the Syrian theatrical movement in Lebanon during the last decade requires more research and study, especially in light of the lack of statistics and documentation projects in this regard.

- Syrian theatrical activities in Lebanon included various forms of events, including festivals, forums, workshops, readings and plays.

- The genres of Syrian plays in Lebanon varied and included artistic and intellectual theater currents. Interactive theater was particularly prominent.

- Theater has been used widely in cultural development projects for marginalized groups in various forms, most notably workshops in writing and performance. Interactive theater dominated the use of arts in the field of societal change and cultural development.

- The support programs offered by cultural and development institutions played a fundamental role in maintaining the continuity of Syrian theater productions, and the artist’s ability to continue to produce theater in host communities.

- Syrian theatrical productions in Lebanon tackled themes expressing the experience of Syrian society since 2011.

- The themes of women’s emancipation, equality and social justice have also notably emerged.