By Abir Kopty and Enrico De Angelis

We cannot underestimate the battle of narratives around current events in Palestine. The outcomes of this battle, including on social media, will likely have deep repercussions on how Palestinian issues will be framed in the future. Sure, certain politics always have the upper hand vis-à-vis mass media. Still, how the media frame an event can open new ways of thinking about an issue, and thus can pave the way to different political approaches.

In this article, we offer a broader perspective on how the events in Palestine were narrated in recent weeks, between old challenges and, perhaps, new trends.

Indeed, if we look at the current situation from a media perspective, the picture appears mixed, combining the old and the new.

‘Palmyra syndrome’: What are Syrians allowed to speak about amid war and revolution?

02 April 2021

Land, revolutions and lessons from Syria

04 May 2021

Old strategies at work

As soon as Hamas launched rockets against Israel last May, a series of traditional media and PR strategies immediately activated. Navigating through much of the coverage and statements by Israeli and Western officials was like experiencing déjà vu.

The issue was overwhelmingly framed as a two-sided "conflict" between Hamas and Israel. Palestinians were frequently blamed for Israel’s aggressions, while a lack of accountability for Israel’s actions loomed heavy and silent. Sometimes even factual terms such as "occupation" or "occupied territories" seemed to be, once again, journalistic taboos.

These media strategies have a long history. As Palestinian-American historian Rashid Khalidi points out, the definition of the Palestinian identity was always at the core of the conflict of narratives. After the creation of Israel in 1948, the Palestinian people as a distinct nation was completely erased, in accordance with the Zionist myth of "a land without a people for a people without a land.” In the media, Palestinian people became invisible.

Over the course of the Arab-Israeli wars, Palestinians were barely mentioned in the media and in political discourses. It took years of struggle to gradually push mass media and the international community to stop denying the existence of a "Palestinian people.” During the phase of PLO’s lead armed struggle against Israel, Palestinians were framed as “terrorists.”

The 1987 Intifada was a turning point—almost a unique event from a media point of view—as Palestinians imposed themselves as protagonists in the news coverage. After 20 years of being framed simply as “terrorists,” their struggle was increasingly recognized as a legitimate one.

In the two decades following the Oslo Accords, however, coverage shifted yet again against the Palestinians. The events of September 11th of course played a crucial role, creating a cultural environment that made it very easy for Israel to present itself as an outpost against “Islamic terrorism.”

In many ways, the coverage of the latest round of dispossession and deadly bombing in May 2021 tends to adhere to the same logic and trends.

The denial of Palestinians as a unitary people emanates from Israel’s separation of them along manufactured geographic divisions. Palestinians in Jerusalem, in Gaza, in the West Bank and those inside Israel were treated as different entities.

For Palestinians in Jerusalem the narration was about “evictions” rather than forced displacement and dispossession of family homes—a matter of “real estate disputes” to be discussed in courts. In Al-Aqsa it was a matter of “clashes.” In Gaza, it was about the “conflict” between Israel and Hamas. And, for Palestinians in Israel, mass protests were reduced to a matter of “riots,” of "law and order" and a “challenge to coexistence.”

Palestinians with Israeli citizenship were often labelled as “Arabs,” in opposition to "Jews," suggesting a cultural or ethnic problem rather than a political one.

In the case of Gaza, framing the issue as a two-sided conflict exempted the media from addressing the daily living conditions of Palestinians under the 15 years of blockade imposed by Israel. Ordinary people are reduced, at best, to "human shields." Within this narrative often there was the tendency to stress that Israel was targeting only Hamas, and not Palestinians, as if Hamas was not a component of Palestinian society.

In the end, the issue was reduced to a matter of Israel’s security, in line with the leitmotif of "Israel has the right to defend itself," which was soon repeated as a mantra by official spokespeople and analysts, especially in Europe and the US.

For Palestinians in Jerusalem the narration was about “evictions” rather than forced displacement and dispossession of family homes—a matter of “real estate disputes” to be discussed in courts.

Old accusations and bad coverage

These old strategies seemed to be, at least in the first phase, quite effective. This success depended not only on well oiled PR mechanisms or pre-determined cultural backgrounds, but also on more structural flaws inherent to the mechanisms of news production.

Mass media tend to cover the surface of the latest events, without offering the broader context. When weapons fire, outside journalists parachute in and cover the fighting. Their narration of events often remains superficial and anchored to the present.

But this lack of context is particularly problematic when it comes to Palestine. The daily realities under occupation, living conditions in Gaza, processes of colonization across historic Palestine are left outside of the picture. The historical context is conveniently ignored—it is “too complex.”

And yet, providing context is not so very difficult. An Egyptian-American content creator, for example, was able to explain this “complex” issue and provide historical background through a 1.5-minute sea shanty, which she published on her TikTok and Instagram accounts. The video went viral.

A decade on, how can we work to free Syria’s detainees?

16 April 2021

Hala Abdullah: 'I believe in cinema as a means of resistance’

11 June 2021

Edward Said defined the Israeli-Palestinian issue as the "most geographical of conflicts." And yet, maps are almost always (and conveniently) missing in coverage of Palestine. Without a geographic visualization, it is impossible to fully grasp the extent to which Palestinian land has been fragmented, its territories stolen and its people weighed down by Israeli colonization policies on the ground.

Such absence also contributes to presenting the roots of the story as prohibitively "complex," an argument that translates into a shield that prevents any questioning of power structures.

Without context, the audience is left with merely a “conflict,” which suggests there are two sides with a symmetrical power.

In many cases, the symmetry was even flipped, and Palestinians were framed as the aggressors. Outlets like AP and BBC described Palestinians as "dying" while Israelis were "being killed." The AP headline was replicated unchecked by many news outlets.

Are the times changing?

It is in this context that a massive, perhaps unprecedented, grassroots campaign on social media and other platforms took place. Palestinian activists and journalists, but also an array of actors at the international level, began this past May to challenge pro-Israeli narratives as never before.

At first the task appeared overwhelming. The social media space appeared quite hostile, while Facebook, Instagram and Twitter were accused of obscuring or even silencing critical voices.

When it comes to the media field Palestinians are at a disadvantage. They suffer from a digital gap because of the lack of infrastructure and because of the capillary forms of control and censorship exerted by Israeli authorities, often with the complicity of US tech giants such as Google and social media censorship platforms.

Palestinian media activists and others applied different strategies in order to fight this hostile virtual environment. They attacked social media giants directly in different ways: downrating campaigns, media coverage critical of their policies and exposure of episodes of censorship. Facebook and Google employees spoke up demanding transparency and change of policies of the platforms. Users changed words and terms in Arabic to disrupt and confuse the algorithms. The “Dotless Arabic'' initiative provided another solution: to write in Arabic without dots. Activists also posted personal photos in the middle of political posts to throw off certain platforms’ algotherims.

More importantly, when the media campaign grew bigger, it became more difficult for the platforms to censor and silence all the content. There are limits to the extent of content a monitoring team, however big it may be, can handle.

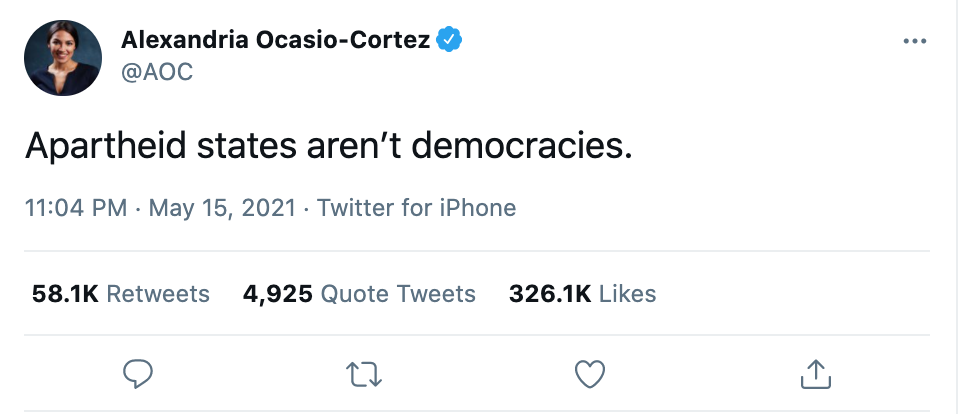

The tweets and posts began to accumulate into a media avalanche, and it appeared the tide was perhaps, for the first time, turning. A number of TV celebrities became more outspoken. John Oliver, a British-American comedian, accused Israel of "war crimes" in a section of his talk show. MSNBC host Ali Velshi explicitly called out Israeli apartheid. Even within the American Congress, the approach to the issue appeared to be shifting. Bernie Sanders and Ilhan Omar were very vocal about the situation as were Rashida Tlaib, Cori Bush, and Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, who tweeted: “Apartheid states aren’t democracies.”

The fact that US politicians and so many celebrities began to talk about the issue and challenged pro-Israeli narratives had a direct impact on US media. As communications scholar Daniel Hallin describes in the context of the Vietnam War, the “objective” model of US journalism means that when elites are divided, that division is reflected in the media.

So it is not particularly stunning that today, political views that before were absent from outlets such as The Washington Post or Newsweek suddenly began to find space.

Still, even the fact that The New York Times for the first time decided to dedicate its front page to name the children victims of the bombings should not give the illusion of a substantial change in the editorial line. First, presenting the victims without contextualizing them is still problematic for the reasons we explained above. Second, as Belen Fernandez and Fady Joudah rightly point out, The New York Times, as most US media outlets, continue devoting much of their space to pro-Israeli narratives and their advocates.

At the same time, also within media organizations some new developments are emerging. In an open letter, hundreds of journalists, including reporters from The Washington Post, The Wall Street Journal and The Los Angeles Times, called for an end to obscuring the oppression of Palestinians in the press.

We also cannot ignore the impact of two important reports, published by the Israeli NGO B’Tselem and Human Rights Watch, recently labelling Israeli domination in Palestine as “apartheid,” a word that before was used only among specific circles of activists and academics involved in Palestine.

Palestinians’ new communication approach

However, none of these shifts would have been possible without the emergence of new Palestinian voices challenging incessantly the traditional narratives. It is here that the major changes took place.

We are witnessing the rise of a younger generation of Palestinians appearing on screens and claiming public space to explain context, history and perspective with an unprecedented clarity and directness.

El-Kurd simply asked in response: “Do you support the dispossession of me and my family?”

We are seeing more and more voices refusing to be relegated to a defensive position and be polite to please Western audiences. Palestinian speakers are more ready to speak unapologetically and to challenge questions rather than just answering them, and because of this they have received growing online support.

A distinct moment representing that shift was Palestinian writer Muhammad El-Kurd’s interview last month on CNN. A reporter asks him: “Do you support the protests? The violent protests that have erupted in solidarity with you and your family?” Instead of answering, El-Kurd simply asked in response: “Do you support the dispossession of me and my family?”

This interview set the tone for many other Palestinians appearing in the media. We are seeing younger voices, among them many women, who are able to communicate in the media as their predecessors were never able to do.

Moreover, these new voices are very careful to present their struggle as a unitary one and challenge the idea that we should consider the Palestinian issues separately. People from Gaza, Jerusalem, the West Bank or inside Israel tend to stress in the media that the roots of the problem are shared, even if they live under disjointed and different conditions. The results of these efforts is that today, for the first time, words such as "apartheid," "ethnic cleansing," "persecution" and "settler colonialism" can circulate more and more, even reaching mainstream media.

A ‘war of position’

Outside media attention on Palestine has already faded since last month. This was predictable and inevitable. When heavy weapons stop firing, the media tend to turn to somewhere else.

The daily life under the occupation, the blockade on Gaza, the plight of Sheikh Jarrah or Silwan and the mass arrests of Palestinians are not as newsworthy as missiles and rockets crisscrossing the skies.

Still, we cannot erase what was achieved in recent weeks: a notable shift in the narratives and the language used to narrate Palestine. New conceptual tools to approach the issue are now more available on a much larger scale.

A new generation of voices, young and female, gained access to mainstream media spaces, spaces we can hope they will no longer be excluded from. They know how to communicate with a younger public, and with international media. It would be difficult, albeit not impossible, to push them back again.

Particularly relevant is the change happening in the US, the main diplomatic and material supporter of the Israeli occupation. Here, years of work and organization by Palestinian movements are finally giving fruits. Groups like IMEU and the US Campaign for Palestinian Rights are leading an approach of intersectionality with other oppressed communities in the US. Edward Said always lamented that Palestinians in the US could not organize themselves to communicate more effectively and be more vocal, the way pro-Israeli groups had long done. Now this is changing.

Black Lives Matter also played a crucial role. The movement promoted political discourses and vocabularies that handed the US public new tools to grasp and relate to the Palestinian reality. This development contributes to offer another dimension, more inclusive than the more traditional anti-imperialist, leftist identities that characterized it in the past. That is a dimension of intersectionality that connects today Palestine with anti-colonialist, anti-racist struggles all over the world.

Much remains to be done. We are witnessing, to paraphrase Gramsci, a “war of position.” It is a long way before certain narratives can become more hegemonic, and thus leverage more accountability and a material change on the ground.