Sultana was the eldest daughter of Nuri, who herself died in 2009 after living almost 100 years, the eldest among three brothers and a little sister. They married off Sultana at age 14 to Al-Mullah Muhammad Neyo, my grandfather.

She had been playing with mud behind her house made of mud when she married her cousin, who was 13 years her senior. She left to go live in another village, in the home of her brother-in-law who owned farmland there. After that, she moved to another village in the same area, where her husband found work as a sheikh in the mosque. They stayed there only two years, as my grandfather didn’t like working as a sheikh and living off the donations of the poor. He decided to move to Qamishli. Sultana returned, without her husband, to her brother-in-law’s village to wait until Al-Mullah found work in the city. It was in that village that she gave birth to her first son, my father.

Over the course of my father’s first year, Sultana’s husband joined the first Kurdish party and was one of the first Kurdish political figures in Syria. The little family soon joined him in Qamishli, settling in a neighborhood on the outskirts of the city. My grandfather worked as a clerk for one of the sheikhs there. Their first daughter, my great aunt, was born. Ten days later, my grandfather was arrested in Aleppo during one of his party missions. They transferred him to Mezzeh Prison in Damascus. This was during the period of unification between Syria and Egypt. Gamal Abdel Nasser, who founded the ruin we now live in, was in charge of Syria.

Al-Mullah’s detention lasted six months, though he remained on trial for a year and a half, which forced him to stay in Damascus to appear in court each week. He didn’t have the money to go visit Qamishli and return regularly. So he found work in a clothing factory in Damascus’ Sheikh Khaled Rukn al-Din neighborhood. At the same time, Sultana could no longer pay rent for the house in Qamishli, so she returned to her father’s house in their remote village outside the city. Her father died after her return.

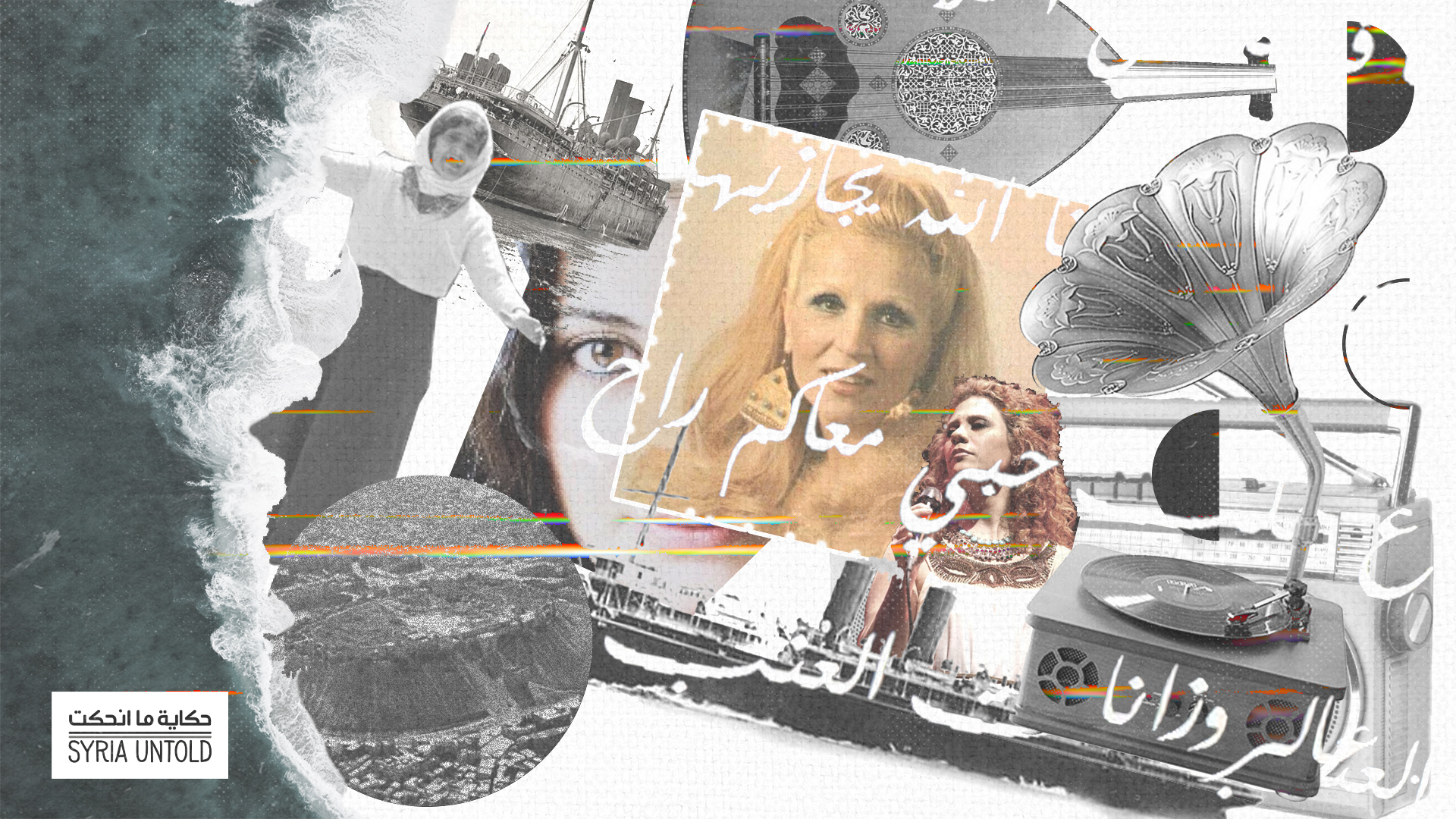

Songs of nostalgia in New York City’s long-lost ‘Little Syria’

05 March 2021

When Syria split from Egypt and the union dissolved, the new Syrian government issued a general amnesty for convicts. And so my grandfather came home to their new house. The family went back to Qamishli and rented a new house in the Qodorbak neighborhood, where my grandfather made shoes. But only a short while later, the mukhabarat came back to pursue him, forcing him to leave and hide among the villages.

During those days, when he was visiting the family in secret, the security forces raided the house and arrested him again. They took him to Habsa Rash (“The Black Prison”) in Qamishli. This was in 1962. They released him after 40 days. Afterwards, he joined the Kurdish movement in Iraqi Kurdistan. His duties included transporting journalists to the mountains and delivering medical supplies and sometimes weapons.

Sultana returned to her parent’s house once again, to live with her mother. She had no breadwinner during this time. After a number of months went by, she decided to move to Qamishli again for her husband’s sake. Travelling to Qamishli is easier than to the villages; my grandfather would move between both sides of the border like a wolf.

She borrowed a lot of money to prepare the house in Qamishli, until her third son was born in 1964. When he reached six months old, the security harassment increased, and she left the city with her children. They settled in the village of Shuri, which belongs to the Kikan clan. They thought that the government wouldn’t find them there, amid the security chaos enveloping much of the country at the time.

But a mukhabarat agent saw them and informed on them. They raided the house one day as the family was eating their suhour meal, during Ramadan. They broke down the door of the house and entered. Sultana’s 10-year-old brother was living with them at the time. Picture it: a woman and four children, and security personnel attacking the house. They stayed in the house for hours, hitting and insulting the family. They beat the children, as well as Sultana herself while she was holding her baby.

I’ve heard this story dozens of times, to the point where I almost feel as if I was there, that I can see everything that happened.

The small village was empty. After residents heard that the security forces had raided one of the houses, they fled to the surrounding fields and farmland. The security guards threatened them daily, taking them to Ghweiran Prison in Hasakeh. They made the children walk with machine guns pointed at them, Sultana walking behind them. They told the family they would never return to their home.

They stopped them in front of a military vehicle and turned towards a woman who was passing by the village carrying water. Three soldiers stayed with Sultana and her children while four went towards the strange woman. They asked the woman about Sultana’s husband, if she knew Al-Mullah. The woman responded that the soldiers were a disgrace to harass a mother and her children. This angered the soldiers, who beat the woman, smashing her water jug and bloodying her face.

I’ve heard this story dozens of times, to the point where I almost feel as if I was there, that I can see everything that happened. I see the young boy approach, a relative of the beaten woman, trying to defend her. They caught him and tied him up after beating him too, then told him to beat Sultana and her children if he wanted to survive. The boy refused, so they beat him harder. Sultana tried to protect him despite her weakness, but they only beat him more. They smashed his jaw with their feet, and blood flowed like rivers. The soldiers left the sight of the blood, saying nothing but insults, which Sultana was ashamed to mention when retelling this story.

She tried to help the boy to the extent that she could, but she couldn’t stop his bleeding. Residents of the village came to help after they saw the security personnel leaving. They pulled the boy in a cart to a doctor in the town of Darbasiyeh.

Hala Abdullah: 'I believe in cinema as a means of resistance’

11 June 2021

Wael Sawah: 'I sacrificed literature for politics'

26 May 2021

The following winter, the security officers’ visits increased. It was very cold, and the officers raided her house every four days. Sultana used to count the days like this: one, two, three, four—today is raid day. She didn’t know where her husband was. He could have been in the mountains, or even the field behind the house. He could have been anywhere.

Sultana could no longer handle the harassment. She told her mother Nuri about it. Nuri asked a relative who owned a truck to help Sultana and her children move to Qamishli yet again. Two men from Amouda came to help the women move. After driving for some time, the truck broke down in the village of Tal Karmeh because of the frost.

Prior to this, Nuri had to obtain the approval of the district authorities to move the house of her daughter Sultana, who was only 22 years old and had already given birth to three children.

The director of security in the village would not let them move before obtaining official permission. Things were tense at the time. The Baathist government was beginning to plan and implement the so-called “Arab Belt” project extending along 250 kilometers of the Syrian-Turkish border, with a depth of 15 kilometers into Syrian territory. The goal was to separate Kurdish people on either side of the border from one another. Kurds in the area called the border the “line,” after the former railway line that formed the border between Syria and Turkey and separated families when it was built—there were the families from “above the line” and those “below the line.” As part of the Arab Belt project, the Syrian government brought in ethnically Arab families, most of whom were from nearby Raqqa, and established settlements for them to occupy Kurdish-owned farmland. Some 120,000 Kurds were deprived of the rights associated with Syrian citizenship, including education and medical care, as they were a “people without a history, a civilization, language or ethnic origin, and are distinguished only by force and violence,” according to a report written by Muhammad Talab Hilal, the head of the political police unit in northeastern Syria at the time.

In the 1970s, the Syrian government sent more than 25,000 Arab farmers whose lands were flooded after the construction of the Tabqa Dam to live in the Arab Belt. The government built 33 villages—or housing units, as they were called—to accommodate the newcomers, equipped with water, electricity, schools, roads and police stations, while existing Kurdish villages were deprived of such services. This was in addition to a policy of Arabization that saw Syrian authorities change the original Kurdish names of local cities, towns and villages to Arabic names. It was also forbidden to give Kurdish names to newborns.

The goal was to separate Kurdish people on either side of the border from one another.

When Sultana used to tell us about all this, she remembered all the numbers and dates. She’d tell us that whoever tastes injustice cannot forget it. These events are an integral part of Sultana’s story, this injustice that Syria’s Kurds have inherited from generation to generation.

The truck broke down in Tal Karmeh because of the frost. Someone needed to pour hot water over the engine so it could get moving again. They asked for gas and some water from people in the village but the residents were afraid to help. In those days people were afraid of everything—that included helping strangers on the road, for fear that this would make them wanted by security forces.

For example, during one of Sultana’s many moves, she built her own mud house without help from anyone else. Nobody dared help the wife of a man wanted by security. Alone, she transported wheat, made bread, fetched water and cared for her children.

Long night to resurrection

05 February 2021

Mending what has been broken

12 February 2021

Sultana’s story is part of my own. I don’t mean to say that the story belongs to me per se, but it’s a part of my memory, despite the fact that I didn’t live through it myself. It is part of my family, part of myself. My grandmother Sultana used to tell us these stories every time the electricity cut off and we gathered together in the dark. She talked and talked and talked without getting tired of the words. She was afraid that the story would be lost, and we’d be lost with them. These stories formed me, until I started to feel that they were my own stories, as if I myself could recognize the face of the security officer as he took the baby from Sultana’s hands and threw him to the ground. I could make out the smell of the soldier who kicked her face. This is a part of my memory, the memory of the Baathist state.

To return to Sultana’s story: the truck broke down in Tal Karmeh. When they lost hope that residents from the village would help them, they had little choice but to unload the family’s belongings so that they could find her gas cooker, which happened to be stowed deep within the truck behind everything else. One of the drivers fetched water from the river nearby, which they heated up on the cooker. This is how they solved the problem and finished making their way to Qamishli.

At first, she rented a house in the Hilaliyeh area. At the time, Hilaliyeh was located along the border with Turkey, outside of the city and surrounded by fields on all sides. It was not easy to obtain drinking water in the town, which expanded over the ensuing several decades and became part of Qamishli city. However, only two months after moving to Hilaliyeh, Sultana found a home in the Ashi Buzi area, living in that house for only three months. Afterwards she returned to her old home in the Qodorbak neighborhood.

Sultana lived in Qodorbak until Saddam Hussein’s 1974 coup against the autonomy agreement for Kurds in Iraq. She had six children. Until then, at the beginning of each summer, she used to visit her husband in the mountains of Iraqi Kurdistan, with her children in tow and with the help of the Peshmerga. She’d stay there for three months before coming back home.

When Sultana used to tell us about all this, she remembered all the numbers and dates. She’d tell us that whoever tastes injustice cannot forget it.

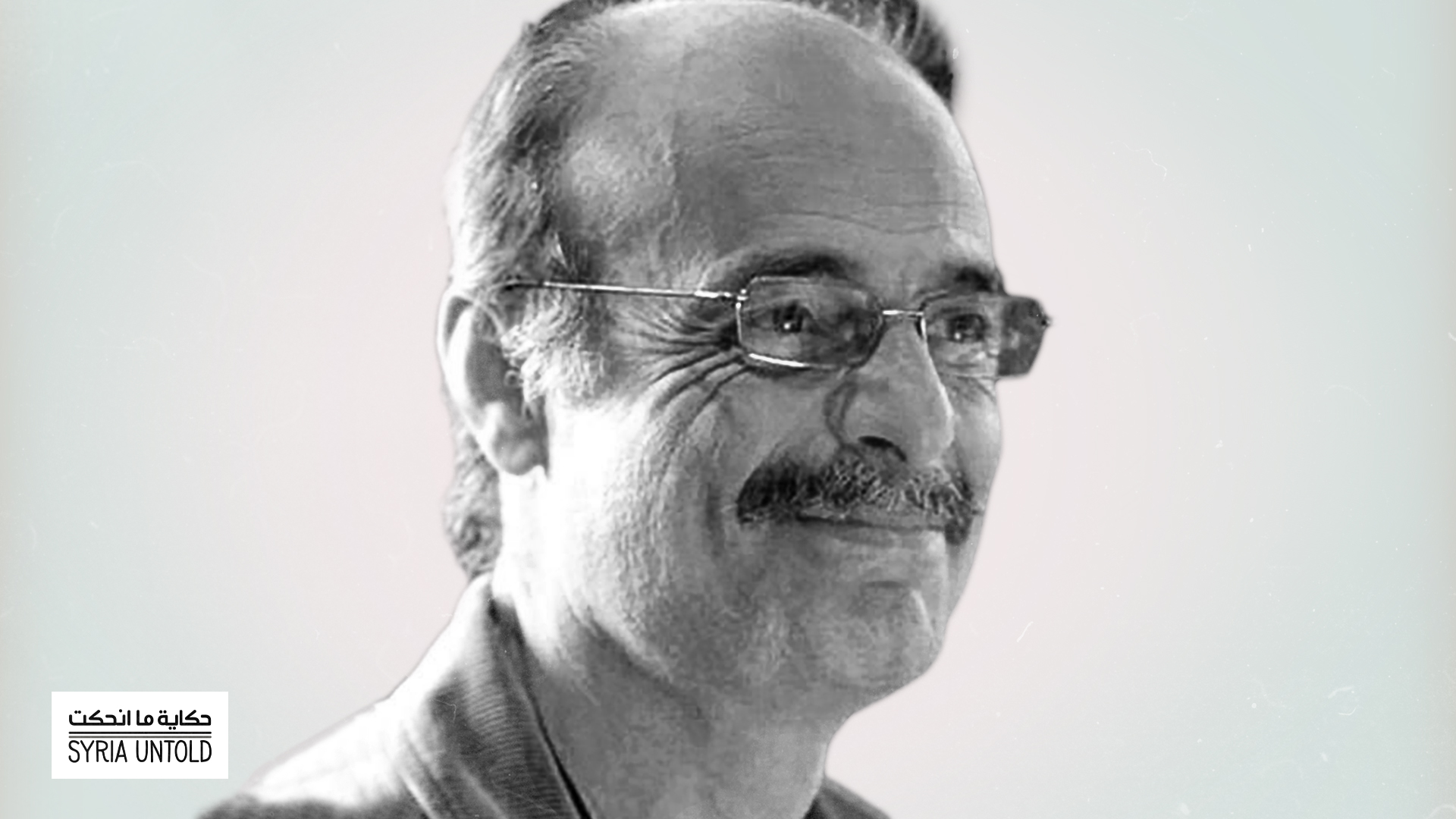

Sultana’s husband, my grandfather, served in the ranks of the Kurdish revolution. Mustafa Barzani’s revolution. My grandfather was a peaceful man. He did carry a weapon, but he didn’t like fighting, so his duties were limited to helping journalists and securing clothing, food, water and other supplies. We had a picture of him standing next to Iraqi president Jalal Talabani. Actually, there were three men in the picture: my grandfather on the left side of the photo, then a man whose name I forgot, and in the middle is Talabani. Snow covers the ground. They are wearing Peshmerga clothing.

After the signing of the Algiers Agreement between Iran and Iraq, it was announced that the autonomy agreement that had been made five years earlier between Barazani and the Iraqi government in Baghdad was cancelled. This is how they announced that the Kurdish revolution had failed, like all other Kurdish revolutions before and after. Should I talk about all the failed Kurdish revolutions, the ones we used to tell stories about in secret, in our homes? Should I talk about the Sheikh Saeed revolution, the Dersim rebellion, the Barzanji revolts, the 2004 Kurdish uprising in Syria, the last of which I witnessed myself? Maybe another day.

It was 1975. The failure of the Kurdish revolution had just been announced, and my grandfather heard that the Netherlands was prepared to receive 740 Kurdish families, that he and his family could go too, if they wanted. But my grandfather refused, believing that this move would do more harm than good to the Kurds and the fight for their rights.

A famine, a ship and a folk song that spanned borders

18 December 2020

Returning to Abu Alaa al-Maari in our year of plague

13 May 2021

And so he returned to his family in Qamishli. But the Syrian security forces were waiting. There was constant surveillance and questioning almost daily. He decided to move with his family to Damascus, where he found work selling used clothing from a mobile stand in the Marjeh Square area of downtown. Then he rented a dukkaneh, a convenience store, on Revolution Street, which is where we all grew up.

In Damascus, they summoned my grandfather for security questioning every week, despite his retirement from political work. He told them that the Kurdish revolution had failed, that now all he wanted was to raise his children. But they kept summoning him, eventually placing him under house arrest. He was banned from leaving the country without security approvals that were difficult to obtain. He managed to leave Syria only twice after that, and only with the help of many intermediaries, many complications and endless investigations. He died in 2007, sent off by a grand funeral in Qamishli held out of respect for his history of resistance.

Before all that, their house in Damascus was on the highest hill in the Kurdish part of the Rukn al-Din neighborhood. They didn’t have the money to rent a house anywhere else. It took half an hour to climb up to their house by foot, climbing because the cars couldn’t get that high up.

As Al-Mullah continued to work, the family found a sense of relative stability. Their financial situation improved a little. Finally, they were able to buy a two-room house on the hill, at a lower altitude than the old one. They were nine people: seven children, Sultana and her husband. And yet the house was never without guests. When it rained, the house would flood. They lived there for five years, until they were able to buy a plot of land closer to the main road. The clothing business turned out to be profitable. And so they bought some land with one of Al-Mullah’s partners, a spot where the houses of the hill used to throw their garbage. They cleaned up the plot of land and constructed the building that they came to live in. That’s where I was born.

After years of working in the second-hand clothing trade, washing, ironing and selling clothes, the municipality banned the sale of used clothing in 1996. Years later second-hand clothes returned to the streets, but by then my family’s luck had run out.

After 1996, the family went from selling second-hand clothing to selling leather belts, socks and summer clothes. My grandfather’s dukkaneh was still there, and the merchandise changed every two years until the government decided to shutter all shops like it in 2004. The government demolished the shop and the entire market surrounding it, converting the area into an ugly park. They didn’t compensate anyone for the loss. This is how hundreds of families lost their sole sources of income.

Al-Mullah died in 2007. My granfather died in 2007 after visiting Syrian prisons dozens of times. He died after creating a legend for himself one day, among the Kurdish villages, after becoming a story that grandmothers would tell their grandchildren.

Aren’t revolutions explosions in the face of injustice?

One of the stories goes like this: my grandfather and some of his revolutionary friends once attacked the convoy of the unjust qaimaqam, the local governor, and took everything the man had been transporting with him on the way to the town of Derik. The security forces went berserk, arresting all the men in the area without managing to find my grandfather.

Finally they arrested him in the village of Jal Agha, and transferred him to Tal Kojer. There he was tortured so severely that he lost hearing in his left ear. From there they transferred him to Qamishli. He and his companion tried to escape near the village of Jimaayeh, but failed.

But then, while reaching their last point before finishing their escape, my grandfather jumped out of the car and headed towards the Bashiriyeh area of Qamishli. The security forces tried catching up to him, to no avail. He fled to a house, where a woman hid him. She gave him her husband’s clothing and helped him flee towards the Turkish border, hidden in the car of a local Kurdish resident. Security officials later arrested the woman and the owner of the car, as well as many local men, but they were unable to reach my grandfather. He became a local folk hero. People named their sons Muhammad Niou after him.

Lina Barakat: ‘I want to be a participant in this change’

21 December 2020

Within the margins, and breaking free: Syrian cinema

23 January 2021

I write now about Sultana, but why write down her story and return to her time and again, and not simply tell the story of her husband in minute detail? After all, he is the hero, the one people talk about. Isn’t he the one who sat at the forefront of every gathering he attended, the one who lived in the limelight while Sultana remained in the shadows? But I don’t believe everything I see. Sultana was the origin of the story. She was the cornerstone upon which my granfather built his legend. When he was tired, he went to her. She gave him a home when he slept out in the open, the warmth of his blood melting the snow. Sultana is the origin of our story and her husband did nothing but search for the meaning—the meaning of his life, his idea of a supposed homeland. He didn’t understand the value of what she gave him until the final days of his life. He wanted to finally kiss her like he meant it, but she refused every time he tried. She used to say that he was too late, that he should have tried 50 years earlier, 40 years, 20 years, that now there was nothing left for her to do but prepare a comfortable grave for him to rest in eternal sleep.

I do not mean to say that he wasted his life away from her. It is true that I don’t believe in nationalism. But what he fought for wasn’t exactly nationalism—he fought against injustice. That’s how I see it. If the revolution was a nationalistic one then so be it, but injustice is what pushes people to revolution in the first place. If the Kurds weren’t oppressed, they wouldn’t have started a revolution. Aren’t revolutions explosions in the face of injustice?

For 15 years, she alone received the beatings of the security officers and faced their questions and investigations almost daily, before moving to Damascus. She was under threat her whole life. I remember the security agents coming to our house in Damascus up until I left Syria in 2011, coming weekly to ask her their stupid questions. How many children do you have? What are their names? Since when have you lived in Damascus? Every week the same questions. The older family members in the house would hide the children—my siblings, cousins and I—every time a stupid security agent came with his big notebook.

One of the agents, the one who came to our house most frequently in those last years, looked like an intelligence agent you’d see in the movies. Big belly, big notebook and stupid questions as if idiocy dripped from his face. We’d eavesdrop from a hole in the door, while the rest of the family feared one of them would say the wrong thing, something the idiot would write in his idiotic notebook, and then they’d disappear into prison for years.

Sultana had no friends her age when she was young. She used to tell us it was better to associate with older people. The elderly protect against a bad reputation, while the young bring unsavory companionship. One of the women would tell a joke about their husbands, and one joke would lead to another. Then Sultana would mention her own far-off husband, and the people would forget the jokes and remember what the wife of the revolutionary politician said. She always saw herself as beneath others, with regards to happiness, jokes and laughing. They all had men and all their children had fathers, except for her and her children. She did everything on her own and lived alone. Maybe that’s why she had so many children. Did she give birth to them for her own consolation, or because her husband wanted many children to tell his story?

One time I asked her, when she was finished telling one of her stories that she told a thousand times, if she was satisfied with how her life turned out. She replied that she spent her entire life tired and oppressed but with dignity and a good reputation. She emphasized the word dignity. She said that whoever has no dignity has no meaning in life, that people remembered her as a good woman and nobody said anything bad about her. She was content.

A landlord once evicted her from the house she rented. Well, he didn’t exactly evict her, but he told his wife that he was tired of all the mukhabarat investigations and constant security visits. The wife relayed this information to Sultana. She couldn’t bear this sentiment, so she left the house three days later without saying a word, and found another one-room house to rent. It was a sentence that changed the details of her endless life.

Sultana used to tell us after every story that she had forgotten everything. She told us her life had been one long, unending torment, but that despite everything, she loved my grandfather. She loved him and endured everything for his sake, though she was ashamed of him in her youth. In those early days, their relationship resembled that of a father and daughter. He was 13 years older than her. She felt shy around him, embarrassed by his dominant presence. The big man. The hero. The legend. Later, when they settled in Damascus the two became friends. They talked about everything. He started taking her to the cinema, where she found a magic that transported her to other places. She learned that there was a bigger world than the one she could imagine, that life itself was far more expansive than she ever thought. She could remember Omar Mukhtar’s film as if she was still seeing it in front of her eyes. Sultana loved, despite the difficult and rather restricted life she lived within a vast world. She wanted to open her eyes to this world. She couldn’t do this herself, so she made her children into her eyes. Sultana made herself go hungry so she could send her children to school. She wanted them to learn, to grow up and see the world, to live better lives than the one she lived. She wanted her children to be philosophers. She always used to tell us this. She wanted them to be eyes for her and other Kurdish people.

In the last years of her life, Sultana lived in Qamishli with her daughter. She’d visit the empty house in Damascus whenever she had the chance. Her house, which throughout the years was filled with guests and food, fell quiet and dusty after her children and grandchildren left. She used to tell us she never felt at ease except in that house in Damascus, that the house was her homeland.

She’d often repeat the Kurdish saying, “Damascus is sweet as sugar, but the homeland is sweeter.” I’d ask her, “Where is your homeland?” “Here, this house is my homeland.” “But this house is in Damascus,” I’d say maliciously. She’d respond, “Damascus is my homeland.”

Sultana died in Qamishli on the first day of 2020. She was buried next to her life partner, her husband and sweetheart, my grandfather Al-Mullah Muhammad Niou.

When we received the news, I was gathering with my siblings, father, daughter and partner in a small city in eastern France to celebrate the new year. It was the first time we had all gathered together since 2004, the year my older brother fled Syria. A day later, my daughter had to go to the hospital with a terrible virus. She stayed there for six days, the most difficult days of my life. It wasn’t easy watching the machines count her breaths and heartbeats all day and night.

I didn’t have time to properly grieve for Sultana. I became occupied with my sick daughter, and my life in exile that I still can’t master. A long time has passed since Sultana’s death. Maybe now I can mourn my grandmother, and dedicate this text to her as I tell part of her story to strangers who never knew her.

They said that she slept the night before her death at the home of one of her relatives in the Hilaliyeh neighborhood. She woke up early and walked to her daughter’s house, complaining of chest pain and asking them to take her to the hospital nearby. She died before reaching the hospital, aged 77 hardened, tired years.