BEIRUT: Mahmoud al-Kanu feels uneasy looking up at the 25-story apartment building where his family used to live. The high-end tower charred into a skeleton a year ago when tons of poorly stored ammonium nitrate exploded, devastating parts of Beirut and taking more than 200 lives.

Mahmoud’s 15-year-old sister Sidra died in the blast; his parents and 11-year-old sister suffered serious injuries.

For Mahmoud, as for other victims’ loved ones, this has been a year of grappling with grief, as well as rage for the lack of accountability towards Lebanese officials who for years let more than 2,700 tons of lethal explosive material sleep at the heart of the city.

The August 4 blast killed 218 people, injured 7,000 and displaced 300,000 from their homes. It damaged half of the city, causing $3.8-4.6 billion in material damages according to the World Bank.

Among the dead were dozens of Syrians. One year on, some of their families say they feel especially hard hit, oftentimes overlooked in the ongoing aid response to the explosion. All this comes amid an unprecedented financial crisis in Lebanon that has worsened access to everything from electricity to gas and basic medical supplies.

From Aleppo to Beirut, cities burning

26 February 2021

My childhood friend, now a ghost

18 September 2020

A few days before the one-year anniversary of the Beirut blast, Mahmoud revisits the building where his father worked as a concierge. Despite the few repairs in the façade, it still has the feel of a crime scene. It’s the first time he has returned to this area.

“After the blast, I felt a sort of hatred for living in Beirut,” says Mahmoud. His family, originally from Aleppo, moved to a coastal town south of the Lebanese capital after last year’s explosion. Mahmoud and his brother now work in a beach resort.

The family left behind Beirut, but not their hospital bill. The several weeks that his parents and sister spent hospitalized translated into a debt of $3,500 plus 25 million LBP (roughly $1,200 at the current market exchange rate).

His father suffered a skull fracture, lost sight in one eye and lost hearing in one ear. His mother underwent two surgeries for her fractured back and foot. And his 11-year-old sister Houda had a titanium plate implanted on her neck; it allows her to turn her head to a certain degree, but not fully.

A therapeutic corset from the NGO Basmeh & Zeitooneh and two months of rent covered by Save the Children: that’s all the aid Mahmoud’s family has received in the aftermath of the explosion. He registered as a refugee at UNHCR following the blast but says he has yet to receive any assistance.

Mahmoud’s salary from the beach resort is only 1 million LBP (around $50 at the current exchange rate), barely enough to cover the family’s 800,000 LBP monthly rent. “With the 200,000 LBP left over, that money is enough for two days, then comes the debt,” Mahmoud says with a tired smile.

Remembering Sidra

A big photo of Sidra smiling hangs in the family’s living room. “That photo is the first thing you see when you enter our house, and it’s the same one I have on my phone,” says Mahmoud, showing his sister’s smile on his phone screen.

His mother doesn’t talk much about Sidra, “to avoid crying and keep the morale of the family high,” Mahmoud says. “But we need to talk about her.”

“We cannot forget,” he adds.

“Every day, there is a moment of sadness and tears. At any family dinner, when we drink coffee together, we feel Sidra’s loss. We feel her absence and her tenderness,” he says.

The loss has taken a psychological toll on the family. Mahmoud and his younger sister Houda haven’t been able to sleep in the last few months. Sometimes he takes antidepressants, now increasingly difficult to find across Lebanon due to medicine shortages.

Mahmoud has found some comfort among other victims. He met a young girl who lost an eye in the explosion. “There is moral support among us. For example, I lost my sister, and that’s a disaster. Maybe if you lose your eye, it is kind of ‘less bad.’ We comfort each other like this.”

‘My house feels empty’

Dressed in black, Mona Jawesh drinks coffee in her living room. In the corner, a collection of photos of her daughter Rawan stares at her back. On August 4, Rawan had just finished her shift as a restaurant server in the Mar Mikhael neighborhood when the explosion erupted. She didn’t survive. Mar Mikhael, located just south of the port, was among the areas hardest hit by the blast. Rawan was 20 years old.

“When I see her photo, I cry. I want her, not her photo. My heart burns,” says Mona, originally from Aleppo. She came to Lebanon more than 20 years ago and raised her children here.

Mona remembers her last conversation with Rawan. Two days before the explosion, Rawan didn’t go to work due to COVID-19 restrictions, but she was called to work again on August 4. “Why do you have to go to work today? Two days ago, there was corona and now there isn’t?” Mona recalls asking her. Rawan laughed and brushed it off. She had planned to work that day and the following, and then hold a belated birthday celebration at home. She had turned 20 years old just a few days before the explosion.

The year since then has been difficult for Mona. “My house feels empty, my life has been engulfed in darkness,” she sighs.

Rawan aspired to be a film director and had already gotten some acting gigs. “Rawan was my most precious thing,” Mona says. She and Rawan used to drink coffee together and listen to Fairouz while planning imaginary travels. “We would open Youtube and she would ask me, ‘Where do you want to go today? Australia, Istanbul?’”

“Rawan was glued to me. It is impossible that she was taken from me in just a second. I cry about her day and night; I will never forget her,” Mona says.

“Sometimes I feel like she is not gone. I feel like maybe she is travelling and she will come back. I still hear her voice sometimes.”

Mona, her son and her daughter have suffered nervous breakdowns since the loss of Rawan. “I have to take care of my son and my daughter. I have a family. I can’t shut down, I need to be strong,” she says.

At any family dinner, when we drink coffee together, we feel Sidra’s loss. We feel her absence and her tenderness.

Mona has found some strength in the protests led by the families of the other victims. Throughout the past year, the families have demanded accountability for those responsible for neglecting the dangerous ammonium nitrate that led to the blast. Mona says she never misses any protest or sit-in. “I don’t want my daughter to be forgotten. I am her mother. If I don’t fight for her, who will?”

But a year after the explosion, the Lebanese judicial system has yet to hold anyone accountable.

Syria’s lucrative detainment market: How Damascus exploits detainees’ families for money

13 April 2021

‘Little Syrias’ in a big world

26 July 2021

Among those responsible are high-level government officials, including President Michel Aoun, who were warned of the explosive material yet took no action to mitigate the dangers. A Human Rights Watch (HRW) investigation released on Tuesday compiled evidence of “omissions and actions by officials that, in a context of longstanding corruption and mismanagement at the port, allowed for such a potentially explosive compound to be haphazardly stored there for nearly six years.”

“Instead of taking responsibility, government officials have used every tool in their book to try to escape accountability,” says Aya Majzoub, Lebanon researcher at HRW.

Families like Mona’s are left to deal with the aftermath. For three months after the explosion, Mona and her family requested psychological support from a number of NGOs in Beirut. Her daughter “was in a very bad condition.” Mona could not wait to seek free treatment, so she took her to a private clinic. Later, an NGO offered therapy sessions free of charge by phone.

Mona’s daughter “reached a point where she didn’t have the strength to come with me to the protests of the families of the victims,” says Mona. After starting therapy, her daughter decided to rejoin the protests. On the first anniversary of the explosion, Mona says she knows where she will be: protesting in the streets.

Scars in the basement

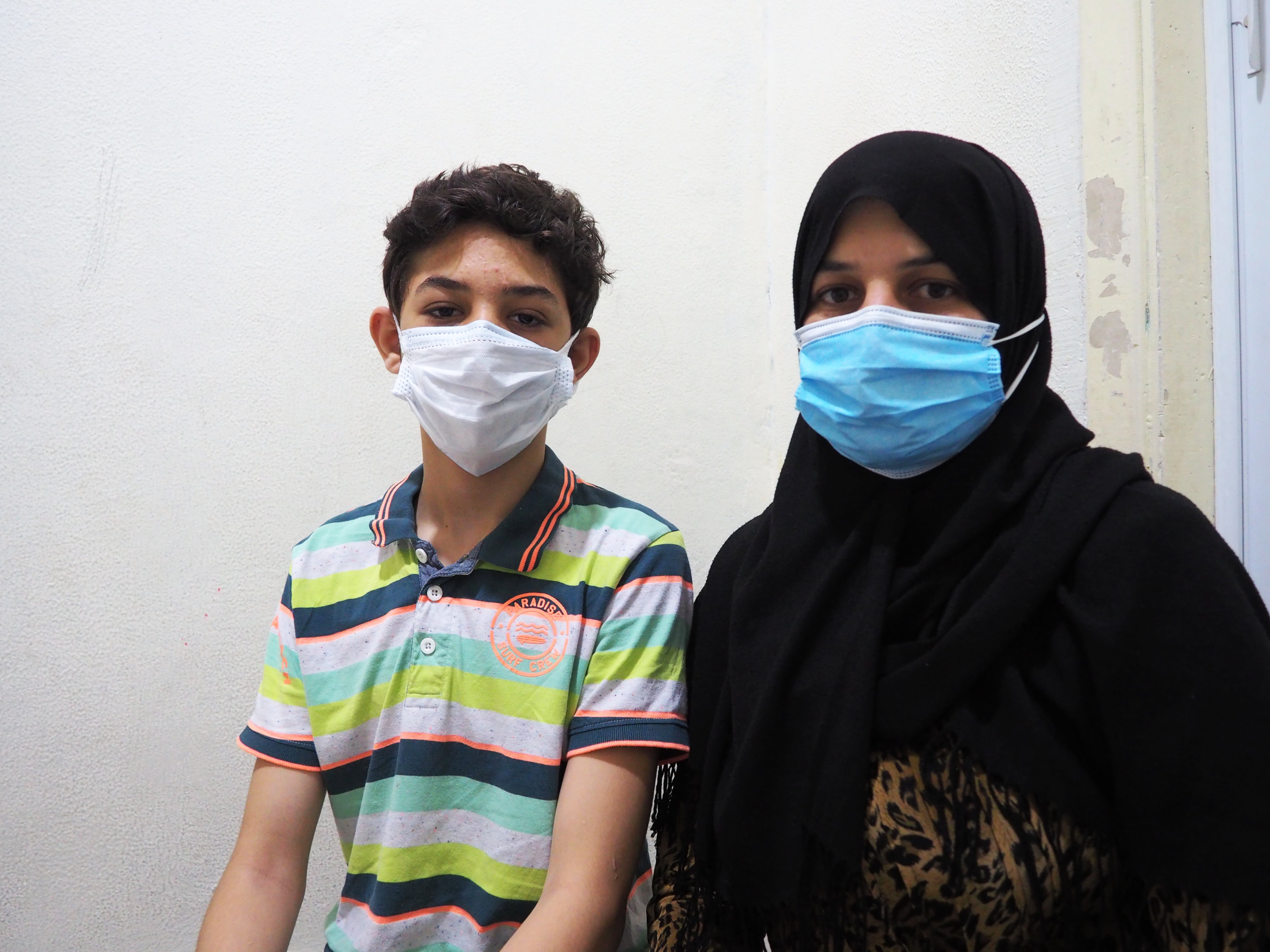

“Will these scars that hurt go away?” This is the question Mariam Muhammad al-Ahmad most often hears from her 13-year-old son Mousa. She doesn’t have an answer.

The explosion blew away a door frame in their family’s home in the Geitawi neighborhood, injuring Mousa in the head. “He constantly looks at himself in the mirror to see if the scars are gone,” Mariam says.

Mousa lost hearing in his left ear and partially lost sight in one eye. “He can’t bear the sun. When he walks in the street, he gets dizzy and tired, and his scars still hurt,” Mariam explains.

Mariam cannot afford to take Mousa to a specialist doctor. “I don’t have the economic means to enter a private hospital, so I went to primary healthcare centers, which are cheaper,” she says.

In theory, UNHCR is meant to cover up to 75 percent of the hospital bill for Syrian refugees in Lebanon. But Mariam says all the hospitals she visited asked her to make payments she could not afford.

Throughout the Beirut post-blast response, under the umbrella of the UN-led “Lebanon Flash Appeal,” $167 million landed in Beirut. Food assistance targeted 300,000 people and 24,000 out-patient consultations were provided, per OCHA data.

These figures mean nothing to Mariam. “In the news, they say aid is coming for everyone in Lebanon, but where is the money?” she asks.

Mariam lives with her husband and their three children in a windowless basement in Geitawi, a hilltop neighborhood less than one kilometer from the port. An NGO rebuilt their ceiling and fixed the front door free of charge. She tried to register in several organizations to obtain food or rent assistance, to no avail.

“All the NGOs told me they already took enough names and can’t help anymore, or that they don’t register Syrians because Syrians are covered by UNHCR,” she says. UNHCR largely suspended the registration of Syrian refugees in 2015 per request of the Lebanese government.

The Lebanese army distributed food baskets in Mariam’s building, with the exception of her family; they told her they didn’t help Syrians.

Mariam’s family originally comes from Ras al-Ain, a town in northeastern Syria. Though registered as refugees with UNHCR, they do not receive cash assistance and their resettlement request languishes. “Every time I call UNHCR, they tell me ‘we are studying your file.’ It has been three years [since we presented the resettlement request]! How long does it take to study my case?”

If I could, I would erase August 4 from the calendar with my own hands.

Her husband, a day laborer, earns 600,000 LBP (about $30 at the current exchange rate) monthly. Their rent is 500,000 LBP. They have precious few hours of electricity per day. “When the electricity is out, I have to open the door to breathe because I don’t have windows,” Mariam says, pointing to the water droplets condensed on her walls. “My son has asthma, he is always coughing ...dogs live better than us.”

A year on, the psychological wounds of the blast still resound. “I am psychologically tired. I feel constantly under pressure, like I’m suffocating. Sometimes I scream at my children,” says Mariam.

She hasn’t gone to therapy, but her children have attended some psychosocial support activities. Mariam’s youngest son suffers from bedwetting and the eldest has recurrent nightmares of something falling on him, or himself falling. The whole family gets startled whenever there is a loud sound.

“If I could, I would erase August 4 from the calendar with my own hands,” she says.

Victim’s rights only in ink

Victims of the explosion and their family members are entitled to the same economic compensation as soldiers martyred in the Lebanese army, according to Law No. 196/2020. Those who sustained a permanent disability—some 150 people according to several NGOs—are entitled to health benefits for life via the National Social Security Fund.

“The state is supposed to cover the cost of the medical treatment for people who sustained permanent disabilities, but it is not [doing so],” says HRW’s Aya Majzoub.

“Law 196 is just ink on paper,” adds Nabila Ghsain, a researcher at Legal Agenda, an NGO in Beirut. The Lebanese government’s High Relief Commission is meant to provide financial compensation to the families of the victims—both Lebanese and foreign. So far, 113 families benefited, though only two of them were Syrian, says Ghsain. “Most of the Syrians are not able to bring the official documentation needed in order to benefit from this help. They are still working on getting these papers,” she adds.

Neither Mariam nor Mahmoud have received information about these mechanisms to get compensation for their losses or cover medical costs. Mona applied for compensation, but has yet to receive a reply. “The cost of gathering all those papers from Syria and from here, the lawyer fees, going to the embassy…at the end I paid more to get the documents than what I would get from the compensation,” she says.

Seeking justice

The Beirut blast “was the result of consistent negligence and incompetence by state officials,” says Majzoub. Such neglect, she adds, constitutes a “violation of the right to life.”

In a joint letter released this past June, 53 organizations denounced the Lebanese authorities for political interference and obstructing justice. Ex-ministers and high-ranking security officials appear shielded by judicial immunity, despite the attempts of the judicial investigator to charge them.

These organizations asked the UN Human Rights Council (HRC) to establish an investigative fact-finding mission to assess the responsibilities of the blast.

“We would need a state or group of states to put forward a resolution in the HRC establishing a fact-finding mission,” but “nobody yet has signaled a willingness to lead,” explains Majzoub. The next opportunity to present this resolution will be in the HRC’s September’s session.

The findings of an international fact-finding mission could be used at three levels, according to Majzoub: firstly, for “targeted sanctions against those found to be responsible.” Secondly, in the Lebanese judiciary: “once you have a UN document establishing responsibilities, it will make it much harder for the Lebanese judiciary not to prosecute all those responsible.” And thirdly, in the courts of the countries of origin of some victims. For instance, French and German courts have opened investigations, so the hypothetical findings of a fact-finding mission “could be used in criminal prosecutions abroad and those courts could issue international arrest warrants against individuals they find guilty,” Majzoub says.

“Where is justice? After one year they don’t know where the people responsible for the blast are? They are all liars,” Mariam says, speaking in her basement apartment in Geitawi.

Mahmoud feels similarly discouraged. “I have no trust left on this trial; but if there’s no justice on earth, there will be justice in heaven,” he says.

“We hope to get justice and to know who perpetrated this crime and who took our children,” says Mona, Rawan’s mother. She still finds it difficult to comprehend how on that fatal day, after a fire broke out in the port, those who knew that explosives were stored there didn’t order the evacuation of the area.

“My daughter was taken from me,” Mona adds. “They killed her, this is a crime. I will never be silenced.”

Editing by Madeline Edwards