In 2012, a year into the Syrian uprising and growing violence in their country, a group of young Syrian comics artists decided to gather their voices together. They kept their work anonymous in order to comment on war, politics and society through their comic strips. The result was the online collective Comic4 Syria.

The decision to establish a collective devoted solely to comics is not peculiar to Syria. In the wake of the Arab Spring, many such collectives appeared throughout the Arab world. But what distinguished and sustained Comic4 Syria is the sheer length of Syria’s war and the everyday horrors of the past decade—all depicted within the strips and panels posted to Comic4 Syria’s Facebook page.

The past 10 years have seen a wave of images emerge from Syria, whether photographs of fighters and gas queues, cartoons, cell phone videos of mass protests, illustrations or paintings. All things visual have played a crucial role in the conflict, as pictures of Syria circulate globally and become the heart of competing narratives.

From Ottoman Syria to Argentina

02 August 2021

What did exile change in our narratives?

26 January 2021

In this climate, comic strips created and published by Comic4 Syria and others erupted with urgency. They portrayed the euphoria of street protests, the casual brutality of Syrian prisons, and everything in between. Perhaps they were one attempt to compile the fleeting “now” and “here” against the backdrop of an ever-pressing and competing series of events. And though Comic4 Syria stopped publishing in 2016, its comics still serve to narrate or document a certain moment in the history of Syria’s revolution. They are an archive for the future.

What, then, can survive as a repository of the “now” and “here”? What legacy do these comics give to the future? And how can we single out comic strips in an atmosphere already over-saturated with visuals?

Censoring comics

In the mid-1990s, researchers Allen Douglas and Fedwa Malti-Douglas were the first to write a scholarly book on comics in the Middle East, mostly focusing on political cartoons. Syria in particular, they wrote, had a deep history of censorship:

“Syria, virtually alone among major Arab states, blocks the entry of other Arab [comic] strips, creating its own monopoly of images. […] Nowhere in the Arab world does a government so effectively control the comic strips as in the Syrian Arab Republic.”

Comics in Syria had long been the domain of children’s literature, an arena where propagandists competed over molding the future ideal citizen. Take, for example, al-Tali‘i, the official magazine of the regime’s Tala’i‘ al-Ba’ath youth scouts movement. The magazine has been produced since 1984 and distributed in schools and corner shops. The ideology of al-Tali‘i was clear: Ba’athism, Arab nationalism, Syrian patriotism, militarism, secularism and, at least ostensibly, the worship of science and productivism.

Though Comic4 Syria stopped publishing in 2016, its comics still serve to narrate or document a certain moment in the history of Syria’s revolution.

Al-Tali‘i’s comic strip series, written by Adil Abu Shanab, illustrated by Mumtaz al-Bahra and grandiosely titled “Hasan Muqabba‘a, Hero of the Ghouta” is a notable illustration of this ideology. The strip depicts “martyrs” who died fighting the French between the two World Wars. Members of the resistance are “revolutionaries” comparable to guardians of the Assad regime. Though set in a different part of Syria’s recent history, the success of the Syrian revolution against the French is represented as the triumph of the Ba’ath Party and its youth scouts. Another less ideologically imprinted magazine, though still published by Syria’s Ministry of Culture, is Usama. Also targeted at children, the magazine is politically conformist but has allowed for more viewpoints, especially under editor-in-chief Zakaria Tamer from 1975 to 1977.

Apart from children’s comics, satirical cartoons, which have a much longer history in the region, made appearances during that same period—mostly in Arab newspapers outside Syria or, in later decades, online.

One exception was al-Domari or “The Lamplighter,” Syria's first independent satirical magazine since the Ba'athist regime took power in 1963. Founded by renowned political cartoonist Ali Ferzat in 2000 during the Damascus Spring, al-Domari quickly won an enthusiastic domestic audience, not to mention multiple awards from around the world. Following the death of Hafez al-Assad, the Damascus Spring saw Syria’s social and political spheres become relatively open, allowing for al-Domari to gain readers. It was over rather quickly, though. Frequent government censorship and lack of funding forced the magazine’s closure in 2003. Still, Ferzat has published more than 15,000 cartoons in al-Domari and elsewhere that criticize corruption, bureaucracy, the accumulation of wealth by the elite and other issues.

Questioning ‘exile’

23 July 2021

Returning to Abu Alaa al-Maari in our year of plague

13 May 2021

Reclaiming reality

With the same impulse that drove Ferzat and others, Comic4 Syria worked to counter the legacy of the regime and to reclaim a hold on reality. As they navigated censorship in Syria, their use of Facebook served to “disseminate the forbidden,” in the words of Lebanese comic artist Georges Khoury. Khoury founded the first comics collective in the region in the mid-1980s. Writer and editor Malu Halasa explains in Syria Speaks:

“As opposed to the essentially monolithic propaganda of the regime, the anonymous [online] group Comic4 Syria has spearheaded a growing movement of multidimensional revolutionary symbolism that has encouraged dialogue, debate, free expression and contestation.”

During the several years it was active, Comic4 Syria’s Facebook page garnered nearly 20,000 followers. It represents an irreplaceable creative source of documentation of the war in Syria. The collective, composed of anonymous contributors, explains their endeavor as follows:

“Committed to freedom and dignity, [our] aim is to document events during the revolution as well as the catastrophic consequences of rupture, displacement and dislocation in its aftermath. […] As the name indicates, the comic is the medium of choice to record everything from brutality in prisons, activities at demonstrations and the violence of military interventions. Often emotive, at times ironic, the object is always to tell a story with depth, to hit the mark in as few panels as possible, to analyze the political and national situation of a country and its revolution. Comic4 Syria does not consider itself a collective of the resistance. Comic4 Syria advocates for artistic freedom, believes in a free people and a free nation and will use artistic methods in collaboration with the imagination of the reader to illustrate the truth in bright colours against exaggerated backdrops. The beauty and the art of the comic lies in its ability to reveal reality through exaggeration. […] Our belief, however, that the work we have so far produced goes someway in documenting this history, is nurtured by the artistic and political wealth around us today. […].”

This quasi-manifesto pinpoints the struggle to represent and document everyday reality, a visual reality that becomes an arena of contestation for the legacy it will leave in the future.

How can we single out comic strips in an atmosphere already over-saturated with visuals?

Everyday horrors

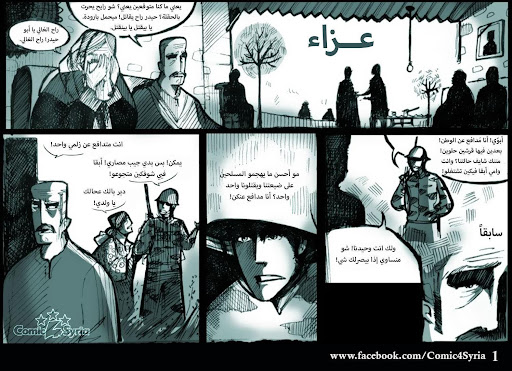

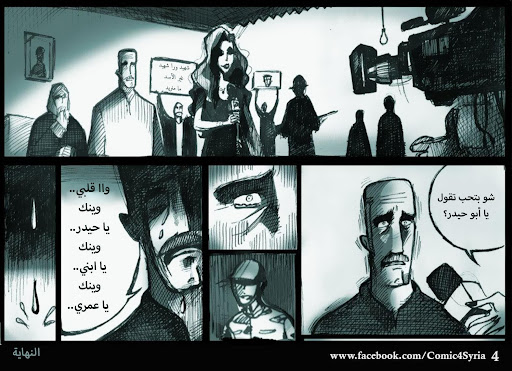

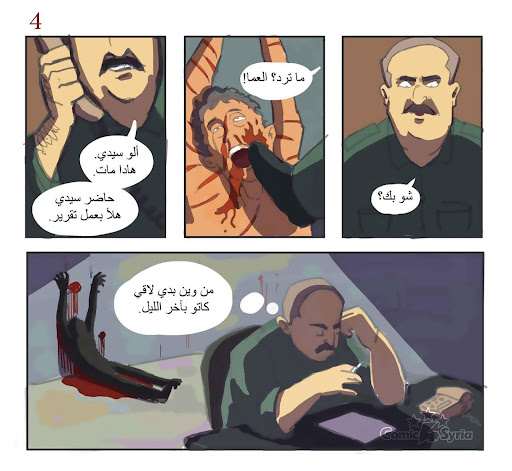

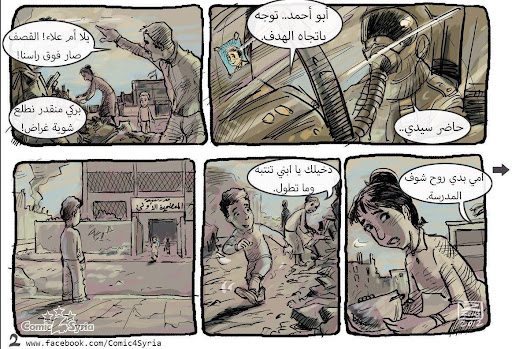

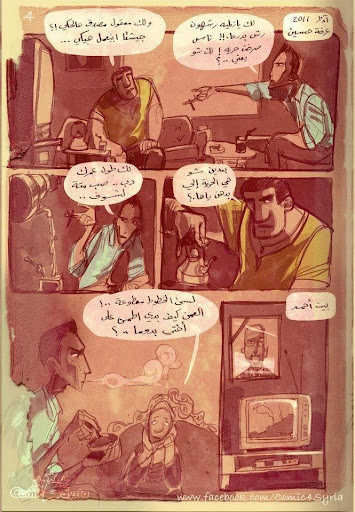

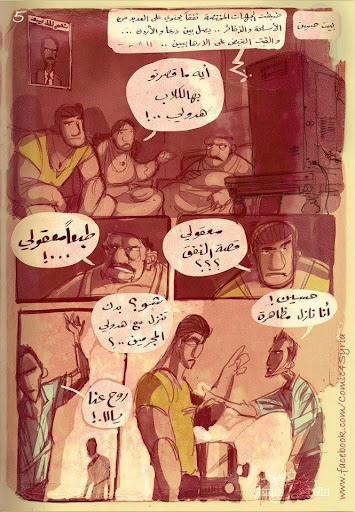

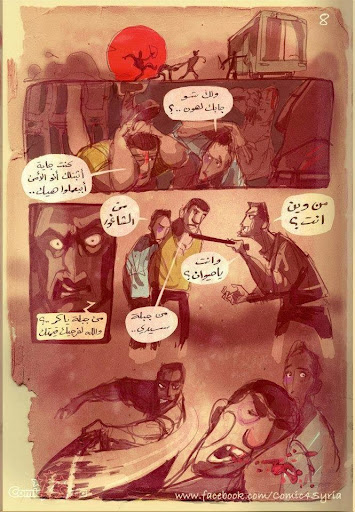

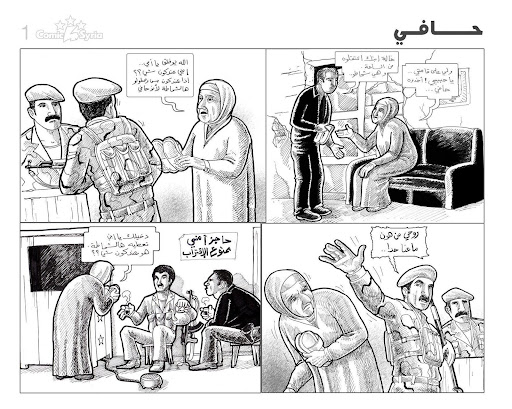

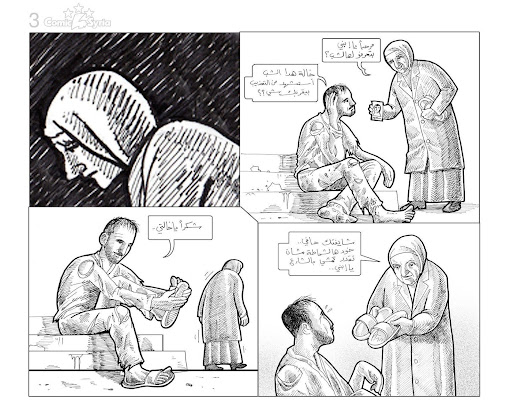

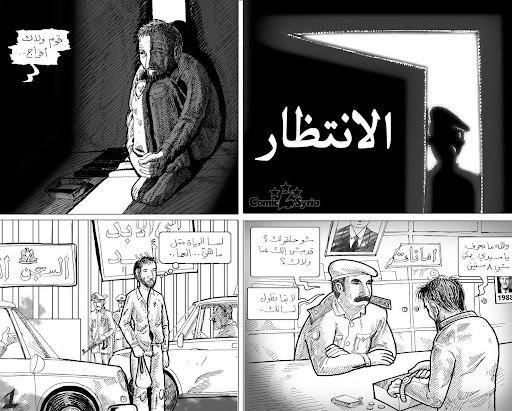

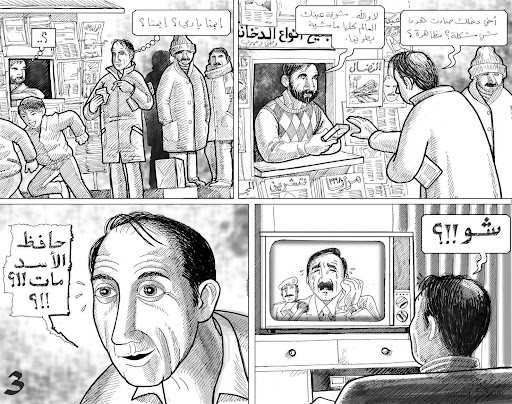

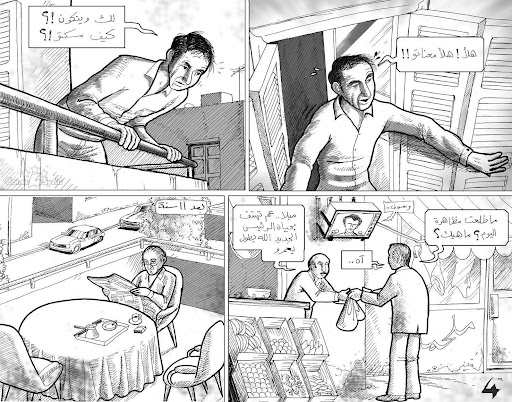

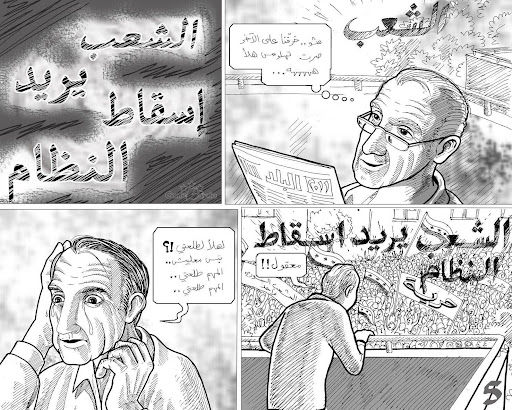

The short comic strips below portray a complex image of the way the war translates into everyday life. As I see it, this is where one of Comic4 Syria’s major strengths lies: in their conscious decision to avoid a Manichean view by refusing to rely on easy dichotomies of good and evil.

The story “Condolences,” shown below, features an only son, Haidar, who comes from a poor village. The dialect of the speech bubbles indicates that he comes from an Alawite family on the Syrian coast. Haidar decides to join the army because he does not want his parents to go hungry, and to defend his village from militants. His father criticizes this choice. When Haidar is killed at war, official regime representatives come to his parents’ house and force them to give a TV interview about losing a martyred son. In the heat of the moment, Haidar’s father is unable to say anything coherent, and instead cries for his dead son.

As Comic4 Syria shares in the Facebook caption accompanying the strip, Haidar’s story draws on real life. Still, in the comments section, some Facebook users criticize the artist for giving nuance to Haidar’s decision to join the Syrian army. The response by the page admins deserves to be mentioned: they stress the fact that these are incidents and stories that take place daily in both Alawite and non-Alawite villages: “بالنهاية هالقصص مؤشر على الشي اللي عم يصير على الأرض. ويا ريتنا كلنا نعطي ادننا للشي اللي عم يصير على الأرض مو اللي عم يجينا اعلاميا. إذا ما صدقت هالقصة جرب تدور على الحقيقة على الأرض”.

The message is clear: these stories are representative of what is happening on the ground and we must lend them an ear.

In the comic strip “Cake,” an interrogator lashes a man with an electrical cable to force a confession out of him. Suddenly, the interrogator’s phone rings. His daughter is on the line; his tone changes to soft and loving. He wishes her a happy birthday, then wonders where he could possibly buy her a cake so late at night. The man under torture interjects that he knows of a pastry place that is open late, a final appeal to humanity that is met with instant death. The final panel shows the interrogator back at his desk, thinking about the birthday cake. The monstrosity of the torturer is reinforced by his double personality, as both a loving father and a brutal torturer. The comic conveys the sense of the banality of evil.

Another uncanny moment is depicted in the comic strip “Mu’dhamiyah” in reference to a suburb of Damascus that was destroyed during the war. Two friends venture out to play in the fields when the father of one, a pilot, is given the order to launch a bomb that kills both boys, including his own.

The comics often tell stories of friends or family members who support different sides of the war, such as in “Cocktail.” The opinions of two childhood friends who grew up together diverge on the events that are unfolding: Ahmad is excited to join an opposition protest, while Hussein tells him the demonstrators are terrorists. Ahmad is arrested following the protest and Hussein appears to defend him. They are both detained for 60 days and their friendship is reinforced upon their release.

“Barefoot” depicts a mother searching every nearby jail for her son, in order to give him the house slippers he lost during his arrest. After a long search, she bumps into a man who informs her that her son has died under torture. She decides to give him her son’s slippers.

Drawn in white and black, and in minute detail, “Waiting” tells the story of a man who spent eight years in prison under Hafez al-Assad. Upon his release, he notes that nothing has changed and he asks the people around him about possible protests. But he’s told that only pro-regime demonstrations are taking place and asks himself: “Until when?”

Upon the announcement of Hafez al-Assad’s death, he opens the windows of his flat exclaiming to the absent masses: “Now! Now is the time! Where are you? Why are you silent?” But once again, he is told that only demonstrations of support to the new president, Bashar, are taking place. Eleven years later, as he sits on his balcony, he hears chants from afar and thinks that he is hallucinating. The comics end with the words: “Did it just happen now? It’s okay, it’s okay, the important thing is that it happened.”

Comic4 Syria’s Facebook page has been inactive since 2016. Nevertheless, through the simple snippets that represent shared and lived experiences of brutality but also of hope, these comics illustrate a human moment that is worth preserving. It is a “here” and a “now,” one with archivable value for the future.

Editing by Madeline Edwards