This report was published in partnership between SyriaUntold and the Network of Iraqi Reporters for Investigative Journalism (NIRIJ).

Read this report in its original Arabic here.

Rima* still isn’t sure whether luck was really on her side.

When Syrian regime forces launched airstrikes on her besieged hometown of Qudsaya west of Damascus, she was one of the first to leave. The town was home to families from the minority Circassian ethnic group, as well as Damascenes and others who originally came from the surrounding areas. Rima’s family is Circassian.

“I was fortunate because the regime allowed some Circassian families to leave, and didn’t force the siege on them as it did with other residents of Qudsaya,” she says. “Still, I realized that maybe this was the last time I would see my hometown, and maybe even my country.”

That was in 2014. According to human rights sources, the aerial bombardment of the town was the first breach of a three-week ceasefire between Syrian regime forces and the local committees responsible for protecting Qudsaya. The latter had been accused of killing a regime officer.

Journalists in northwestern Syria: Between exploitation and displacement

23 September 2021

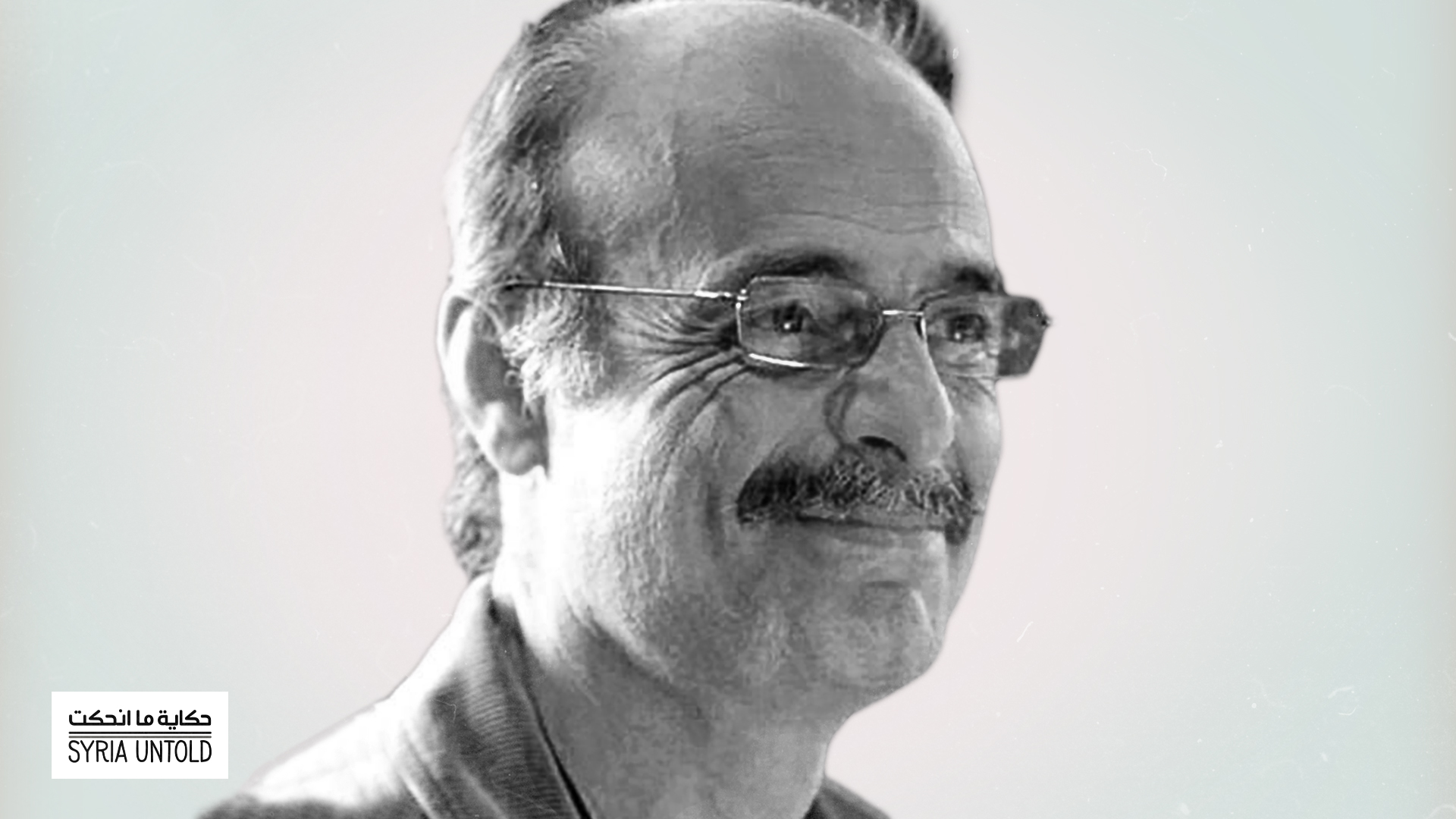

Remembering my friend Bassel Shahadeh

28 May 2021

Rima, now 31 years old, spoke to SyriaUntold from Turkey over WhatsApp. She recalled her family history of migration and displacement, including her family’s displacement from their village in the Golan Heights in 1967.

Her memory goes back even further. Rima recalls the stories her grandmother used to tell about the forced displacement of Circassians, who originally come from the Caucasus Mountains and practice Islam. They fled for safety from a Russian invasion of their homeland in the 1860s, ending up on Ottoman soil. Rima’s ancestors joined the exodus, finding themselves in what would later become the Syrian Arab Republic.

Today Rima and her family rent a home in Ankara, the Turkish capital. She is one of about 15,000 Syrian citizens of Circassian origin who left the country since the war's beginning, according to estimates from 2017.

Their emigration from Syria continues to this day.

A life ‘without problems’

According to historical sources, the first groups of Circassians arrived in Syria in 1860, alongside Chechens and Dagestanis, other groups from the Caucasus who had been displaced to the Ottoman Empire.

They settled down in three main areas in Syria: Damascus and its outskirts (Qudsaya, al-Muhajireen, and the southernmost villages of East Ghouta), Aleppo (Manbij and Khanaser) and the Golan Heights, which was once home to Syria’s largest share of Circassians. That changed in 1967 when the Israeli Army took control of 14 Circassian villages in the Golan, displacing their 18,000 residents. They found refuge in nearby Damascus.

According to Rima, Circassians who still spoke their own language, Adyghe, in addition to Syria’s official language of Arabic, “lived without any apparent problems on the surface, both within society and under the authorities. They practiced their customs and traditions to a reasonable degree of tolerance from the regime, compared with other ethnic groups.”

We used to enjoy the sound of Circassian music that was played in the camp. Every evening, we’d gather together.

This relative equilibrium changed with the outbreak of the Syrian revolution, when the Circassians, who numbered around 150,000 at the time, were divided along political lines: those with the regime and those in favor of the opposition. Some of them began fleeing to Jordan, Turkey and even to the land of their ancestors, in the Caucasus Mountains straddling Russia and Europe.

From Ottoman Syria to Argentina

02 August 2021

Returning to Abu Alaa al-Maari in our year of plague

13 May 2021

'Guests' in Syria?

Sumayya* is 39 years old and has three children. Originally from Qudsaya, she is among the Circassians in Syria who chose to side with the regime. “Since the beginning of the crisis, divisions began showing in my family, between loyalists and those who were pro-opposition,” Sumayya says. “My family remained neutral, following instructions from my grandfather, like many other Circassian families. But I was a supporter of the Syrian state and I’ve written more than once on my personal [social media] accounts in support of President Assad.”

According to Sumayya, Circassian family elders and local notables often try to control the mentality of the younger generation. They want to encourage “returning to the homeland, to the Caucasus, and raising sons and daughters as if they are guests in Syria,” says Sumayya. “They are not to interfere in Syrian affairs.”

However, Sumayya rejected her own grandfather’s instructions, just as she hesitated, at first, to be interviewed. She soon changed her mind, deciding she wanted to talk about the house that she left behind in Qudsaya, as well as the memories it contained. Her grandfather’s “neutral” stance and her own pro-regime stance did not prevent the war from reaching their home. “When the Syrian regime besieged Qudsaya with the aim of expelling militants, I decided to leave with my husband and children and go live in my in-laws’ house in Mezzeh.”

Ali*, who is from the town of Bariqah south of Damascus, has a very different story.

I feel Circassian. I’ve mastered the Circassian language and I keep their customs and traditions.

“In late 2012, there started to be fighting between the regime and FSA fighters, who had taken up positions in Bariqeh and Bir Ajam,” he remembers. “When the bombing intensified, we stayed in the bomb shelter for 11 days. Then I fled with my family to Masaken Barzeh in Damascus and stayed in my sister’s house.” A few months later, regime forces detained Ali for 45 days. He still doesn’t know the reason. They released him as part of a prisoner swap between the regime and FSA in September 2013.

Ali’s case is similar to that of Muhammad, who is 38 years old and now lives in Belgium. Muhammad was born to an Alawite father and Circassian mother but considers himself Circassian. “I feel Circassian. I’ve mastered the Circassian language and I keep their customs and traditions,” he says.

Muhammad was arrested in early 2011 for being pro-opposition. His father, a mukhabarat officer, was able to pressure his release one week later. This didn’t stop Muhammad from attending more demonstrations. He participated in the funeral of pro-opposition film director Bassel Shahadeh and a protest dubbed “Stop the Killing, We Want to Build a Homeland for all Syrians.” For a second time, Muhammad was wanted by security forces. So he fled to Marj al-Sultan, a majority-Circassian town outside Damascus in the East Ghouta suburbs.

Long night to resurrection

05 February 2021

Within the margins, and breaking free: Syrian cinema

23 January 2021

Muhammad stayed there until the end of 2012, afterwards moving to Lebanon. In 2014 he moved to Belgium, where he still lives today.

“There are, of course, [Circassian] supporters of the Syrian regime,” Muhammad says. “This stance has emerged since the beginning of the siege of East Ghouta and what happened in Marj al-Sultan in 2012.” Regime forces heavily bombarded Marj al-Sultan late that year, forcing its residents to flee their homes. “There are still elderly Circassians who prefer Bashar al-Assad to others. They consider themselves ‘guests’ in Syria who shouldn’t be involved in current events there, in light of the regime allowing them to organize, learn their own language and practice their customs.”

Muhammad has faced harassment from some relatives on the Circassian side of his family due to his pro-opposition stance, he says. “Suddenly I am no longer a Circassian in their eyes. They started telling me that I’m an Alawite and not a ‘bzamou,’ which means ‘Circassian’ or someone who speaks the Circassian language. When I fled to Marj al-Sultan, some of them refused to interact with me so that others wouldn’t think they were affiliated with me. Some of them told me that because I’m pro-opposition I’d meet a disastrous end.”

Still, Muhamamd says he feels that political stances in Syria aren’t necessarily tied to one’s belonging in a particular ethnic group. He pointed to a number of Circassian elites and figures who remain divided along cultural and intellectual lines.

“Some of them don’t refer to themselves only as Circassians,” Muhammad adds. “And on the other and, there is a long list of Circassian regime officers and shabihah—most notably the former mukhabarat officer Walid Abaza, who held several positions, including secretary of the Baath Party branch in Quneitra governorate.”

As Syria’s revolution transformed from a peaceful movement to an armed uprising, a segment of Circassians became involved in the fighting, especially those from Quneitra and the countryside surrounding Damascus.

A number of armed factions coalesced, including the Ahrar al-Sharkas group, which was affiliated with the FSA and participated in taking the village of Bir Ajam from regime control in late 2012. Some Circassian military leaders also emerged, including Abu Asaad al-Sharkasi, who commanded the Abi Bakr al-Sadiq group. “Sharkas” is the Arabic word for Circassian.

Salah* is a Circassian from Qudsaya who worked there as a media activist. During the revolution, he fled to Homs, where he med Abu Asaad in late 2011. “Unfortunately, many of us Circassians don’t know about people like Abu Asaad,” Salah says. “But we do know about the war crimes of Walid Abaza and his son. In my opinion, Abu Asaad was trying to say that the Circassians had become Syrian, that Syria belonged to them just like anybody else.”

Songs of nostalgia in New York City’s long-lost ‘Little Syria’

05 March 2021

In search of the best picture in the world

22 January 2021

Refuge in Turkey

When battles intensified in the early years of the war in majority-Circassian areas of Damascus and Quneitra, Circassian organizations in Turkey intervened. According to sources with knowledge of the matter, a group in Istanbul and another in Adana helped Circassian families find safe passage to Turkey via Lebanon.

Ali, the former detainee, was among those who were transported to Turkey in 2013. He settled in the Nizip Refugee Camp east of Gaziantep, in southern Turkey. Camp administration had set aside a portion of the camp for around 200 Circassian families. That area came to be known as the “Circassian neighborhood.”

“There was a well-known Circassian person in the camp who would announce flights to Gaziantep from the Rafic Hariri Airport in Beirut,” Ali says. “This was about 20 days after my release from detention. The flights were for Circassians only, and seats were limited.”

SyriaUntold was unable to speak with the Circassian organizations in Turkey, as sources were reluctant to give contact information, though more than one source spoke about the groups and their evacuation efforts.

Among them was Rihab, a 65-year-old woman who left her hometown of al-Qahtaniyah in the Golan in 2013. She had another home in Qudsaya, just outside Damascus. “Someone in Lebanon reached out to us and said that he represented a Circassian organization in Turkey, that he could secure safe passage for us.”

Rihab ended up in a caravan in Nizip Camp. “It was very difficult at first. The caravan was very small and didn’t have enough space for my family of four,” she remembers. “But I felt safe. There were no bombs, no death like there was in Syria. Gradually we got used to things, especially since there were many other Circassians in the camp of all age groups.”

“We used to enjoy the sound of Circassian music that was played in the camp,” Rihab says. “Every evening, we’d gather together. That was until the border between Turkey and Europe was opened. Families started emigrating and the camp emptied out.”

“The camp had residents from all the Circassian tribes, around 200 families,” Celal Demir, former director of Nizip Camp, tells SyriaUntold. “When the camp was dismantled, some of them went to Europe, while others settled down elsewhere in Turkey. Some stayed in Nizip.”

‘When the war ends’

Years of war and instability are pushing more people like Rihab, Rima and Ali to leave Syria with no hope of returning home soon.

Rima, who lives in Ankara with her family, now has a Turkish temporary protection card. She has found a job and says she goes on with her life in Turkey without thinking as often as she used to about her old home.

As for Rihab, who owned a second home in Qudsaya, she says that another family took over the house. A regime security office also opened up nearby. “I tried many times to recover the house. But unfortunately, my attempts won’t amount to anything unless I go there in person. I spoke with the current occupant and he promised me that if I returned to Syria, he’d leave the house,” Rihab says.

Ali, living in Turkey, still thinks about the division wrought on Circassians by the war. “I and many other young people no longer talk with one another because we’re divided along opposition-vs-loyalist lines,” he says. “But these divisions aren’t limited to friend groups. Even siblings are divided. But that’s just for now.”

“The impacts of division will wear off when the war ends. Perhaps we will return.”

*SyriaUntold changed the names of some sources quoted in this report to protect their safety.