Husseiba Abdelrahman is a name that often needs little introduction in certain Syrian circles. There is a degree of respect that follows her among those who know her and are familiar with her history. A novelist and leftist political activist, she spent the better part of eight years in prison for her work.

Later, after 2011, she decided to remain in her home neighborhood in Damascus despite the growing dangers of the war, and despite belonging to a minority group whose members had largely left the area by then. “So that it wouldn’t be said that the people of Kafr Sousseh had expelled the neighborhood’s minorities, I insisted on staying alone without electricity, and sometimes without water, with my remaining neighbors,” she tells SyriaUntold. Husseiba remains in Syria to this day.

We speak with Husseiba about her early childhood influences, how surviving prison influenced her work as a writer, and what she sees for the future of the Syrian resistance movement.

What are the moments that come to mind when you organize your life into certain memories or turning points?

When I read this question, I began trying to fill the gaps of a woman in a state of wandering, a memory bound by the emptiness of time and places lost. Here is what I was able to capture from the defining moments of my 60 years.

The first crossroads moment: When I bade farewell to the [Baath Party’s] Revolutionary Youth Union and the General Union of Syrian Women, in which I had been active during middle school and the beginning of secondary school. I was the most active girl in these groups, and I had powers beyond someone of my age at the time. I left with no regrets, because of the injustice that I sensed.

The second moment: When I came to know some people from the League of Communist Action. I was in a public secondary school at the time, and the shadow of politics began to hover around me. Fantasies about resistance seemed to glow, and the novels I was reading at the time transformed into a sort of raw film.

Hala Abdullah: 'I believe in cinema as a means of resistance’

11 June 2021

Syria’s Labor Communist Party, a rich political history

16 October 2020

As for the third moment, it was one of shock, when I was arrested for the first time on the Lebanese-Syrian border with my bag full of literature, letters and passports for the party. I was a correspondent between the Damascus and Beirut headquarters. I also remember my joy on the day that we and all the other party detainees (except for the officers) were released collectively. They took us on buses and we sang Sheikh Imam [an Egyptian musician] songs as if we were on a field trip. That was in 1980.

The other painful moment was the day my true identity was revealed (I was working undercover) during my second arrest. After 21 days of investigation, during which I rehearsed stories about my fake personality and identity, I was at the doors of freedom. There were no charges against me except for the stupidity that had led me into that house where I had been arrested (according to the investigators, that is). But coincidence, fate and caution led the investigators to bring me into the dormitory to see if one of the detainees knew me. The worst scenario happened, and one of them did indeed know me and shouted my name (accidentally, of course): “Husseiba Abdelrahman?!” Then I was interrogated all over again and I entered the actual spiral of torture that time.

The fifth moment was when I received an invitation to the Heinrich Böll Foundation and I visited Europe in 2001 or 2002 after 25 travel bans, which had prevented me from attending the Golden Jubilee of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in 1998, which I had been invited to.

The cruelest moment was my loving father’s death in 1989, while I was in prison. Another harsh memory was when I was arrested for the third time (on charges of having met with a delegation from Amnesty International) in Damascus in 1993. I remained in prison for eight months without any visits after my father’s death, as my mother was unable to secure visits for me. About a month and a half before that, I was arrested in the home of the late Salama Kila and remained in detention for several days. I lost my personal security as a result of all these summons and detentions. When I published my novel The Cocoon, I was interrogated for months, until Hafez al-Assad died.

In a time as bleak and savage as this, I ask myself why I decided to stay in Syria. Stubbornness? Love? Fear of missing home? Or is it some moral duty?

How do you spend your days?

I start with the miserable present and its impact on the details of my daily life, beginning with coffee as bitter as these days, to reading classical literature to escape the ugliness of violence, the brazen hunting of human souls—whether by bullets, warplanes, misery or fear. There are many causes but only one death.

I also watch black-and-white films that are free of violence. This is another escape from the bitter present, its nets cast down on the spiral of depression. It unfurls itself onto the soul, and it is difficult for us to climb free of it.

At the same time, I meet with friends from different generations, young university students, and friends from years past (remnants of the Cold War). There are also the new friends, whom I met after 2011.

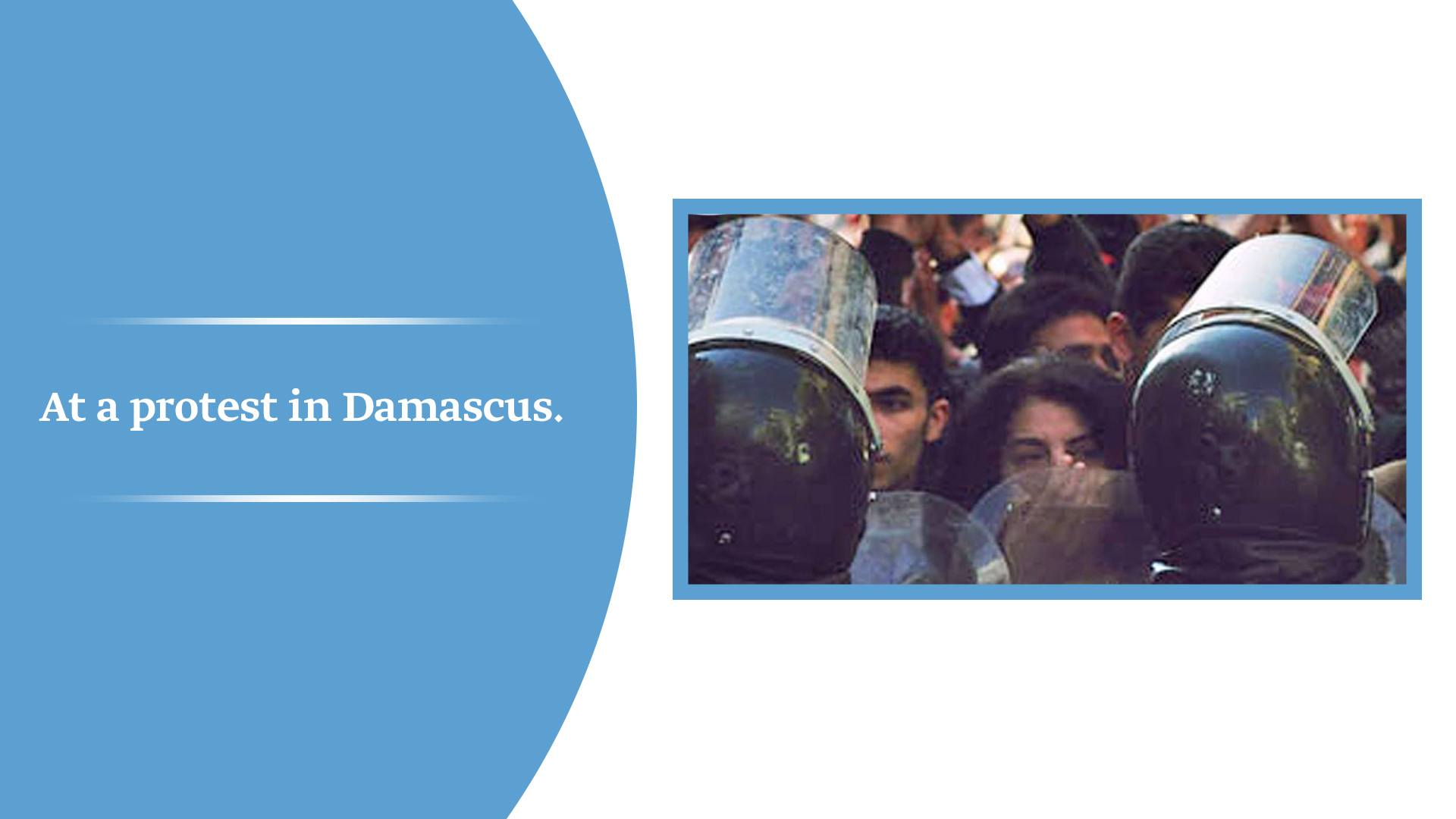

I also take part in some social and political activities, and I follow the ways of my Arab house, especially my room and the surrounding land. At the beginning of the movement, in 2011 and 2012, I persisted in writing in my diaries; perhaps I would publish them someday. This was somewhat of a bearing of my soul.

What made you decide to stay home in Syria after all these years?

In a time as bleak and savage as this, I ask myself why I decided to stay in Syria. Stubbornness? Love? Fear of missing home? Or is it some moral duty? Is it all of these things? Or because, before everything, this is my country, my cruel country, destroyed, scattered, impoverished country, both the killer and the killed, the oppressed and the oppressor, slaughtered by bloodlust? It is my home, it is Kafr Sousseh, its lush orchards overrun with apricot trees, mulberries and pomegranates like the old days. It is the simplicity of its people, the embrace of my childhood and youth, the neighborhood that I never left until I was hidden and arrested.

Damascus’ forgotten ‘Saturday of blood’

07 September 2021

Randa Baath: 'Any cultural act is vital'

12 March 2021

I am both inhabited by it and inhabit it myself. It is the companion of my days, of my dreams and joys and disappointments. It is the neighborhood that sliced me in two (does being a Gemini have any part in halving me between where I live and love, and the place where I was born?). Half of me left with my uncle’s household, my uncle with whom I lived since early childhood. They faced heavy security harassment because of me, even though they supported the regime.

A year after the uprising, and as it began transforming into something more violent and sectarian, my 80-year-old uncle and his wife faced threats. They left their home of 50 years in Kafr Sousseh. My other half remained in their abandoned house among the echoes of its former residents.

I lived difficult days in that empty house. Half of the neighbors had already left. So that it wouldn’t be said that the people of Kafr Sousseh had expelled the neighborhood’s minorities, I insisted on staying alone without electricity, and sometimes without water, with my remaining neighbors. They tried to help me to the best of their abilities because I was alone! There wasn’t a single night I stayed outside the house, amid the fear and the stray shells that showered on us daily. They fell on us when we went out to mourn the martyrs, civilians killed by the bullets. This was between 2011 and 2013, the same stage during which almost all the minorities left the neighborhood.

Very little is publicly known about your childhood. Can you talk about this part of your life? Where were you born, and what was your family like? What were your dreams?

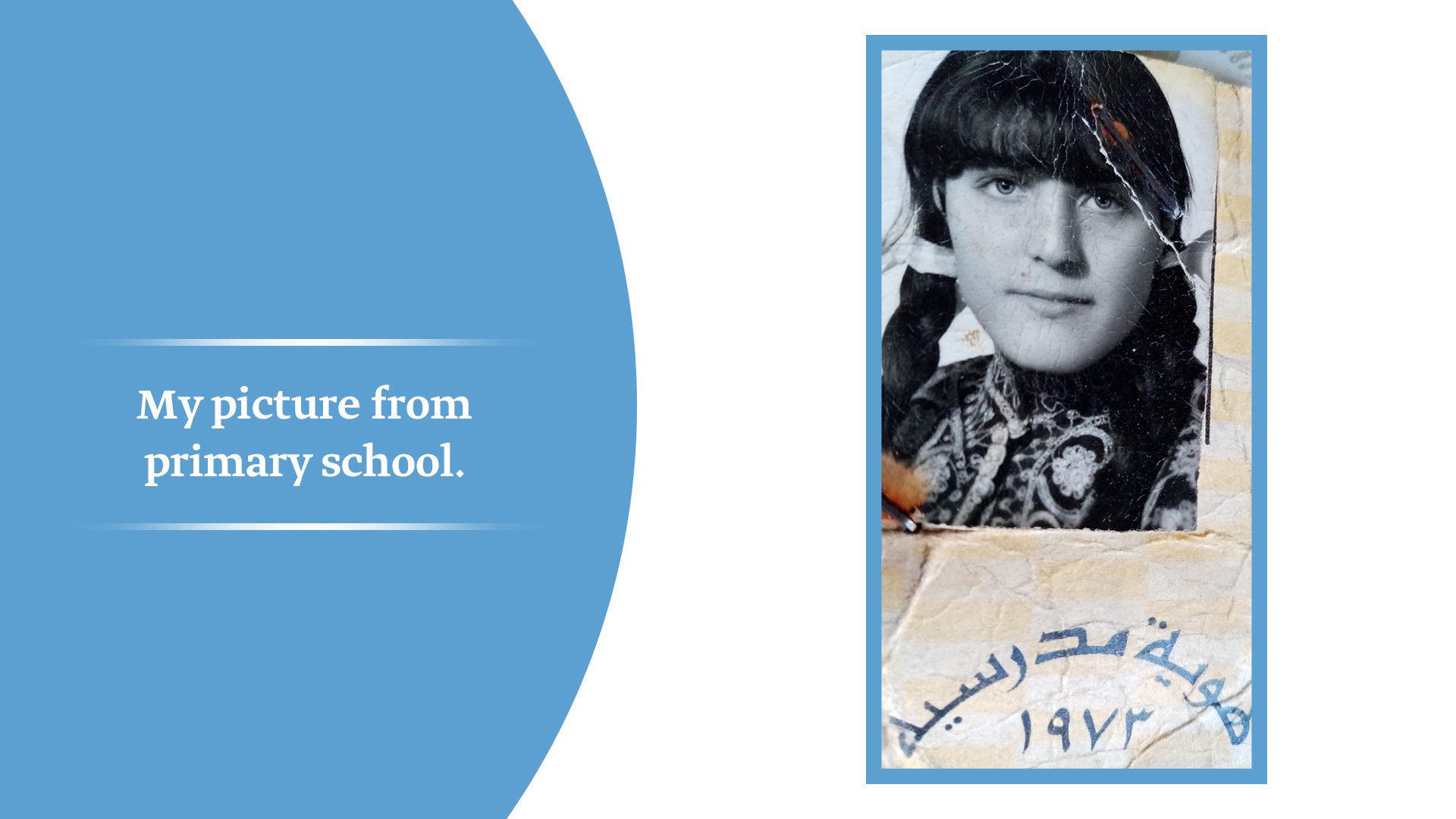

I was a poor yet spoiled child, raised almost alone in a religious but loving household. That girl, with her braids and white ribbons—on the walls of her room she wrote the name of someone who had once lived in it. That person was executed on the morning of the 1963 coup, and the room became her own personal residence, to toss upon her the weight of death. It was a weight that would accompany her until her own imprisonment, and on the night of her arrest. The face of the man who had executed her childhood dreams had left with the picture of the dictator. Those pictures left their marks on me, like that baby bird that I left out for its mother. It was later eaten by the cat (I still have certain feelings about cats to this day).

That calm, spoiled little girl; spots of blue came to stain her skin. She lost her sense of taste. Her fingers fractured, and her body was covered in bruises.

Like any child, I thought someday I’d be a teacher. But my love soon turned to the cinema (I wished to be an actress and director!) and reading. I used to borrow classic books from the school or the library nearby, or buy them with the money that I had saved. I built a collection of world literature classics and books on socialism. The security men seized them along with my picture, which they dispersed to their branches and to bookstores alongside my father’s cherished Quran. He died never having learned why they took his Quran. So I became a woman with a memory severed by absence. I cut my long hair, which turned grey early. My mother used to tell me the grey hair came from the fear, the repeated arrests and severe torture. I spent about eight intermittent years in prison, and four on the edge of danger and arrest when I was in hiding.

‘Recreating a beautiful thing’

27 August 2021

That calm, spoiled little girl; spots of blue came to stain her skin. She lost her sense of taste. Her fingers fractured, and her body was covered in bruises, emitting screams and lifting the dust around her. And then my mother and father both died wondering why I had gone to prison. I had so many opportunities before me. I could have been an influential bureaucrat or gone to study cinema, which I truly loved. But instead, I had “radical sentiments.” I couldn’t accept staying in one place. It didn’t occur to me or to my family that I might someday hate oppression, and that my soul would search for justice.

So I left the Baath Party early, and I joined the communist opposition in search of justice and an end to oppression. Literature played a big role in this shift. It took me, and still takes me, to fantasies, places and shadows. It was joyful at times and sorrowful at others, alternating between rich and poor. It still influences me, albeit to a more limited extent, even now.

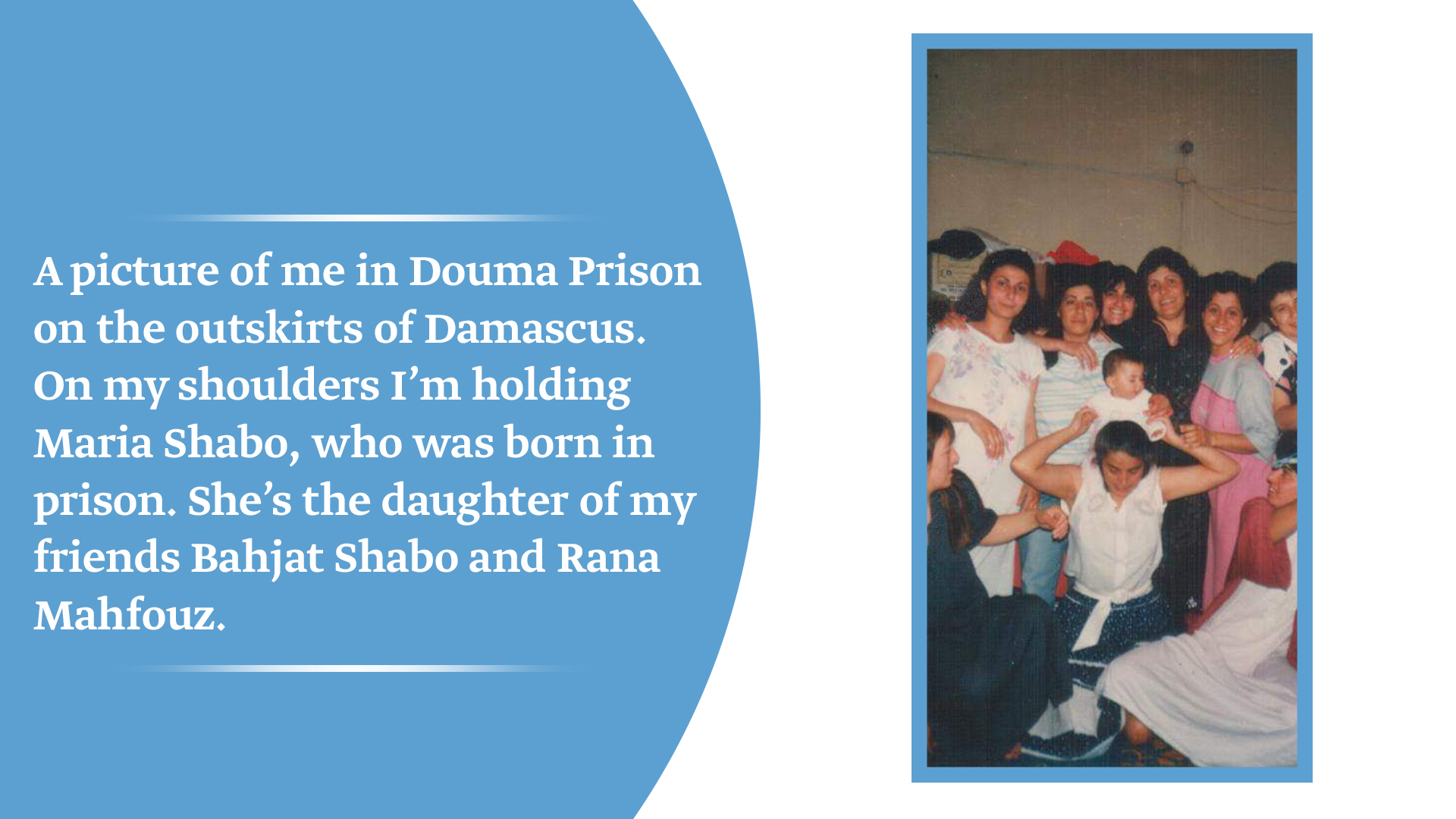

That’s why the first thing I did when I got out of prison the third time was to gather my papers (which I had written during imprisonment). I reformulated them and published them in my novel The Cocoon as a way to ease the burdens of prison. The novel discusses a women’s prison. I also published a short story collection, He Fell by Mistake, on the same topic.

Then I pulled together stories from my family and their visitors that I remembered from my childhood. I interwove them with my imaginations of their fear, movement, faith and rituals in my novel Manifestations of My Grandfather, the Migrant Sheikh. The novel became an early cry about what fear, isolation, ignorance and religious ideology might do before the “big bang” that drove us to murder, and to a country that is both alive and dead, displaced and grieving. A country of the dead. The country, its rivers and its mountains all constrained them until they became numbers with no meaning or value. Labels are subject to labels.

Now we are living in a swamp of both present and deferred death, a destroyed country divided inside and out. Our hands and our feet are in shackles. Or rather, our necks are tied by a yoke, amid lost labyrinths of time that pull us back to a primitive daily life. We use firewood for fuel and heating, and for oil lamps (a sort of brutish romanticism). This is after all the change that we dared to dream of in the 2011 uprising. I call it an uprising and not a revolution because a revolution means a vision, a program and revolutionary tools, which weren’t present during what became known as the Arab Spring.

How do you see all that has happened this past decade in Syria, and how things are going today?

Unfortunately, I was not optimistic during the Syrian uprising despite having participated in it myself at first. I observed the structure of the regime and its position on the movement, which it saw as an Islamist uprising, which meant (from their point of view) the expulsion and killing of minorities. That is why the poor and minorities (to a lesser degree) from the regime’s environs did not stand with the uprising—and here I mean regular people, not intellectual elites.

This is what gave a religious and sectarian character to the movement and facilitated sectarian incitement, whether in the regime’s circles or in the opposition movement, which in turn facilitated the interference of Western and regional agendas. The uprising was flooded with money, weapons and sectarian fervor.

I saw from the beginning that we were headed towards a bloody struggle, but the state we are in today is one of surrealism. Everything is destroyed: stones, humans, values, morals, principles. All are sold in the slave market, the market of looted goods. The regime bears the primary responsibility for its use of oppression and violence of all forms and levels. The other factions bear another portion of responsibility, if to a lesser degree, since they opened their pockets and homes to foreign agendas.

We will never climb out of this quagmire without a political solution that picks up the pieces of us and of our country. This requires an international and regional consensus because Syrians—whether those with the regime or the opposition—have left behind the game and political action. The solution has fallen into the hands of external powers, unfortunately.