Before the internet came to Syria, there were cassette tapes—thousands and thousands and thousands of them, spread out across three decades of taxi stereos and music shop shelves.

Syria’s “cassette era” bookends a period of massive change in the country’s music ecosystem: from traditional folk tunes measured out by wood-framed drums to the arrival of synthesizers and buzzy electronic beats; from the pre-internet days of locally produced plastic cassettes for sale at bus stops and kiosks, to the downloadable mp3s that would, eventually, make the tapes obsolete.

Yet the era, which lasted from the late 1970s to about 2010, has long been underappreciated, according to musician-producers Mark Gergis and Yamen Makdad. The two men co-curate the Syrian Cassette Archives, an online library of the hundreds of cassettes Gergis collected on multiple trips to Syria from 1997 to 2010. Though in the works for a couple years, the Archives launched its online listening platform in February. So far, dozens of cassettes are featured on the platform, including live-recorded wedding celebrations, “shaabi” electronic love songs, Hourani folk tunes and Kurdish- and Assyrian-language music. They also plan to release a series of oral history interviews with the artists involved in Syria’s cassette tape era.

Gergis’ and Makdad’s efforts could be saving much of the era’s music—oftentimes hyper-local or popular tunes that previous music enthusiasts dismissed as unimportant—from being lost to time.

“These ephemeral tapes; this is exactly what we hope isn’t lost,” says Gergis. “Perhaps somebody, Syrian or otherwise, can find something here. They might find something that they never heard as a result, because we happened to pluck that tape out of history, out of a window of time, and preserve it.”

Songs of nostalgia in New York City’s long-lost ‘Little Syria’

05 March 2021

‘Recreating a beautiful thing’

27 August 2021

SyriaUntold spoke with Gergis and Makdad earlier this month about the project, their own musical backgrounds, and about the importance of preserving Syria’s “shaabi,” or popular, everyday, music. Why is it vital to document what otherwise might be overlooked?

This conversation has been edited for flow.

Mark, can you start out with how you became interested in Syrian cassette tapes? What is your musical background?

Mark: Growing up in the States as an Iraqi American, I was exposed to a lot of Arabic music through my extended family in Detroit and through my father playing the classics, from Iraqi classic records to Umm Kulthoum and Fairouz. We would go to Iraqi weddings when I was very young in the 1970s and 1980s, and there were small orchestras, sometimes with the flute and kamancheh and percussion. Eventually, in the 1980s and 1990s, they’d be playing choubi music. It was always interesting to me.

But the American assimilation machine is strong. My father wasn’t exempt. He sort of ditched all of his cultural “stuff” because it became very difficult politically, with the Iran hostage crisis and the war in Lebanon reaching its apex in 1982, and then eventually we had the Gulf War and then 9/11 and just blow after blow. Being Arab American wasn’t something that a lot of people wanted to announce. It became a negative thing.

At the same time, you saw a lot of demonization of the Middle East in the media. Always negative. I guess around the First Gulf War in 1991, I got super politicized and jumped back into Arabic music. I tried learning about this music in a pre-internet world where we had diaspora shops like Iraqi shops in San Diego and Detroit and some Egyptian and Yemeni shops up in the [San Francisco] Bay Area. I’d be purchasing tapes and eventually CDs, and records too. There was an Arabic record store in San Francisco that had been around since the 1960s.

My family is Assyrian—we’re Chaldean Assyrian—so we also had a special focus on Assyrian and Chaldean music, which there was plenty of in the States. I learned about these Assyrian villages and the Khabour River in eastern Syria, and got the idea to visit. I had never traveled outside of North America. So Syria was one of the first places I went in 1997, with music as a kind of driving force behind everything I did. I thought I could go there, listen to the local radio, learn about the music and buy as many cassettes as possible. It was dizzying. I fell in love with the place immediately, everything about it. The cassette kiosks and shops had thousands and thousands and thousands of cassettes, so I just bought as liberally as I could, as much as I could fit in my suitcase.

Yamen, can you talk about your background with music? What music did you grow up with? How did that interest develop into the work that you do know with the Syrian Cassette Archives?

Yamen: I was born in Damascus in 1990 and caught the last bit of the cassette era in Syria. From there, the cassette stores turned into CD stores. Mainly I got my hand on whatever was from the cassette and CD shops and from my sister’s and father’s collections. But I did start listening to some Syrian alternative music like Kulna Sawa and Anas & Friends. My father would listen to tarab music, folk music from all over the region. That stuck with me. Folk music from Lebanon, from Egypt, from Yemen, Sudan and Syria. Also, the cassette stores would range from the Backstreet Boys, Nawal El Zoghbi and stuff like this.

Every wedding celebration, every party was recorded and distributed. For a lot of these, you’d find the cassette one year, and then next year when you went back to Syria it would have disappeared.

But then the internet came and I would just download and archive in my own way, and I would burn a lot of CDs for my friends. That led me to start DJing in Syria. When I moved to London, I continued DJing and I was part of a couple of DJ collectives. Then we started this radio show to basically just hang out in the studio and talk about music. So I reached out to Mark, who was about to move to London. That was when Mark was starting to think about bringing his cassette collection from the US and digitizing it.

Can you recall an early or defining moment in which you realized the archival or cultural importance of Syrian cassette tapes?

Mark: My last trip to Syria was in 2010. And I just watched the decline, hearing the stories from friends and contacts in Syria, terrible stories. Eventually, there was ISIS; it was beyond anything that I thought was possible. For me this was hard to process, even just as an outsider.

Around 2017 I started thinking about some of the nature of the cassettes and how ephemeral they are. I started thinking about the effects of war on culture in general. I had researched and worked a lot with Cambodian music, which had faced complete destruction and annihilation. There were even dance forms and age-old musical forms that had been lost, as in any place that’s been touched by war and dispersion and forced relocation. I started thinking about the effects that would have on music and how a lot of these cassettes were ephemeral—especially the shaabi and dabke cassettes.

From Ottoman Syria to Argentina

02 August 2021

What do you mean when you say that they are so ephemeral?

Mark: You have the classics like Umm Kulthoum or Farid al-Atrash, which last forever. They’re on every shelf and they appear on CDs, mp3s, flash drives, YouTube. They are well documented, even on phonograph records.

As for the nature of cassettes—there were so many thousands of them in Syria. In fact, they were one of the biggest producers and exporters of cassettes in the region. The cassette era was also one of the longest musical eras, from the late 1970s to 2010-ish.

The lifespan of these cassettes was short, especially wedding tapes. And the music existed solely on cassette. It was never on phonograph record or digitized for CD. It was just seen as a workaday way to get the name of the singer out there. You’ve probably heard, and it’s true, that Omar Souleyman has 500 cassettes to his name. Every wedding celebration, every party [he performed at] was recorded and distributed. For a lot of these, you’d find the cassette one year, and then next year when you went back to Syria it would have disappeared.

I started thinking about the high turnover rate of those cassettes, about the cultural amnesia that can happen from war and the demographic shifts happening in Syria, where music may never sound the same from region to region.

Yamen: With the Syrian cassettes generally, and especially with the folk cassettes, I had this interest throughout my career—to collect music, to share it and bring it to life. But with the Syrian cassettes specifically, I think I started realizing the risk when the war started. I was constantly asking my dad what he still had from his collection. On the first trip I made back to Syria, I tried my best to look for my records, vinyls, cassettes.

I also do research on the singers featured in the Syrian Cassette Archives, and I’ve realized the specificities of this industry. The Syrian cassette industry was very different from any other music industry in the region in the sense that it was huge, yet very un-institutionalized. It was very grassroots. People would record music in their own communities and it wouldn’t reach over into the main cities.

That aspect of large, local grassroots music production in Syria—was it specific for the cassette format?

Yamen: Yes, and of course some of the cassettes would make it to the cities. But generally, I think for each region the majority of the production would live and die in that area. There wasn’t enough interest in the cities, there wasn’t a market. Some of the different regional genres, like Hourani music, the Jazireh music [from northeastern Syria] or music from the coast didn’t achieve the kind of public reception seen for artists like Sabah Fakhri and others who performed on TV. But generally, the majority of Syrian musicians started recording through cassettes and those cassettes just stayed in their own communities. We started realizing the importance of sharing these cassettes and celebrating them. It’s super important for the continuity of Syria, the country and its people.

Mark: This is a contemporary musical history that we’re focusing on, this cassette era. But it’s quickly becoming historical, and because of recent events, is moving into the past. It’s a window into a very specific sliver of time in a Syria that has changed so much. In that sense, it’s very important for us to talk to the people who were involved in it, those who are still with us. Sometimes we’re talking to next of kin at this point.

There’s also never really been a spotlight shown on that era. It’s been seen as kind of a workaday era, in the sense that some of the people we’re interviewing have never been interviewed before. Some of them are surprised about the curiosity and our level of depth in wanting to know how it worked.

We started realizing the importance of sharing these cassettes and celebrating them. It’s super important for the continuity of Syria, the country and its people.

The online archive includes a number of cassettes of “shaabi” music, or production that some people might call “low culture.” Mark you said in a previous interview that this type of music had a poor reputation among Syrian “intellectuals” or urbanites. Can you talk more about the classist undertones that were going on here? What is it about this type of music that these urbanites were criticizing?

Mark: As an outsider looking in, I wasn’t as aware of the gravity or intensity of these stigmas. I know in my own family, when you’d put on choubi music, they’d talk about it like: “yeah this is nice, but the real music is such-and-such.” There are levels of what you can and should appreciate.

People were begging me not to focus on this kind of [popular, or shaabi] music because in their opinion it wasn’t Syrian. There were brilliant minds and brilliant artists and craftspeople, engineers and architects in Damascus who saw me elevating someone like Omar Souleyman, and it was quite a confusing thing for them to process. I can understand this completely, putting myself in their shoes.

Yamen: I think there are two levels to it. There’s the longstanding city-centric approach in Aleppo and Damascus. Of course, they have been the biggest social, cultural and economic hubs of Syria for thousands of years. So they always had the cultural weight.

When the Baath Party came to power the focus was on building the nation-state of Syria. The state held a cultural monopoly. State-run TV channels and radio stations ended up playing the same things that were being played in Iraq, Yemen and in Egypt, focusing on this pan-Arab cultural approach. This stemmed out of the first Congress of Arabic Music in Cairo in 1932, which essentially decided on what “Arabic music” is.

Sultana’s story

10 July 2021

What was “Arab music” to them?

Yamen: Before the formation of orchestras in Syria, the focus was on Arabic classical music. This is basically the music of Mohammed Abdel Wahab, Umm Kulthoum, Farid al-Atrash, Asmahan. These were the first stars of Arabic classical music, as decided by the congress in 1932—this was Arab music, this was how you notated it, and this was the correct style. And that created an academic narrative: “This is music, and this is not.” They decided which music was worth following, music that people should create.

Why do you think the people who championed this kind of classical music would have criticized more local or shaabi forms of Syrian music? I was listening to one of the cassettes of Hourani folk songs from Suweida, and it was just incredible music—what was the criticism of this kind of work, and where was this criticism coming from?

Yamen: We need to be clear that people from the south, they celebrate this music. To them, this is quality music and they understand its history. It comes from their folklore, their traditions, their celebrations, their harvest season. They understand it, they vibe to it, they listen to it. And the same goes for music from other parts of the country. On the coast, they celebrate their music, and the same goes for the northeast.

But the cities, there is this [perception] that Damascus and Aleppo are the best places and everything outside is backward. And that applies also to music. Having said that, people in other parts of Syria celebrate their local culture as well as the mainstream culture. It’s common that people in Damascus and Aleppo would look down on such music.

However, there is a distinction between shaabi music and what is considered “folk” music. Within this narrative, it is acceptable for you to perform folk as it sounded historically. There’s this type of traditional harvest song in the south of Syria—this is acceptable, meaning that it must stay as it was in the past, in performances on stages for festivals. That is considered okay.

But what they have an issue with is what’s referred to as shaabi music, which is the continuation of that folk music. They want to keep that music how it was in the 1930s or 40s. They don’t accept it evolving with technology, with migration. The sound that evolved from that folk music is what they look down on the most.

For various reasons, I’ve been thinking a lot lately about that idea of “low culture” or “tackiness,” and the kind of classist implications behind criticizing something as tacky or low, as if it matters less, or isn’t real artistic production worth preserving or studying. Why is it important to preserve this kind of music, this shaabi production, alongside more classical forms?

Mark: We can find these kinds of musical prejudices in any culture. If you listen to classical music in the West, you have to embody the lifestyle that comes with it, with the fine wines and those things.

We’re situating this phenomenon of “coolness” or what’s right or classy or nice within the Syrian context, but of course it exists everywhere, and we’re all part of it on some level.

I have always strived for an open-ended, eclectic approach to music. I can find beauty in any music, from a TV ad that might be really cheesy, to an NSYNC song, or a Justin Bieber song to the most underground, crazy art-rock stuff.

I can appreciate and love Farid al-Atrash, but I can also love this so-called “lowest” form of shaabi music. In that shaabi music, you hear incredible instrumentation and people who live and breathe and eat this music and who have studied it. There is serious unnoted methodology going on here and application of skill and expertise that’s centuries-old in some cases, or they’ve hybridized it with synthesizers, yet still draw from this rich past. I find that so exciting.

Yamen: I agree. We’re situating this phenomenon of “coolness” or what’s right or classy or nice within the Syrian context, but of course it exists everywhere, and we’re all part of it on some level.

Mark: As much as we respect the academics and the institutions that have brought music to our attention since the early days of recorded music, an elitist approach permeates academia and institutions. And it isn’t checking itself for the exclusivity that it promotes. In my opinion, it’s quite destructive. That is the very reason that we weren’t hearing certain sounds earlier, back in the pre-internet days. Those sounds weren’t made available because there was a group of people deciding that it wasn’t important enough. If we only focus on what is state-sanctioned or institutionally proper, then that’s destructive to our holistic understanding of a place.

Within the margins, and breaking free: Syrian cinema

23 January 2021

On the website, you write that the stories of most of the artists featured in the Cassette Archives have “rarely been told.” Is there a particular artist from the archive whose story has stuck with you, or that people need to hear about?

Yamen: While talking to those artists, a lot of them are very positively surprised. Some of them actually got scared, and some of them really appreciated the project because they felt that nobody had been serious about them before. Because of [misconceptions], they never got any attention from the news outlets we have in Syria.

Some of them have been doing music for 60, 70 years. One artist we spoke with was Saad al-Harbawi, who hasn’t had the right amount of media attention.

Can you talk a bit more about Saad’s story? What genre does he work in?

Yamen: I think he’s from Tal Tamer [in northeastern Syria]. He was born in the 1930s, and he plays the rababa and sings at weddings. He still does this. His father was a Bedouin poet. When we were interviewing him, he started performing for us. He sings in Kurdish and Armenian because his area of Syria is very diverse. So he just plays the rababa while he starts singing Kurdish music, and other languages. It’s crazy. He’s also one of the longstanding wedding performers from the pre-electrification era and then kept playing after electrification. He spanned both eras. Before electrification, he used to just walk around the party playing music so that he could be heard.

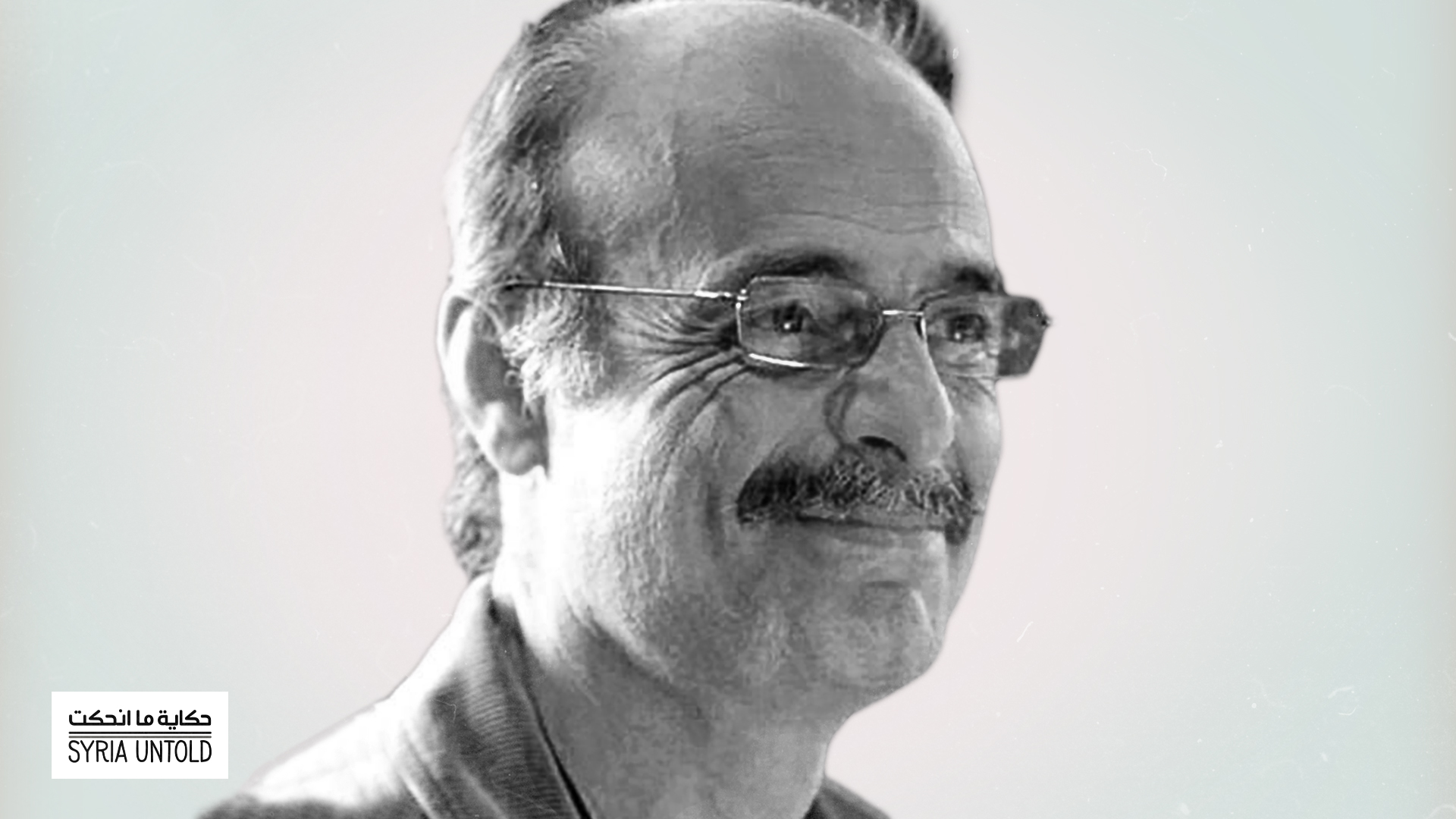

But my favorite artist we interviewed was Ahmad Qassim. He’s just a wealth of information and experiences and has an interesting approach to life and art. He’s a Hourani singer and also a kind of ethnomusicologist—he’d go out and document Hourani musicians when he used to live there.

He still lives in southern Syria and performs there?

Yamen: No, he’s in Jordan now.

Mark: It’s not been easy to find some of these artists and production companies. A lot of them were displaced, and many are spread throughout the world right now or they’re out of the music business.

But it’s been interesting, with Ahmad Qassim, for instance, talking to him about the cassette period, because he started singing around the time this [electronic] hybridization was coming into full swing, bringing electronic synthesizers, electronic drums.

What decade would that have been in?

Mark: The early synthesizers started coming in via Lebanon, China and Japan in the early 1980s. It is asking quite a lot of people who are used to dancing a certain way at weddings, to organic acoustic percussion, to suddenly give them a regimented electronic beat.

The cassette era documents that time, when more acoustic folk started getting electrified.

I’ve been thinking a lot recently about why I and others keep focusing on arts and culture even as Syria remains in a state of war. Some people might say it isn’t important to focus on these things at a time like this; that there are “bigger” topics to focus our energies on.

Why are arts and culture important nonetheless? What can music and preservation do for us amid violence and, oftentimes, violent cultural erasure?

Mark: We work with what we have. Yamen and I are arts and culture-based people, that’s been our plight, and those are the tools that we work with. Music is a gateway, like food. That may be the most naive, very basic, entry point for someone into finally thinking about the culture that previously was made invisible to them. That’s from a Western point of view, though.

In the US, Syria has always fallen under this category of a “rogue” or “pariah” or “terrorist” state. This idea is constantly reinforced by all forms of media, entertainment, academia and literature. It’s been a mantra for politicians, also. At the same time, nobody knows anything of the vibrant Syrian cultural history, nothing about its extant culture or people.

When I started visiting in the late 1990s, there weren’t many Syrian recordings available in the Western market, so I was able to listen to these cassettes and was convinced that I should begin sharing these in any way possible. I think arts and culture, at their best, can be transformative.

Yamen: It’s a humanistic act to preserve culture. What is a human without who he is, without his history, without music, his food? It’s a necessity. I don’t see it as a privilege. Literally, who are you without the things that make you who you are?

Last, we’ve talked about how this whole cassette ecosystem in Syria is interesting partly because it is so ephemeral, that cassette tapes are these vulnerable documents of beautiful moments in time.

For example, one of the cassette tapes in the Archives was simply a recording from a wedding party in the 1980s in Harasta, outside Damascus. At some points in the tape, the wedding guests even sing along. If not for this rather informal recording, this moment and the music that came with it would have been lost forever. But because we have an archival record of this cassette, we can enjoy the music along with the people who were at the party and experience this moment with them, preserved in time. I find that so lovely—can you talk more about this ephemeral nature of cassette music?

Mark: It is a window into that time and everything that time embodied. These ephemeral tapes; this is exactly what we hope isn’t lost. Perhaps somebody, Syrian or otherwise, can find something here. Maybe they already have vast knowledge, but they might find something that they never heard as a result, because we happened to pluck that tape out of history, out of a window of time, and preserve it. There are so many thousands of tapes that weren’t.

Yamen: The act of recording sounds is a crazy idea. Now we’re used to it, but the act of capturing something and replaying it is a hundred-year-old thing. For me to take these cassette recordings and replay them in a different context here in London, in my flat, is so interesting.

There’s a responsibility when resharing the sound, to contextualize it. When you play these wedding tracks for a crowd in London, people jump off the roof, the music has that much energy. It’s so raw and so real and you feel that it’s thousands of years of accumulation of festivities being unleashed on people. I see the importance of sharing this onwards and onwards and onwards.

Mark: It must be strange for some people, even the creators of this music, to see it elevated. Once you have an archive and you’re sharing this, you’re shining a spotlight on something that, maybe, was never really intended to have a spotlight. It was supposed to fit into a certain context at a certain time.

You can easily be accused by people: “why are you elevating this?” Like the Omar Souleyman argument. But you work with what you have and whatever is available from that period of time, the cassette era. It was daily life. You could have found it at a Syrian bus stop, or at an institutional cassette shop. Once we put it on a pedestal or under glass, there’s a tendency to elevate it into something like: “This is the sound of Syria!”

No—it was just one of many thousands of sounds.