SyriaUntold originally published this piece in Arabic here. Read more of our Arabic-language coverage of Syrian detainees and forcibly disappeared people here.

I can no longer remember when and where I met Khalil Maatouk for the first time. What I do recall that he became a close, dear friend whom I could not stand to be away from for long.

I made a point of meeting up with him every now and then, calling him, asking him how he was doing and about his health. His ability to move was limited due to lung weakness brought on by an advanced case of pulmonary fibrosis.

We would agree to meet in front of the court or the parking lot and move to the destination that suited us, most often Hijaz Cafe, where the outdoor seating with the stretch of sky above allowed the flow and renewal of air; ensuring that the smells of argileh and cigarettes of all kinds and colors would not sit heavy on his tired chest. I would often arrive first and wait, after checking my watch and thinking: “He’s late, might there be a problem?” I would call, asking, “Where are you, man?” “Stuck in traffic,” he would answer. “I am on my way. I’ll be there in a few minutes.”

A forced disappearance in Raqqa, and the empty spaces left behind

09 December 2020

Mending what has been broken

12 February 2021

Minutes flew by and slipped between my fingers and still, this time, no sign of Khalil. It was not the passage of time that worried me, but my fear for him and my longing for his smile and the cheek kisses we always exchanged. He arrived, but he was not alone. A tall, grey-haired man with a subtle smile accompanied him. After a quick kiss came the introduction: Muhammad Zaza, a friend and neighbor who volunteered to drive him from his place to the city center.

“Welcome, brother Muhammad,” I said. “Your efforts are much appreciated.”

Mohammad answered: “Khalil deserves our solidarity because he has stood by all the detainees equally, without discrimination or differentiation, for years.”

Tea, coffee and herbal infusions were served, and he began to talk about various lawsuits against prisoners, jail visits, powers of attorney, release requests and dozens of cases. Time passed, while Muhammad listened but said little. His presence was light, and he did not interfere in conversations he had no knowledge of or connection to.

Khalil then got up, justifying his departure: “I have to attend an interrogation,” “I have a question about a release request,” “I have a power of attorney to arrange.” His tasks were endless. Our meetings stopped. Khalil was arrested—the same Khalil who had endeavored to release thousands of Syrian prisoners. His radiant smile and resonating laughter vanished. For years, I did not see his face or smile, and my cheek missed his kiss.

A risky mission

Khalil was not just another traditional lawyer moving between his office and various courts, from the Supreme State Security Court to the Criminal Court and the Military Court. His tasks were not limited to meeting clients, preparing defenses and pleading cases before the courts.

In addition to his abidance by the law and respect for the methods of fair litigation, Khalil took on cases of political prisoners. He had faith that people could demand their constitutional and legal rights and practice their public and private freedoms. He believed in equality and social justice, and the right to express aspirations for a better political, social and economic system.

Khalil gave 20 years of his professional life to a delicate and risky mission: defending political prisoners in an unconstitutional and illegal environment.

Pushed by his belief in the importance of separating his work in the legal and human rights field from his political stances and ideological backgrounds, Khalil resigned from the Syrian Communist Party. He wanted to free himself of partisan shackles and draw inspiration from his personal beliefs to defend Syrian prisoners of conscience. He engaged in rights frameworks that aimed at exchanging and promoting experience, gathering potential, coordinating work and distributing roles.

Due to Khalil’s experience and efforts, he became president of the Committee for the Defense of Prisoners of Conscience and the Syrian Center for the Defense of Detainees and the director of the Syrian Center for Legal Studies and Research. While Khalil was in prison, the Dutch organization Lawyers for Lawyers shortlisted him for their annual award, in appreciation of his work in defending human rights over the course of two decades.

Khalil gave 20 years of his professional life to a delicate and risky mission: defending political prisoners in an unconstitutional and illegal environment. A state of emergency and martial law has been imposed in Syria since 1963, thus weakening the lawyer’s role and threatening his life. Fayez al-Nouri, presiding judge at the Supreme State Security Court, forbade lawyers from speaking. He once expelled lawyer Razan Zaitouneh from the courtroom because she was translating the proceedings to a German woman sitting next to her. She was banned from re-entering and from pleading the case before the court.

Long night to resurrection

05 February 2021

Khalil volunteered to defend every prisoner, regardless of their political background, be it Islamist, democratic or leftist, or their national identity, be it Arab, Kurdish, Syriac, Circassian, etc. He defended prisoners from all provinces and political and ideological circles, from Kurdish activists in the 2004 intifada to those imprisoned after the 2005 Damascus Declaration and the Beirut-Damascus Declaration in 2006, including Michel Kilo, Mashaal Tammo, Anwar al-Bunni, myself and others.

He also defended individuals outside of known political circles, such as Tal al-Mallouhi, a young woman who was punished by the regime for opinions she had published online. The Syrian judiciary sentenced her to five years in prison based on fabricated charges of espionage for an enemy state, and she was not released even after completing her sentence. Khalil defended young men from Qatna, Otaybah and al-Abadah in rural Damascus and from Hama and Aleppo, who were eager to fight against the US invasion of Iraq in 2003. The regime arrested them to settle scores as part of its rapprochement with the US. Khalil did not only volunteer to defend prisoners, but he also paid the attorney fees many times for prisoners who could not afford them. I personally witnessed this several times before the infamous Supreme State Security Court.

Khalil faced pressure from the intelligence apparatus, which summoned him repeatedly to dissuade him from volunteering to defend prisoners, and issued a travel ban against him from 2005 until 2011.

With the outbreak of the Syrian revolution in 2011, Khalil’s burdens increased. Arrests and abductions were on the rise. He opened his doors to the parents of prisoners and forcibly disappeared, in a direct challenge to the regime and its oppressive institutions. The regime decided to end this phenomenon by arresting him and forcibly disappearing him.

Disappearance

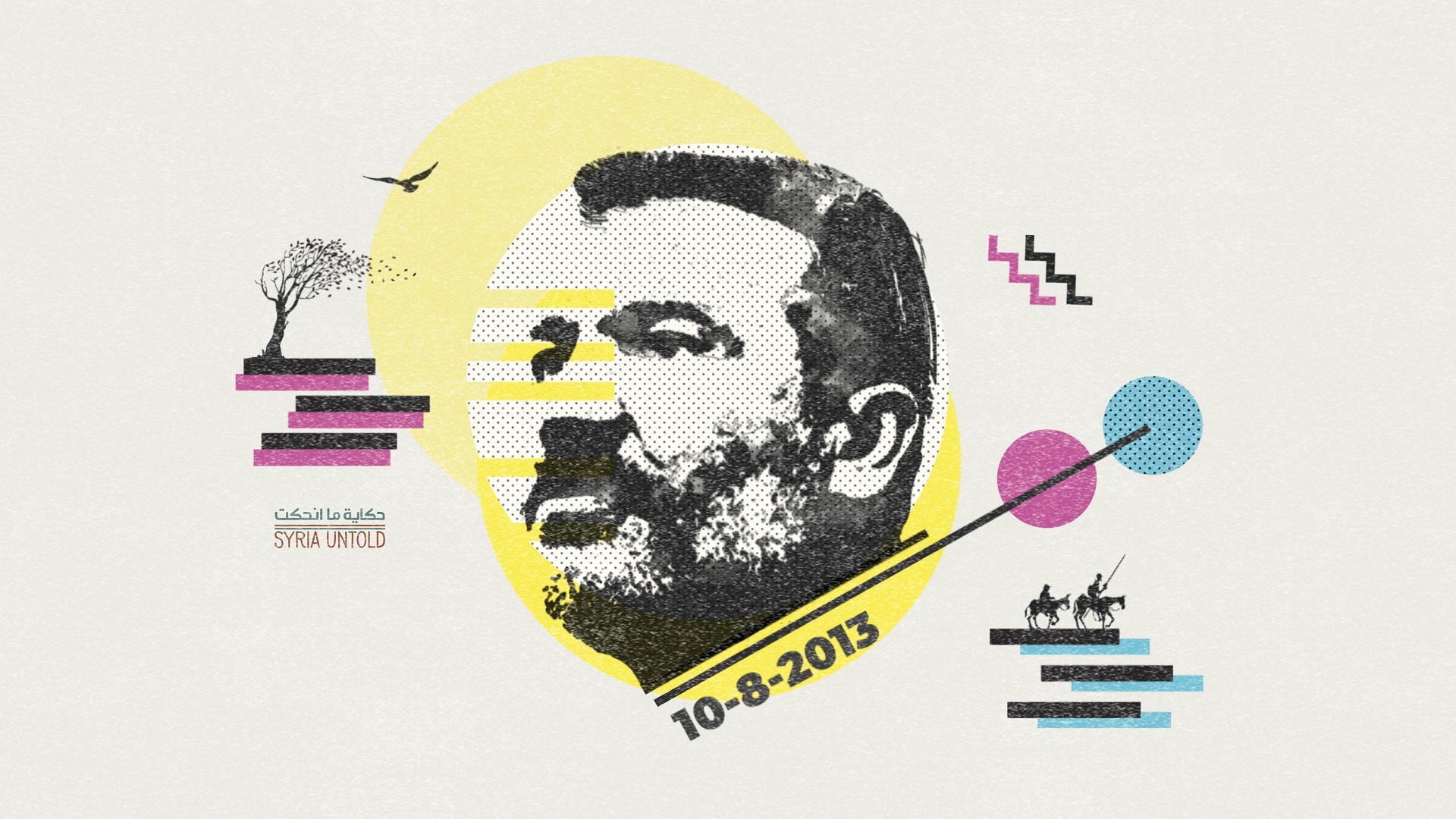

Khalil and his friend and neighbor, Muhammad Zaza, were abducted on the morning of October 2, 2012. Zaza had been driving. The two were headed from Khalil’s house in the Sahnaya suburb of Damascus to his office in the capital.

No news about them was revealed, and the regime’s intelligence denied holding Khalil or having any knowledge of what had happened to him, though he had disappeared on the road connecting Sahnaya to Damascus city, where regime checkpoints abound.

No information about his place of detention or health condition was provided either. His nuclear family—his wife, his son Majd and his daughter Ranim—were prohibited from seeing him, and he did not get the chance to appear before court. It has been over eight years of his family, parents and friends being fed bits and pieces of information about him from prisoners released from the regime’s dungeons and detention centers, in the hope of discovering his whereabouts or anything about his health condition. Former prisoners have asserted that he was present in one of the intelligence branches’ detention facilities.

Khalil’s abduction and his prolonged disappearance mirror the thousands of abductions and disappearances of protesters who flocked to the streets in all Syrian provinces to express their frustration with the tyrannical regime, and to demand their rights to freedom and dignity.

Opposition political leaders, like Abdul Aziz al-Khair, Fayek el-Mir, Raja al-Naser and others, were among those abducted. Khalil’s abduction reminds us of the bitter struggle he and dozens of courageous lawyers underwent in their fight for the freedom of prisoners and their rights to a fair and legal trial.

His disappearance also reminds us of his efforts to expose the violations taking place in courtrooms to the local and international public. These courts overlook proof and evidence, and are controlled remotely by other parties. They pronounce their rulings based on orders from the intelligence apparatus and manipulate international organizations by orchestrating the trials of political opponents and dozens of jihadists in the Supreme State Security Court and Criminal and Military Courts, in the presence of observers from Western embassies. Their goal is to give these observers the impression that the state is being targeted by terrorist groups.

For all the efforts he made to ensure freedom for prisoners, and for all his legal, professional and coordination activity, Khalil Maatouk deserves to be venerated. His cause is worthy of remaining on the opposition’s agenda. Khalil deserves campaigns that remind us of him, and he deserves demands to reveal his fate and release him.