Read this piece in its original Arabic here.

I’ve been living outside Syria since 2014. That’s seven years, two of them in Beirut and the remaining five in Berlin. The strange thing is that throughout this time I haven’t felt for a moment that I’m living “in exile.” It simply wasn’t something that crossed my mind until someone asked me about it one day during a conversation.

But as the questions multiplied, and my stay outside Syria lengthened, the word began to seep into my thoughts. My mind swirled with many questions. Who is really in exile: me in Berlin, or someone trapped within the borders of the “homeland” in Syria without water or electricity, living under fear, lacking even the most basic human rights such as voting, citizenship, travel, access to information, education and health? What even is exile? Home? Is home the country where we are born, learn to speak and then lose everything, or is it the country that provides us with everything (apart from our birthplace), including citizenship and a passport?

If the latter, then what is our relationship to our birthplace? We are no longer tied to it, and yet sometimes our nostalgia for it seems to almost kill us. What remains of the idea of exile amid globalization, and our ability to communicate constantly and directly with all our loved ones anywhere in an instant?

Thoughts on exile in Germany

17 July 2021

From Aleppo to Beirut, cities burning

26 February 2021

My relationship with exile cannot be separated from my relationship with home. Both of them change over time, though remain the inverse of one another. Whenever one of them changes in my mind, the other must also develop and change. The meaning of exile in my consciousness today is not the same as it was when I was 20 years old. Exile is not the same on the global scale that it was half a century ago when the word was perhaps born into this world of sorrow and pain.

It seems that this concept will have a long life, so long as people fail to find solutions other than wars and exploitation to resolve their problems with the other—whether that other includes humans, animals, nature or the vast universe itself. No matter what it is, we do everything we can to subjugate it.

Exile Papers by the well-known Syrian writer and novelist Haidar Haidar was the first book I read about the topic. In it, he discusses his experience with exile, writing and life. Today, more than two decades after I read Haidar’s book, he now lives in Syria once again after returning decades ago. I am the one who has now left the country, towards what others call “exile.”

The paradox is that Haidar Haidar returned to his country before the fall of the dictatorship, living under its shadow in a remote village on the Syrian coast, itself almost a sort of exile. Strangely, we haven’t heard a single word from this famous novelist about what is happening in Syria. Is this the price of returning home?

The entire architecture of my life had been built around living in Damascus.

These words are not meant to judge Haidar Haidar or his stance, but rather to shed light on the question: What governs our decisions to return? Why should we go back home anyway? Haidar wasn’t the only one to have returned from exile in the 1980s, though there are those who returned and remain engaged in politics in every meaning of the word.

How does our exile today differ from the exile of Haidar Haidar’s generation? Are we fated to return to Syria like them, or will we follow in the footsteps of others, who have decided never to go back home at all?

Back when I read Exile Papers, my idea of exile was romantic, just like my idea of home. Until a month before I left Syria, I never thought of leaving. I had never considered emigrating or living outside Damascus, a city I adore, despite my love of travel. The entire architecture of my life had been built around living in Damascus and travelling two or three times a year to countries I love, always returning home afterward to work, live and write, to settle there permanently.

But at some point, I started to feel differently. Maybe it was from reading, or observation or just life experience. My knowledge of my own country expanded, and I began to realize that the place I had called home was nothing more than a big prison. It swallowed up people for many long years in prison cells, the keys held by a ruling junta that steals everything, starting with our resources and extending to our freedom to speak, criticize and write.

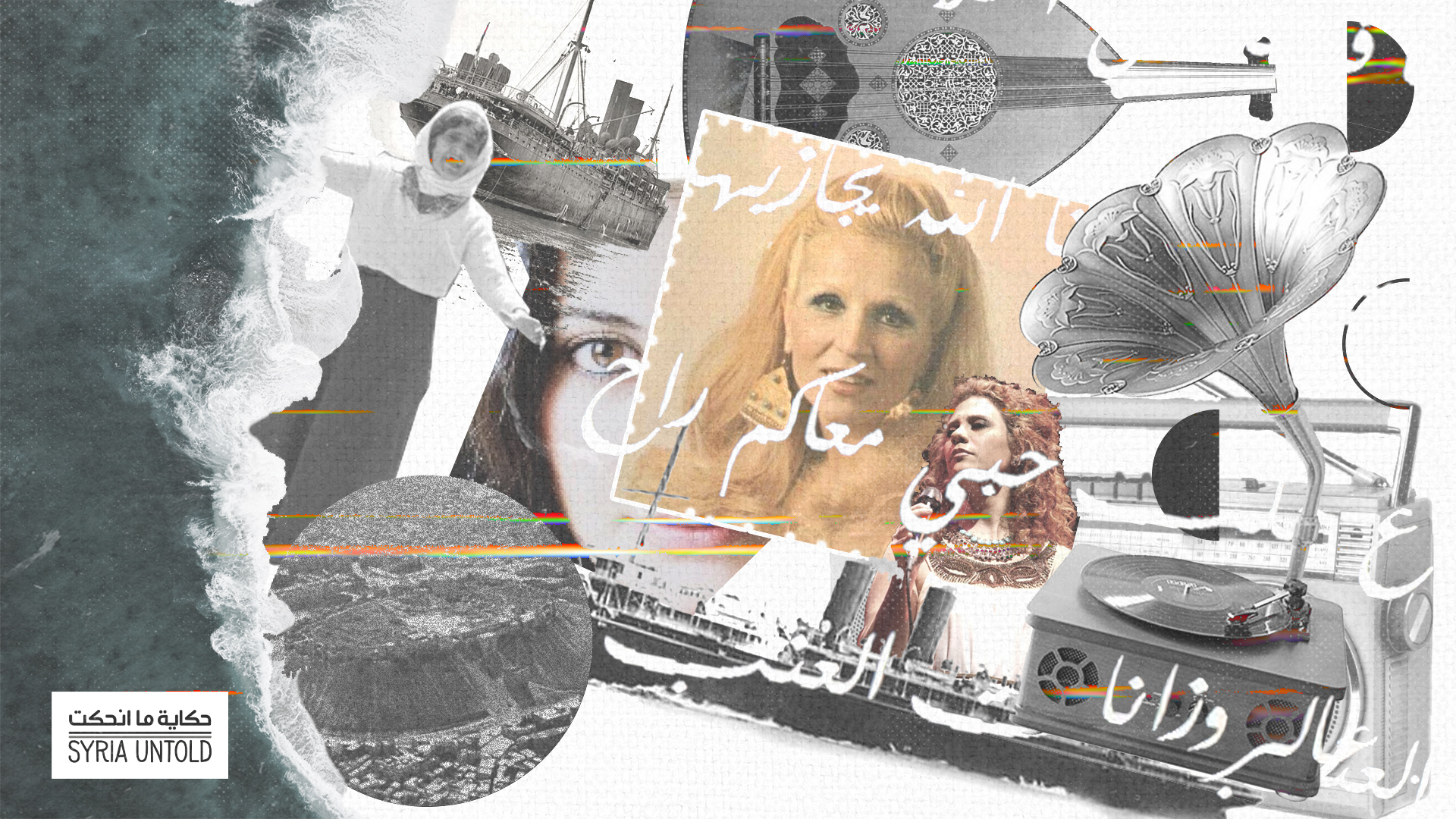

Songs of nostalgia in New York City’s long-lost ‘Little Syria’

05 March 2021

Because I chose writing and journalism as my profession, every day I came into contact with restrictions that I could not actually write about in my own country. Day after day the idea of home changed for me, from a beautiful and beloved place to someplace difficult and restrictive. And yet I was determined for the time being to stay, to expand the space for freedom and cultivate hope in its barren soil.

At the same time, in my mind and memories, exile was a remote and strange place. It was where the persecuted were forced to seek safety from arrest or death, where they were embattled by a daily longing for a lost home, family, a familiar space. It was the sense of nostalgia that we read in their books and articles, smuggled back home to Syria, which made the idea of exile to me something both tempting and repulsive. I was tempted to experience the freedom that these exiled Syrians spoke of, and repulsed by their nostalgia and distance from home, their painful experience of loss.

When the Syrian revolution began, the whole world began to change around us. And in those first months of the revolution, it seemed to us that Syria was the whole world. Those still in exile prepared to return home, and those still in Syria were determined to keep staying, hoping to see the moment that freedom shone over a country of tyranny. But little by little, as the various paths of the revolution faltered, and people began escaping the brutal violence and arrests, an exodus began to occur in the opposite direction. People searched for temporary safety in neighboring countries, places where they could wait things out until the eventual fall of the dictatorship.

It didn’t occur to those who left in those first few years that they would continue to remain in exile, that those temporary refuges would become permanent. Has our main concern become the search for a permanent, stable exile? And yet, aren’t the words “exile” and “temporary” more or less the same? Exile is meant as a temporary state, no matter how long we stay in it.

Beirut in our imaginations had been a city of dreams, legends, freedom, appetite, desire. But living there made me see its other face.

I was finally forced to leave Syria in the summer of 2014, after a long period of stubbornness and insistence on staying. It reached the point that my friends who had already sought refuge elsewhere were asking me: “When are you leaving?” I’d answer them: “To where?”

At the time, the idea of leaving Damascus hadn’t yet entered my mind, despite all the dangers and difficulties of staying. I remember that until June 2014 I hadn’t thought of leaving at all, and then all of a sudden, within the space of one month, I changed my mind completely and decided to leave. Why did I make this change, and how?

My perception at the time of the shabiha and regime personnel trawling the streets of Damascus after the 2014 “elections,” acting with the confidence and arrogance of the victor, may have played a role in my decision to leave. Their mocking smiles robbed me of whatever remained of my hope, resilience and ability to change from within.

From Damascus’ al-Rawda cafe to Berlin’s Einstein cafe, a heartbeat

28 August 2020

Sultana’s story

10 July 2021

Now, as I write these words, I remember meeting a Syrian-Palestinian doctor who had been living in Germany for three decades. He told me he decided to leave Syria in the 1980s after an encounter with security forces, who had heard him say critical words toward the regime. He felt humiliated, besieged by the question: Will I really spend the rest of my life bowing to these people? He answered his own question, deciding to leave Syria with no regrets. To this day he says he feels no regret.

As I contemplate my own reasons for leaving Syria, and my conversation with the doctor, I wonder: When does someone finally make the decision to leave their home country? When the injustices at hand impact their dignity and become unbearable? But what is the limit of dignity, and who defines it? Did I really leave my own country because my resistance had been exhausted?

When I rearrange things in my mind, and I look back more calmly, I see that my reaction towards those regime soldiers’ arrogance in 2014 was merely the straw that broke the camel’s back. Despite my stubbornness, the decision to leave Syria had grown in my soul over time. I was living under fear getting arrested a second time, under the pressures of a difficult day-to-day life. Maybe the decision grew invisibly, like a weed that grows in the shade. I stayed in Syria under the guise of courage, a desire to remain in a homeland that was no longer livable.

When I arrived in Beirut in the summer of 2014, I didn’t feel any of the symptoms of exile. No nostalgia, no longing, no desire to return at all. I felt no stress, other than something my mother had told me over the phone: “You left Syria and left us on our own.” Then came the nostalgia for some places in Damascus: the cafe on al-Rawda street, al-Salehiyeh, Bab Touma, the alleyways and noises of Jaramana. But otherwise, I spent just a short time immersing myself in this new place, and already I began to find that I saw exile as better than being home. Syria itself was the land of exile and not the other way around. It was a frightening exchange of roles.

In Beirut, I started finding and reading all the banned books. I read any newspaper I wanted whenever I wanted. I wrote what I wanted to write. I talked in cafes with my friends about everything and insulted the regime and its allies without fear. Gone was the censorship that used to live inside me, and with its absence, my views changed. I began to see things from many different angles and retreated from some beliefs I once held close to me when I was in Syria.

Which of us is truly in exile: me, who now travels everywhere and reads everything, or my friend, imprisoned within the borders of their homeland?

I discovered the extent to which tyranny exerts pressure on our thinking and limits our ability to develop. To live under daily fear and anxiety means to drain your energy on everyday things, on censoring yourself and your own words even when you claim to do the opposite. Even your access to sources of knowledge and what goes on in the world are limited, no matter how hard you try. In the end, it all means that tyranny is able to restrict the frameworks within which our minds move, even if we claim to be free of them.

Discovering this led me to also have a critical eye towards Beirut, which hardened from a sort of heaven into reality, with all its contradictions, fragility, ugliness and beauty. Beirut in our imaginations had been a city of dreams, legends, freedom, appetite, desire. But living there made me see its other face, negative, brutal and restricted. Strangely, this didn’t diminish my love for the city. Beirut for me remained beautiful and warm, a city that resembled none other. Isn’t there beauty in imperfection?

The biggest transformation in my relationship with exile was in Berlin. If Beirut was a regional city, cities like Berlin, where I currently live, and Paris, which I love, are truly global. They make you look at Damascus and Beirut from another position in the world. You begin to test your questions and your knowledge in light of your new experience, rediscovering exile and homeland. You realize that cities are nothing more than huge villages in this vast world, from the northern hemisphere to the south.

A famine, a ship and a folk song that spanned borders

18 December 2020

Land, revolutions and lessons from Syria

04 May 2021

Your feelings are only reinforced when you observe the world’s biggest issues from your new place in it. Issues like climate change, migration, the rise of right-wing ideology in the West, Islamist extremism, coronavirus. You read about your own region and your struggle against dictatorship in your country and in the Middle East all while you grapple with these global issues. Before, your struggle back at home was the only issue you were concerned with, the issue through which you view the rest of the world. But today you view your struggles as just one part of the larger struggle that the world faces, and you rethink things through this framework.

Here you rediscover exile and home. You confront the same questions but from another place. Which of us is truly in exile: me, who now travels everywhere and reads everything, or my friend, imprisoned within the borders of their homeland? Me, who is constantly able to expand my awareness, or my friend, restricted in their ability to access information and interact with others? What remains of the idea of exile when people of the Global South move northward, fleeing homelands that serve only as prisons?

Within this context, today I don’t feel the weight of exile at all. I feel like a global citizen, that I can live everywhere and anywhere. The world is my home, and I am concerned with all its different issues. Today I live in Berlin. Maybe tomorrow I’ll live in Paris or Khartoum or Cape Town, or even Damascus, though not simply because it is in the country of my birth. I’d live there because I love it.

Wasn’t the world like this in some form before the modern concept of the state with all its troublesome borders? Couldn’t some traveller 200 years ago ride their camel or sail their ship off to new places, unimpeded by borders? Maybe we could return to a world like that, one in which the entire globe could be our home. Words like Syria, Germany, France, South Africa and Europe would merely be specific points within that vast human vessel. When, then, would remain of exile?