RAYAK, Lebanon - Acacias grow between railroad tracks headed nowhere. A lonely train car sits in the surrounding field, abandoned in a hurry half a century ago. Only patches remain of the locomotives’ green paint. The bullet holes and graffiti reading “Syrian Army” inside one of the cars hint of dark days past.

In the Lebanese Beqaa Valley, five kilometers from the Syria border, the Rayak train station feels like a majestic skeleton. In Ottoman times, it became the biggest railway repair workshop in the Middle East, fixing the locomotives that T.E. Lawrence and the Arab revolutionaries sabotaged while fighting the Ottoman empire. In its golden era, Rayak’s train platform bade farewell to travelers heading to Beirut, Istanbul, Damascus and Baghdad. Later, it became an intelligence base for the Syrian army.

And, for 47 years, the station was home to Asaad Namrud.

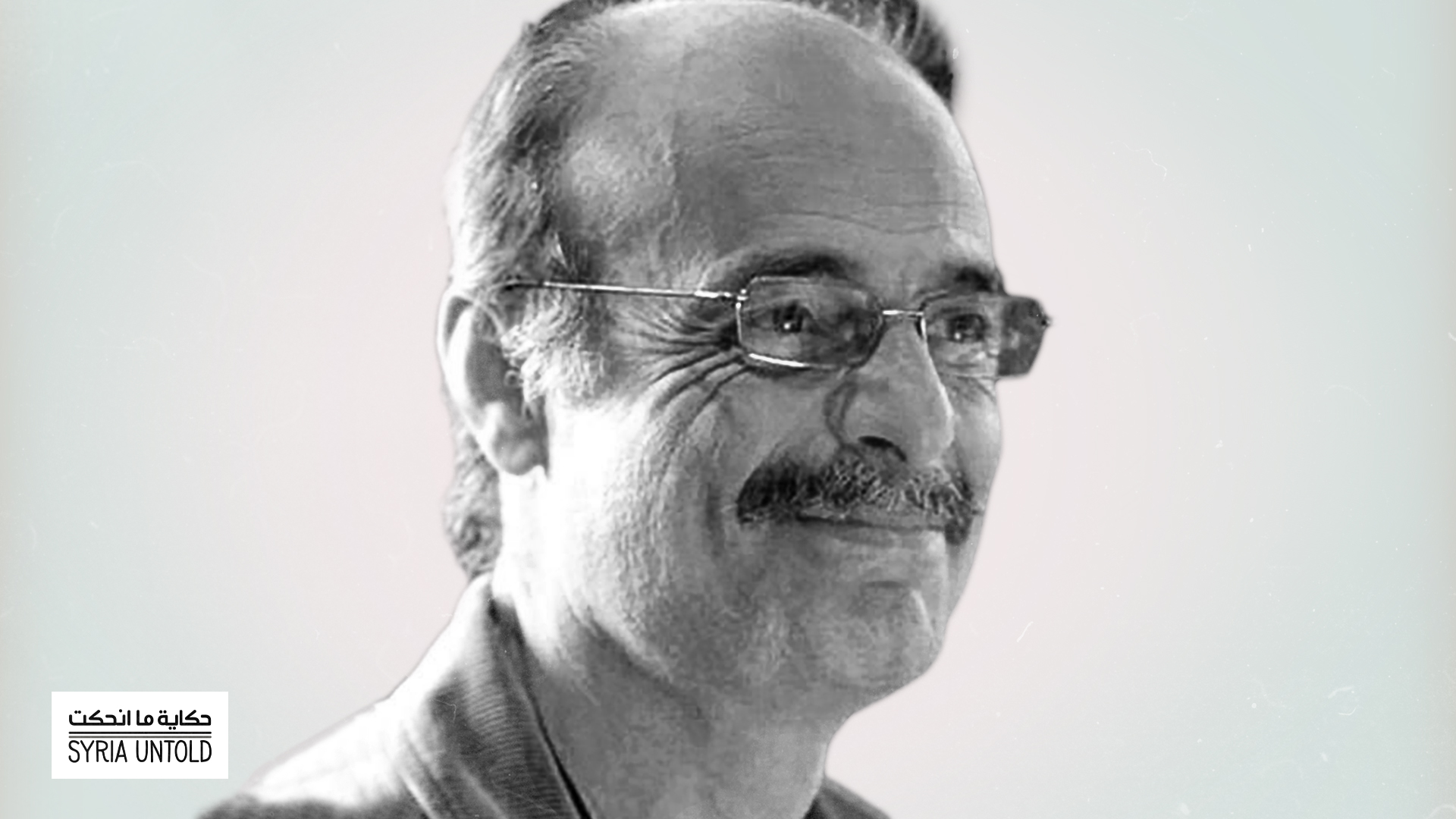

On a warm autumn morning, 94-year-old Asaad is busy chopping onions for a stew in his modest home in Rayak, a few steps away from the train station’s remains. The only decorations in his living room are a painting of a rail track, an old photo of his locomotive and his train driver license.

From Ottoman Syria to Argentina

02 August 2021

A famine, a ship and a folk song that spanned borders

18 December 2020

In 1976, a year into the civil war that would drag Lebanon through the next decade and a half, Asaad drove the train from Beirut towards the Syrian border. “I brought 800 goats from Beirut to Rayak. It was my last trip,” he remembers. Once he stepped out of his locomotive, no steam engine roared again along the Beirut-Damascus line. It was the end of the railway.

That decline had been a long time coming. The first train in the Damascus-Beirut line set out on August 3, 1895, inaugurating rail travel in the Levant. In 1911, Tripoli in northern Lebanon got its train station, connecting the city to Syria’s Homs and Aleppo. In the first half of the 20th century, passengers hopped on in Beirut and commuted to Damascus, Istanbul, Baghdad, or even further afield to Mecca after connecting to the Hejaz Railway line. As civil war erupted in the 1970s, however, the Lebanese railway was left to rot. Syria’s aging train line followed a similar fate after 2011.

Now abandoned and left to rust, the railways that once crisscrossed Syria and Lebanon tell a story of what could have been. It is a tale of nostalgia and missed connections; but also, of quixotic battles in a quest to connect a disconnected region.

The last train driver

When a teenaged Asaad announced that he was dropping out of school to work for the railway, his father slapped him in the face. Soon after, Asaad found himself shadowing a French engineer in the Rayak station. “It was the time of General de Gaulle, and the French were in charge of the railway,” he says. At the time, in the early 1940s, Lebanon and Syria were under French mandate.

After four years learning the trade, Asaad officially became a train driver. Jordan, at the time a British protectorate known as Trans-Jordan, was his first destination. “It was a two-day trip. I left Lebanon and slept in Damascus. The next day I headed to Jordan and then back to Damascus and then the Beirut port, where they unloaded the merchandise like porcelain,” he recalls.

“You saw a train carrying cargo or passengers every 10 minutes,” remembers Asaad. In winter, trains couldn’t get through the mountains around Dahr al-Baidar, part of the range separating coastal Lebanon from the Beqaa Valley further inland. Instead, they’d take the train that rode through the tunnel. “We were underground for 20 minutes, and we had the mountain on top of us. It was pitch black!” He’d burn his hands stoking the fire in the steam engine.

The rail became his life. “I drove to Daraa, Homs, Damascus, Turkey, Tripoli, Beirut and to the border with Israel,” Asaad says. He recites the distances between stations like a memorized lesson: “from Rayak to Homs, 85 km; from Rayak to Damascus, 80 km; from Damascus to Jordan, 70 km; from Aleppo to Turkey, 75 km.”

It was a two-day trip. I left Lebanon and slept in Damascus. The next day I headed to Jordan and then back to Damascus and then the Beirut port, where they unloaded the merchandise like porcelain.

His trips would sometimes last a month, keeping him away from his wife and six children. “Whenever I arrived at the Rayak station I would whistle—you could hear it from the mountains to the sea—and my wife knew I was back.”

Songs of nostalgia in New York City’s long-lost ‘Little Syria’

05 March 2021

Book preview: Ottoman Syrians at home in the American Midwest

05 October 2021

In the early 20th century, the Beirut-Damascus line connected to the Ottoman-run Hejaz Railway that passed through present-day Jordan, and continued southward through the desert to Medina. The Taurus line connected Beirut to Istanbul via Tripoli and Aleppo. From Istanbul, the Orient Express took passengers onward to Europe. French, Polish, German, American and Swiss trains crisscrossed the region. At its peak, the Rayak station employed 2,500 workers, explains Elias Maalouf, author of the book Lebanon on Rail. Beirut and Damascus were connected to the world.

Given the economic and military power the railway entailed, colonial powers France and Britain fought to be the ones to design it. However, according to Maalouf, it was Youssef Motran, a businessman from near Baalbek in present-day Lebanon, who first obtained the privilege from the Ottomans to build the Beirut-Damascus line in 1891. He later sold construction privileges to the French.

“Rayak was better than London, there were so many people here,” Asaad says. Carefully, he opens a box of old photos. In a picture dated 1973, Asaad poses with a blonde woman. “She was the daughter of the boss of the railway in London and asked to ride with me in the locomotive. I told the assistant to clean the seat and I gave her my jacket.” He then browses the photos in Lebanon on Rail. In the last pages, a young driver stares stoically into the camera. His name was Fares Garabet.

The sunrise rides

Fares Garabet’s grandson, also named Fares, lives in Germany after fleeing his home in Damascus six years ago.

The elder Fares was of Armenian origin and lived in Damascus. Like Asaad, he joined the railway when he was a teenager, faking his ID and upping his age by two years to be able to work. The plan succeeded. He drove trains from Rayak during the 1930s and 1940s. Later, his son also became a train driver.

With the end of the French mandate and the independence of Lebanon and Syria, the railway company Damas Hama and Prolongement (DHP) was split along the border between the two nations; the Syrian government expropriated its share, the Lebanese bought theirs. Trains and workers were also divided.

“My grandfather faced the choice of staying in either Lebanon or Syria,” says the younger Fares, speaking over Skype from Germany. “He preferred to go to Damascus and work on the Syrian railway in the 1970s and 1980s, and later he was employed as warehouse head.” Some of his grandfather’s relatives, however, stayed in Lebanon. Part of the family became Lebanese and the other Syrian. The elder Fares died in 2017, in Syria.

I saw the farmers working the land, the birds singing, the smell of the steam going out, the sounds of the whistle… it was such a beautiful scenario, I won’t forget it in my life.

Today only an aunt remains in Lebanon, while most of the family in Syria has left for Canada, France, Germany or Australia. Fares fights to keep memories of the once-united family alive.

“In summer, we used to go to my aunt’s house in Beirut. These were the best days of my life. Syria was a closed country, while Lebanon was open.”

Sultana’s story

10 July 2021

Within the margins, and breaking free: Syrian cinema

23 January 2021

His quest to preserve railway heritage in Syria materialized in 2000. Fares proposed to the then-Minister of Transport—who happened to be a friend—to create a museum in Damascus for the old steam trains. The museum later became a reality, reigniting old memories. “My father used to show me the traces of bullets in the trains my grandfather used to drive, which were attacked by Syrian revolutionaries.”

His most adored memories are the trips between Damascus and Serghaya, a quiet mountain resort town and the last stop before the Lebanese border. His father let him sit next to the driver’s seat in the locomotive. They would ride the three hours from Damascus to Serghaya, sleep there, and head back early in the morning. “My father used to wake me up at 4 am, when the train was cold as snow.” Once heated, the train would depart at 5 am to bring the workers and traders to Damascus around 8 am. “I saw the farmers working the land, the birds singing, the smell of the steam going out, the sounds of the whistle… it was such a beautiful scenario, I won’t forget it in my life.”

‘Soundtrack’ of the Tripoli-Aleppo line

Nassif el Murr's most vivid memory of his days as a train driver is the soundtrack of the engine. “The sound of the steam going out in the mountains was more beautiful than the best music,” says the 93-year-old former train driver from his home in Tripoli.

Nassif’s journey on the railway started in 1947. A year later, in the war that followed the creation of the state of Israel, Israeli forces bombed the railway line between Naqoura, in southern Lebanon and Haifa, in Palestine, that had been built only six years before. The bombing foreshadowed the violent borders that would come to shatter railway aspirations.

Still, Nassif’s dreamed of becoming a train driver. That dream had to wait 12 years, which he spent as a depot assistant. Then, in the early 1960s, he became the driver of the Beirut-Homs line. He still has the details of the route memorized. “The train to Homs was at night, and the train to Beirut was during the day. It could take four hours and the speed limit was between 30 or 35km per hour.”

Nassif used to drive the German G8 locomotives that were part of a “looted gift” to Lebanon from the Allies after Germany lost WWII, according to Nabil Doumani, a Tripoli train enthusiast and vice president of an NGO aimed at reviving Lebanon’s railways. Three of these gigantic locomotives now sleep at the abandoned Tripoli station, relegated to “vintage” backdrops for wedding photoshoots. Nassif can’t bring himself to visit the station; the disrepair is too painful. He drove his last train in 1971, then he became a supervisor in the railway’s Tripoli office.

From his days driving to Syria, he remembers turbulent times. “Every two weeks there was a coup. During the Amin al-Hafiz era, I got stuck in Syria with the train during one of the coups,” he recalls. Al-Hafiz was a former Syrian president overthrown in 1966. Since Syria’s independence until Hafez al-Assad’s ascent to power in 1971, military coups were frequent.

I can go with my car to Byblos, but it is not the same as sitting with someone of the ‘other kind,’ talking, working, making fun, falling in love.

The split along the border between Syria and Lebanon complicated Nassif’s drive. “When the railway company was one, it was easier; there were Syrian employees in Lebanon and Lebanese in Syria.” After independence, Nassif would have to stop at a station five kilometers into Syria and exchange the locomotive with his Syrian counterpart. “You had General Security on the Lebanese and the Syrian side, it took time, they inspected the train, the passengers and the cargo.”

Agatha Christie and a lost blanket

Arda Kashkashian doesn’t remember the border inspections; she was only a young child when she rode between Tripoli and Aleppo. Split between both cities, her family members were regular passengers on the route.

With Armenian roots, Arda’s family settled in Aleppo over a century ago. In the late 1960s, after one of many coups in Syria, the schools stopped teaching French and English. The family decided to move to Tripoli. “Lebanon was more open and more democratic than Syria,” Arda says.

Arda, now 59 years old, works as a psychologist. She lived in Tripoli until two years ago, when she moved back to Aleppo after losing her savings to the financial crisis gripping Lebanon.

Arda’s father, Jean, had a carpet business in Aleppo and Tripoli, so the family would commute often. “The trip was really long, it was very boring for me, and I had nausea,” she remembers. “I was just a kid.”

Arda giggles, though, when she remembers “the blanket” incident. The family used to spend their summers in Hadath al-Jebbeh, a town in the Lebanese mountains. One summer, disaster struck: they forgot Arda’s favorite blanket in Aleppo. “I didn’t sleep for two or three nights, I was crying.” Her father had little choice but to ask the train driver, Manuel, to bring the blanket with him from Aleppo to Tripoli. “My mother then went down to Tripoli, took the blanket and brought it so I could sleep and stop crying.”

This is a dream, and some dreams never come true.

Arda’s family history is also linked to the main train station in Aleppo, called Baghdad Station for the journeys its locomotives would take eastward to the distant Iraqi capital. When her father was six years old, his own father would send him to the train station to attract incoming travelers to the family’s small hotel.

Years later, Arda’s father became the director of the storied Baron Hotel, she says. It was high-end, built to attract glamorous foreign travelers at a time when Aleppo was a bustling commercial hub. Agatha Christie stayed at the hotel and wrote part of Murder on the Orient Express there. The opening scene of the mystery classic is set in the Aleppo train station.

Hala Abdullah: 'I believe in cinema as a means of resistance’

11 June 2021

Randa Baath: 'Any cultural act is vital'

12 March 2021

Goodbye trains, hello cars

Riding the steam train through the snow. That’s a fond memory for Walid Kamari. For 42 years, his father drove trains from Beirut to the border with Syria. From there, Walid’s uncles drove the trains through Syria on to Turkey. The Kamari family, like many others, were scattered across borders. Walid’s grandparents were born in Turkey, his parents in Aleppo, and he in Lebanon.

Walid remembers riding in the locomotive with his father “more than 10 times” as a child. “He told me how the machine worked. They were lovely days, especially during the winter seeing the snow,” he recalls. They would travel often to Aleppo to visit relatives, and Walid remembers the antics and the foods sent from Aleppo to Beirut. “There were a lot of passengers. Syrians used to visit the snow in the Lebanese mountains.”

His last trip on the train was in 1969, he says; he was 15 years old. After that, cars took over.

The first time Georges Said rode a train was due to a coup d’état in Syria. He was a young teenager in Aleppo, and, alongside other youth in the city, was “invited” to attend a festival organized in Damascus by then-president Adib Shishakli. “He wanted to show that he was popular,” Georges says. “It took us 30 hours. We did 350 km, we slept in the school, we stayed there three days, saw the thing and we came back to Aleppo by train.”

Sometime after that, Georges’s family left Syria, ending up in Beirut. “Lebanon was the best at that time, it was the Switzerland of the East.”

The family would take the automotrice, a diesel engine train, between Aleppo and Beirut often, up until 1963 when they got their first car, an Opel. That year was the last time he visited Syria. Now 84 years old, Georges owns a hardware store in Beirut’s Mar Mikhael neighborhood.

“I have not been back to Syria. I am not with any political party, but I don’t like the Syrian regime, I like free governments,” he says. His Syrian relatives visit him in Beirut, he adds, not the other way around.

Rayak and the universe

Elias Maalouf was born in Ecuador with a “virtual door to Lebanon.” His parents had fled Rayak early in the Lebanese Civil War, and were prone to overdosing their children with nostalgia. “We were brainwashed by our parents to love Lebanon. All we dreamt of was coming back to Lebanon, to Rayak, the city with the biggest train station and air base in the universe,” explains Elias from his home in Rayak. As a child, he often imagined the town’s old cinemas, souks and, of course, the train station.

The Maalouf family returned to Rayak in 1991, after the war’s end. It had already been 15 years since the trains there had gone silent. “We only saw dust, goats and old sad people dreaming of the past.”

Elias, 11 years old at the time, asked his father about the old cinemas; they were now potato storehouses. Only traces remained of the old souks and an ice cream factory. When he asked about the train station, his father was adamant: “You are not allowed to even look at the train station.”

The Syrian army, after entering Lebanon in 1976 invited by president Suleiman Franjieh, had “overstayed” after the end of the war. The Rayak train station—and adjacent air base—became their intelligence base, where “they used to mess with people,” says Elias. Naked detainees would be crammed in the rusty train cars “during the summer and winter,” says Elias, who has gathered dozens of testimonies from former railway workers and residents of Rayak. “In both cases it was bad,” he adds.

For Syrian victims of the Beirut port explosion, a year of grief and rage

03 August 2021

The options for Syrian female activists in Lebanon: Fear, imprisonment or departure

22 May 2020

In 2005, following the assassination of Lebanese Prime Minister Rafic Hariri, the Syrian army withdrew, and political divides in Lebanon deepened. That year, Elias was finishing his studies in documentary filmmaking, so he decided to document the withdrawal of the Syrian army from Lebanon. “Rayak was the last place in Lebanon they left,” he says.

So he sneaked into the railway repair workshop. “It was like Disneyworld: big old rusty trains, beautiful colonial French buildings, hundreds of wagons!” Suddenly, his parent’s wistful tales of home seemed real. “I realized my parents were telling the truth when they told us about the city of Rayak. For the first time, I really believed them.”

Elias says he saw three Syrian soldiers guarding a train car. Smoke was coming out. As they left, Elias sprinted towards it. “I saw beautiful old archives being burnt, and I tried to save some.” But as he did so, he burnt his hands; by instinct, he shouted. The soldiers, noticing his presence, shot in the air. He says he hid and watched as the soldiers returned to the railcar to keep watch until the documents had all been burnt. He could only save a handful of the papers.

For Elias, this day marked the beginning of 15 years of activism to preserve the railway heritage and bring trains back to Lebanon, including founding the NGO Train/Train. They tried to build a museum in Rayak like the one in Damascus, but Lebanese authorities were not interested.

Elias connected with other train enthusiasts in Lebanon and Syria. “For a certain funny period of time there was this debate of who had the best station: Rayak or Tripoli?” Then they united their efforts. “I fell in love with all the train stations in Lebanon. Our voice was loud, our mission was written in newspapers around the world, everybody read about it except the politicians in Lebanon,” Elias says.

Elias has been forbidden to enter any train station in Lebanon since 2012, amid a public spat with Ziad Nasr, president of the Lebanese government’s State Railway Authority. “I didn’t allow them to sell the old parts of the train as metal scrap,” he explains. When asked if his ban could also be related to the time he sneaked into a train station and managed to drive a locomotive for a few meters, he shrugs the idea off with a smile.

“First they laugh at you, then they fight you, then you win,” says Elias, reciting a quote often attributed, albeit mistakenly, to Gandhi. When he first talked about a railway comeback in Lebanon, “people used to laugh at me, I was Sancho Panza, then they fought me, and I became Don Quixote.” After 15 years in activism, Elias has taken a step back. He now spends most of his time with his family and on his vineyard in Rayak.

“I didn’t get to the part where I win.”

Long night to resurrection

05 February 2021

The chapter of decay

Nabil Doumani rolls his eyes as he walks into the Tripoli station and sees a pair of newlyweds posing for a photo next to a corroded G8 locomotive.

Six locomotives, three French and three German, sit in the station, which remains unfenced. “These are not the original locomotives that were here in 1911 when the station opened,” Nabil, vice-president of Train/Train explains. “Those locomotives are probably in Syria.”

Nabil’s grandfather was one of the Tripoli businessmen who originally gave funds to build the station. Nabil’s only trip on a train in Lebanon was in the mid-1960s, when his mother asked the driver of a cargo train from Tripoli to nearby Chekka to let her kids enjoy the ride in the last train car. They did enjoy it. “Trains are not a hobby, but a passion,” he says.

From the window in the abandoned depot, a bunch of rail tracks are left to decay. “These rails were bought by the Lebanese government in 2002, brand new rails,” he exclaims. Back in 2002, there was an attempt to reconnect Syria and Lebanon by railway and funds were allocated to build the 35 km of railway track between Tripoli and the Syrian border. But then in 2005 Rafic Hariri was assassinated “and the whole project stopped.”

Politics, once again, blocked the railway. But decay on the Lebanese side can be also attributed to inner policies. “From 1961 until the start of the civil war, the Lebanese government did not add one meter of railways to the network. They just managed it and then let it die,” explains Nabil.

First, the 1960s witnessed the “car revolution.” Trains felt outdated. And in Lebanon in particular, authorities had an appetite for the real estate value of railway properties. “Lebanon's main economic policy is investment in land and service. When you view land as a commodity, you will do anything to prioritize real estate profit over anything else. This came at the expense of public space and public transport,” explains urban planner Abir Saksouk.

By the early 1970s, when the government announced its decision to close the railway, its workers–one of the strongest syndicates–paralyzed Beirut, blocking the main roads with trains. “The government realized they couldn’t stop it, so decided to let it die. Every time a worker retired, no one replaced him,” says Elias.

Can the trains come back?

Excited, Carlos Naffah narrates to a camera about how he is driving a historical locomotive (from 1948) from Sissach to Geneva, in Switzerland. Next to the video, posted to his Facebook page, is the caption: “Together we will bring back #Lebanon_on_track.”

Carlos defines himself as a “train maniac.” He says he hasn’t forgiven the neighborhood kid who broke his green train toy with six batteries. In 1995, while in school in Beirut’s Daura neighborhood, Carlos remembers watching a green and yellow train chug by a couple of times. “It was a Polish SU45, introduced in Lebanon in 1971,” he says. Although trains stopped at the onset of the civil war, around 1984 there were sporadic freight routes between Beirut and Jounieh, Jieh and Zahrani. And after the war, between 1994 and 1996, a few trains hauled cement from Chekka, just outside Tripoli, down to Beirut.

In 2018, Carlos became the president of the NGO Train/Train. “I fell in love with our heritage. I could see the potential to reconnect the country.”

With Syria ravaged by a decade of war and Lebanon plunged in an economic downward spiral, talk of trains may seem a bit out of place. And yet, Carlos’ dream of reviving the railway goes beyond transportation.

“Lebanon is destroyed not only economically but socially,” Carlos says. He sees Lebanon as patches of socially disconnected communities. “People in the south have never been in the north, and people of the coastal side have never been in Beqaa.”

A decade on, how can we work to free Syria’s detainees?

16 April 2021

My childhood friend, now a ghost

18 September 2020

“What would connect the Lebanese people together, and Lebanon to everybody else would be the train,” adds Carlos.

On the other hand, reconnecting Beirut to Damascus is tricky. Carlos argues that countries with complicated histories have been able to maintain their trains. “Between the former Soviet Union and Norway, borders were closed, but the train was still connecting them with special security measures. It should be possible to reconnect Damascus to Beirut, or Homs to Tripoli, even if we need to apply complicated security measures.”

“Trains can build peace between cities because people will have the chance to move, to get in connection,” Carlos adds.

Elias feels similarly. “I can go with my car to Byblos, but it is not the same as sitting with someone of the ‘other kind,’ talking, working, making fun, falling in love," he says.

Where would you go if the trains returned?

If he could, Walid says he would take the train to Aleppo. Fares, retracing his grandfather’s and father's steps, would ride from Damascus to Rayak. Nassif, the former train driver, would visit Beirut.

While Georges, the hardware store owner in Mar Mikhael, ponders his imaginary trip, his neighbor Norma Irani wanders in from the street. Her father Fuad used to sell tickets for the Beirut-Damascus line in the early 1940’s, so she jumps in. “It is very important to have a railway—imagine going from here to Syria or Iraq. In half an hour you could be in Damascus,” Norma says.

“What is up to you with Damascus? I am only interested in trains inside Lebanon,” says Georges.

“It’s just an example. I would like to do tourist things in Damascus, Homs or Aleppo. I used to bring shanklish from Syria, it was so good,” says Norma, referring to a type of aged cheese popular in the Levant.

“You go to Syria, I stay in Zahle,” says Georges, ending the conversation. Zahle is a city in the Beqaa Valley.

Arda, the psychologist who rode the Aleppo-Tripoli line as a child, would take the route again and “see what comes back” to her memory. But, she adds, “this is a dream, and some dreams never come true.”

“The obstacles are too great, but it is very important to be able to imagine the possibility of a different life,” says Abir, the urban planner.

That possibility seemed, momentarily, to materialize in August 2019, when Train/Train presented their proposed railway national master plan for Lebanon. The system would connect to Syria via Damascus and Homs. “People in Damascus will be able to be in Beirut in 40 minutes for their weekend, people in Amman can go to Beirut in an hour and a half to have a meeting and then go back to Amman,” explains Carlos.

Only two months later, anger over a government plan to charge for WhatsApp usage morphed into massive countrywide protests over the state of Lebanon’s political and economic system altogether. As protestors called for a new government, the country began sinking into its worst financial crisis in more than a century. Two years on, the local currency has lost most of its value and even the most basic needs such as electricity and medicine are difficult for most people to come by. Carlos says Train/Train has met with possible investors from Spanish, French, German, Italian, Chinese and Swiss companies. But prospects are bleak. “We cannot invest anything if the chaos continues, we need reform and accountability,” he says.

And yet, somehow, the quixotic dream seems to persevere. Carlos remains optimistic. “Our train will go from Naqoura in the south to Aboudieh in the north, passing all cities along the Mediterranean Sea. It will be one of the most beautiful trains in the world,” says Carlos.

Asaad, the last driver of the Beirut-Damascus line, still retains his passion for trains after all these years. When asked where that love comes from, he is quick to answer: “Trains are the path to freedom, they only go forward.”

Editing by Madeline Edwards