SyriaUntold is publishing this article as part of the #ForJustice campaign, in partnership with the Institute for War and Peace Reporting. A version of this article was first published in Arabic here.

“I often tried to talk to my husband to figure out why he absolutely resented me. After repeated rejections, he told me honestly: ‘I can longer come near you. I cannot even look at you. I don’t know what happened to you in prison, and nothing can guarantee that nobody has touched you’,” Aliaa*, a former detainee, recalls.

When she was in prison, Aliaa often dreamt of the moment she would be released and could return home. Now in her early twenties, she was arrested as a teenager in early 2015 by the Air Force Intelligence Directorate in Damascus, due to her media work.

“When I was in prison, I always thought about my parents and their situation. I dreamt of holding my children close, like any prisoner does. I impatiently waited for the moment of my release. I endured the physical and psychological pain and stood my ground just to be able to see my children again,” she tells SyriaUntold.

Aliaa remained in prison for about six months, and was released by the end of 2015. She was hoping her community would welcome her, especially since she was arrested due to her media and political stances, which she considers honorable. But, upon her release, she realized her husband had rejected her.

Life after prison: Society chasing survivors

Long night to resurrection

05 February 2021

Prison: Writing versus experience

27 February 2020

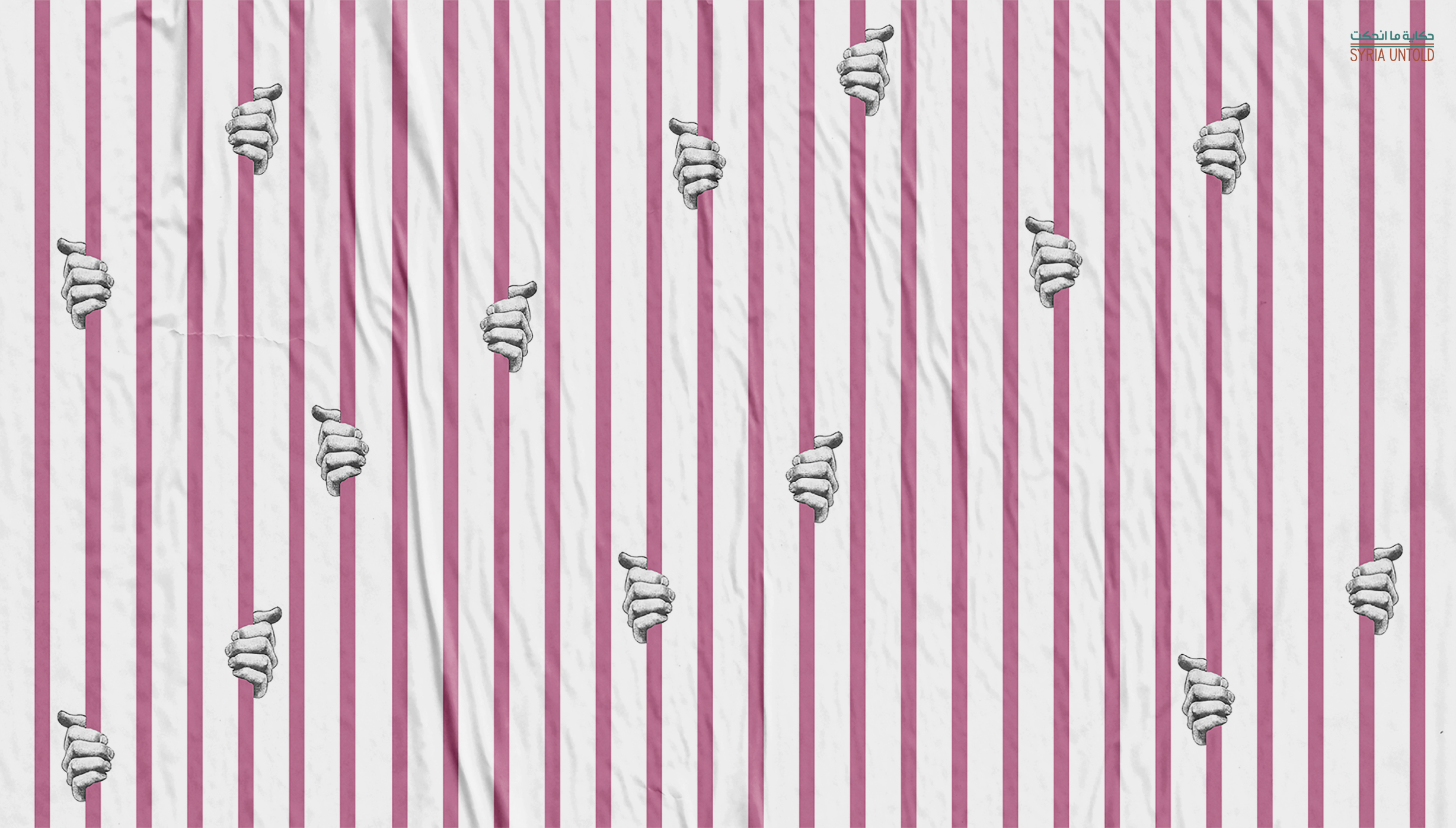

A decade after the outbreak of the Syrian revolution and ensuing conflict, virtually every political or military party has detained activists and media figures. The Syrian government is responsible for the majority of arrests against women, in particular. A report released last year by the Syrian Network for Human Rights counted “no less than 9,668 women remain held up or forcibly disappeared by key actors in Syria between March 2011 and March 2020, including 8,156 detained or forcibly disappeared by the Syrian regime forces.”

Following her release from government prison, Aliaa wished she had not been let free. She realized that living with her husband and restoring their relationship would be impossible. It would be difficult for her to endure the social stigma of being a former detainee, and the constant questioning by those around her.

She wasn’t alone. A 2020 report by Women Now, a Syrian women’s rights organization, found that many women survivors of Syrian detention have faced backlash from their communities following release from prison.

“A key experience shared by the majority of survivors...was the violent reaction to the experience of detention by both close and more distant members of their communities,” according to the report. Some survivors were reportedly forced to marry, or put under house arrest by their family members “to wash away the shame.”

Aliaa felt she needed to separate from her husband because he was harsh towards her. Now 23 years old, she still works in media and lives with her children outside Damascus. She is trying to mend the “broken pieces” inside her—those shattered by her detention first and her husband’s cruelty later.

My body is not for exploitation

Wissam* was arrested in Deir al-Zour in 2013, for her work in the human rights field. The following year, she was transferred to Adra prison near Damascus, then released by the Counter-Terrorism Court following reports written about her supposed ties with the Free Syrian Army (FSA).

If a man wants to propose to one of my sisters and finds out I was detained, he changes his mind.

She says that her parents and close friends from her primary social circle were supportive, but her relatives and acquaintances blamed her for her arrest.

“My parents are facing a lot of pressure, and they are the ones who have paid the price. We are six girls and one boy. If a man wants to propose to one of my sisters and finds out I was detained, he changes his mind. This always perplexes me because I was the one detained, not my sister!” she tells SyriaUntold and the #ForJustice campaign.

In a 2015 report on women detainees in Syria, the Euro-Mediterranean Foundation of Support to Human Rights Defenders found that members of female prison survivors’ communities tend to stay away from them and their families.

“Due to the stigma associated with rape and sexual assault [that often occur in Syrian detention], people tend to stay away from families of current or former detainees. As a consequence, detained women are often shunned by their communities or families after their release,” the report noted.

After Wissam’s release, she tried to go on with her life: she had only two university exams left to obtain her diploma. But she was not safe from men’s permissive and intrusive attitudes towards her body.

“I was standing with my university friend when a strong wind blew and displaced my scarf in a way that showed a bit of my shoulder. As he tried to fix my scarf in its place, I told him I did not like anyone touching me. He retorted, ‘You still haven’t forgotten their touches in there, have you?’ I was shocked, and I could not speak. I usually have my answers ready, but I was too shocked at that moment. I still remember it, and I do not know what to say. I have no idea what sort of feeling overcame me. Was it disgust or hatred? I do not know. It was a mixed feeling, and I was very hurt,” she says.

“I felt that some people were treating me like violated property. They thought that, if I am a former detainee, then I was definitely raped and ready for sexual intercourse. Men often made passes at me and insinuations to engaging in sexual acts with me. Others thought that, since I was a former detainee, men might want to marry me to cover up for my shame and I would owe them for that."

The body, between event and memory

25 January 2021

A Syrian visiting a Nazi camp

25 September 2019

Wissam now lives in the southern Turkish city of Sanliurfa, where she and other female survivors established the Syrian Women Survivors Organization, a political and rights group. They are reaching out to other survivors to make their voices heard and advocate for both female and male survivors by offering social and economic empowerment activities.

‘I am proud of my daughter’

In 2012, detainee Alaa Morelli appeared on Syrian state television under the pseudonym Binan al-Hassan. The government had forced her to do so. They broadcast an exclusive interview with her, under the pretext that she had previously made false statements to Al Jazeera. She was arrested when she was still a university student, and handed a ready-made charge.

“After I appeared on television, people started visiting us,” Alaa remembers. “My father supported me. He stood up in front of everyone and stated in a loud voice that I was on television, and that he considered me a heroine.”

In 2013, a pro-regime channel aired a documentary of three female detainees: Sara al-Alou, Fatima Faroukh and Ferial Abdul Rahim. They were forced to talk about performing “sexual jihad with armed men from the opposition factions.”

The regime also broadcast an interview in 2014 with Rawan Kaddah, who was only 17 at the time. Dubbed “A father selling his daughter’s honor,” the episode showed Rawan talking about her father coercing her into having sex with fighters from the opposition factions. Granted, Rawan only said these things because the Syrian regime forced her.

The Syrian Network for Human Rights documented in a 2015 report how the Syrian regime forced 11 women and girls to “confess” on state television that they had sex with opposition fighters upon their parents’ request.

The Syrian regime’s practices constitute a violation of international norms, as Protocol II, an addendum to the Geneva Conventions, prohibits mutilation, torture, harsh, offensive and inhuman treatment of detainees, taking of hostages and unfair trials.

My father supported me. He stood up in front of everyone and stated in a loud voice that I was on television, and that he considered me a heroine.

Talal Mustafa, a sociologist and researcher at the Harmoon Center for Contemporary Studies, says that dictatorships often practice systematic violence against women because they realize the nature of some conservative societies, including Syrian society. Security forces, he says, detain women not just to torture them, but to demoralize their communities as well.

“It is a matter of inherited traditional values that reduce women’s role to carrying the values of honor and chastity. According to the public mindset, even if the woman is not harassed and raped in jail, the mere fact that she was detained puts her behavior in question,” Mustafa adds.

Alaa now lives with her husband and five children in Antakya in Turkey, and works with the Syrian Women Survivors Organization.

Over-care is not the answer

Sahbaa al-Khodr is a psychologist working in cognitive behavioral therapy. She says that part of her therapy for female survivors of detention consists of re-empowering them to face society’s perception of them and enable them to enter the job market and improve their relations with their relatives.

It is also important to enhance their self-image, and to try to integrate them in society, especially due to the changes they have to face, like separation from their spouses or deprivation of their children or parents.

“I hope that, when dealing with female survivors of detention, there is no exaggeration in caring for them, or that people don’t bombard them with questions," al-Khodr says. "It is enough to treat them as women who suffered a certain experience due to the war, but who survived in the end.”

*Some names have been changed to protect the safety of interviewees.