In the early days of Syria’s war, Modar Shekho, a medical technician, received two injured children whose family home had been hit by a government air strike. It was 2012, in a part of Aleppo city that had been captured by rebels. In response to the capture, government forces bombarded the district indiscriminately.

The children faced life-threatening traumatic brain injuries and needed urgent care.

Dar al-Shifaa Hospital, where Shekho worked, was the only functioning hospital within opposition-held east Aleppo that could take them in that day, he says. But a medical device that he needed in order to treat the injured children was out of service. “We had to send the kids to Turkey for a CT scan,” Shekho recalls.

The journey wouldn’t be easy. The Turkish border was about 50 kilometers north, and after night fell, the route was completely dark. “War planes were flying overhead and targeting all the cars that were using their lights,” he says. “So the cars were driving by moonlight only.”

Though they didn't realize it at the time, they were living through the beginning of several years of heavy fighting, air strikes and siege within Aleppo city. Shekho and his colleagues prepared bomb shelters as the months and years of bombardment wore on.

For young Idlib doctors who treated war wounds, COVID an invisible new threat

02 October 2020

How do you explain hunger to a child?

08 January 2021

Syrian government forces would later go on to destroy Dar al-Shifaa. Six bombs, dropped from a Syrian war plane, leveled the hospital. Shekho then moved to the al-Daqaq Hospital, in another neighborhood of east Aleppo. Later, in 2016, that hospital was severely damaged as well. By December, east Aleppo was recaptured by the government, and remaining residents and fighters were bused out.

But years before all that, Shekho and his colleagues needed to figure out what to do with the two children who had been brought to Dar al-Shifaa with severe head injuries. They’d need more intensive care, ideally across the border in a Turkish hospital.

Ambulances had already become the target of armed groups. So the team had to drive unmarked, down dark roads with the headlights off, listening above for the sound of aircraft or drones.

They got to a bend in the road. “With the darkness and the speed of the car, [it was easy] to imagine an accident happening, one that nobody would survive.”

Documenting a decade of war crimes

Last month, Syrian Archive, a project of Berlin-based human rights documentation group Mnemonic, released a massive report detailing more than 410 separate attacks on 270 medical facilities in Syria since 2011. Many, like Dar al-Shifaa and al-Daqaq, are in Aleppo. Others are scattered across the country, red dots on a map marking the location of each targeted facility. The vast majority were likely attacked intentionally. Open source data used in the report paints a grim picture of how armed groups not only hit hospitals, but also targeted medical teams themselves with multiple, clustered air strikes, drone surveillance and then return strikes.

While Syrian government forces and their Russian allies carried out the majority of attacks, Syrian Archive curated evidence that nearly every other group, including the opposition, majority-Kurdish forces, Turkey and the Islamic State hit medical teams as well. The primary difference? The Syrian government and Russia use advanced technology guidance systems and carry out repeated precision attacks while the other groups have tended to hit medical teams in more directly combat-related single strikes.

In seeking protection from the bombs, many of the targeted facilities had previously shared their coordinates with the UN, as part of an oft-criticized “no-strike” list shared with warring parties, including Russia.

Syrian Archive’s report is the latest in a series of large-scale investigations by international media into a decade of attacks on Syria’s medical infrastructure. In each case, investigators, human rights advocates and journalists have argued that the international community has enough access to evidence about armed groups—on multiple sides, but primarily the Syrian government and Russia—to take action, as well as to hold attackers accountable to international humanitarian law.

Artino Van Damas is a Syrian photojournalist and press officer for Mnemonic, the NGO responsible for Syrian Archive. The new report stands out, he says, as it provides not only a pre-curated collection of open source leads for international war crimes investigators to pursue, but it also provides analysis that could aid the United Nations and security organizations to reevaluate two policy questions.

First, medical teams were encouraged mid-war to provide their locations to the UN for its “no-strike” list. The hope was that warring parties would avoid hitting those sites. However, armed groups continued to target them, forcing medical teams to move their facilities to reinforced or underground locations, and in some cases hide their medical wards in safe houses, relying on unmarked cars.

Second, Van Damas explained, Syrian Archive provides data which could help the international community prevent armed groups from using a technique of “double-tap” aerial and artillery strikes. With these tactics, armed groups hit the target once, wait for rescue workers to arrive, and then strike again to target those who have arrived on the scene to help.

Children at war: Reliving photos of east Aleppo

25 September 2020

In pictures: COVID-19 on the rise in northwestern Syria

14 November 2020

Still, for Syrian medical workers like Modar Shekho and his peers, who struggle to save lives while being targeted for doing so, these reports have not yet motivated the international community to help them beyond rare small provisions of medical supplies and advice.

While international advocacy has not worked, medical workers and humanitarian agencies like Humanity & Inclusion, the Center for Civilians in Conflict, Mayday Rescue, Doctors Without Borders, the Syrian American Medical Society and The Syria Campaign instead rely on such reports more for improving civilian protection and self-protection methods on the ground. There is little other choice, as the attacks on medical facilities have continued unpunished. Using the detailed data, civilian protection advocates may be able to shape safety plans, not to prevent attacks or damage as a whole. They may not be able to halt aerial and artillery strikes by warring parties, but at least they can shape their strategy of survival, as the thinking goes.

And the attacks are far from old news. Late last month, government forces fired artillery shells on a hospital in Atareb, a town in rural Aleppo governorate. Six people reportedly died, including a child.

‘No training at all’

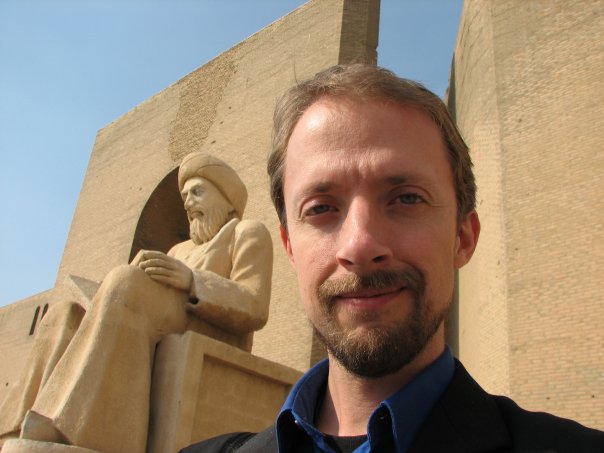

In 2011, Dr. Wassel al-Jark, a surgeon from Maaret al-Numan in Idlib governorate, was treating people who had been injured by government forces while participating in pro-democracy demonstrations.

While shifting between three field hospitals over the next years, he found that armed groups were not only fighting each other and their political opposition, but appeared to be directly targeting hospitals as well. He and other medical workers had little choice but to radically change safety measures in order to survive attacks.

“When there is bombing, we evaluate the location, so we don’t leave patients in a facility on the front line,” says Jark. “When someone arrives injured, we do first aid, then send them to a safer place. We take preventative measures and stay in a more fortified place, for example, or we change the location every day or two because there are always reconnaissance aircraft in the air.”

Medical workers learn many sounds when targeted, Jark recalls. Above one’s heartbeat, the accelerated breathing, the slipping of feet on broken glass on the hospital floor, the squeaking of gurneys bringing in the latest patients, the screams of a patient with a head wound, one must also listen for the sound of incoming aircraft, drones and explosives.

“They spot ambulances,” Jark says of the drones. “Can you imagine? One time there was bombing on the village where the field hospital was and there were reconnaissance aircraft in the air. They watched where the ambulances went and after a short time they targeted our [medical building] as well. I saw and lived this. And many times the ambulance itself was targeted.”

There was “no training” for such attacks, Jark remembers. “The training for us, as a medical staff, was only how to deal with injuries. But when it comes to fortification, security and safety measures there was nothing.”

COVID-19 reveals the reality of governance in Syria

07 November 2020

A Syrian visiting a Nazi camp

25 September 2019

Qusay al-Ali is a former nurse at the al-Daqaq Hospital in Aleppo city, though now works in another location. “Unfortunately, safety training did not receive the necessary importance, or [rise] to the level of the violent attacks we were subjected to,” he says.

Al-Daqaq was hit numerous times and destroyed during the opposition’s flight from Aleppo in 2016. Over the years, hospital staff witnessed their original safety training tips—marking medical sites and staff to be avoided by armed groups, relying on the main building equipment, and using bomb shelters—become obsolete.

By the end, they often had to do quite the opposite of what they learned in training: avoid marking medical sites and ambulances, divert most patients away from the main hospital building and remain painfully aware that sometimes bomb shelters only work for lighter explosives like mortars—not for barrel bombs, which can trap people underground.

“We used to work in the basements of the hospital,” Qusay explains. “It was a way to avoid these ferocious aerial attacks. Unfortunately, the weapons used were affecting even the bomb shelters. Often we would transfer patients to buildings far from the hospital because we were not safe from sudden attacks.”

Medical teams now often designate safety staff to focus on communications and information which can help anticipate threats. “Spotters,” a role described in the Syrian Archive’s report, as well as by medical staff who spoke with SyriaUntold, listen to radio frequencies, make calls, and listen outside to deduce whether armed groups have changed positions or aircraft are above.

Their observations provide an “early warning” net to give medical workers a brief window of time to go down into the bomb shelter for smaller explosives like mortars or, potentially, to evacuate and spread out to other buildings in case of a missile or barrel bomb, which could penetrate a bomb shelter or cave.

“These health facilities should be transportable,” Qusay says, “or their departments be built apart. Even if a part of them is destroyed, the rest of the departments can transfer patients to a safe place. What I mean is, with the distribution of hospital departments over a large area of land and the distribution of patients to them, the losses will not be so heavy.”

Trainers and spotters explain to medical teams how armed groups have patterns which can help predict threats if they are understood, but could lead to greater tragedy if ignored. For example, armed groups often “bracket” their artillery, firing a first shot to get close to the target and then using that blast location to adjust the aim of the weapons and then fire again for full effect.

In response, some aid groups have urged against keeping medical staff and patients in one central place clustered together. As part of safety measures that physicians of the past would have considered absurd, many teams now run “stealth” medical units: quiet, spread out and unmarked. And any patients in need of more complex care are sent quietly to the Turkish border.

“From my experience,” Shekho says, “these organizations [that suggest safety protocol] might include people who have lived these ordeals in their training, to convey views based on their own experiences.”

“It is so hard to describe in papers or books,” he says, remembering the night in 2012 when he rushed the two young children from Aleppo city to the Turkish border for urgent care. He and the team drove without headlights to evade detection. Beforehand, he never imagined his medical work would become a stealth operation.

He remembers reaching the border after some time. The parents would later send their thank yous, and the children would receive treatment and recover at a hospital in Turkey.

As for Shekho, he turned back around to Aleppo, returning to help others still trapped under the bombs.

With translation support from May Khairy.