SyriaUntold first published this investigation in Arabic in 2020 as part of the “Syria In Depth” project, in cooperation with International Media Support (IMS) and the Guardian Foundation.

“Detention is expensive. If you have a detainee [in your family], it means that the same officers who are responsible for your pain enjoy your money" the father of one Syrian detainee said to SyriaUntold.

Ismael Ali, a 32-year old man who was arrested in Damascus in 2012, said that he feels “an indescribable guilt" over the effect his detention had on his family.

“My already-poor family had to pay $6,000 to secure my release from Saydnaya prison. This destroyed my family’s livelihood and ruined the futures of my two younger sisters,” he said.

This investigation focuses on the economic dimension of the mass detentions and forced disappearances in Syria. Our findings reveal the existence of an expanding market surrounding these arrests. For “sale” in this market are notifications of prisoner status, procedures and judicial rulings. Their buyers are families desperate to find their children, and their peddlers are middlemen and lawyers who offer inside access and information to Syria’s prison system for a premium. And of course, those who profit off this system are officials in the government’s security and judicial institutions.

Tens of thousands of Syrians have been arrested since the start of the Syrian revolution in 2011. Most were arrested as a result of their participation in political or civil activities.

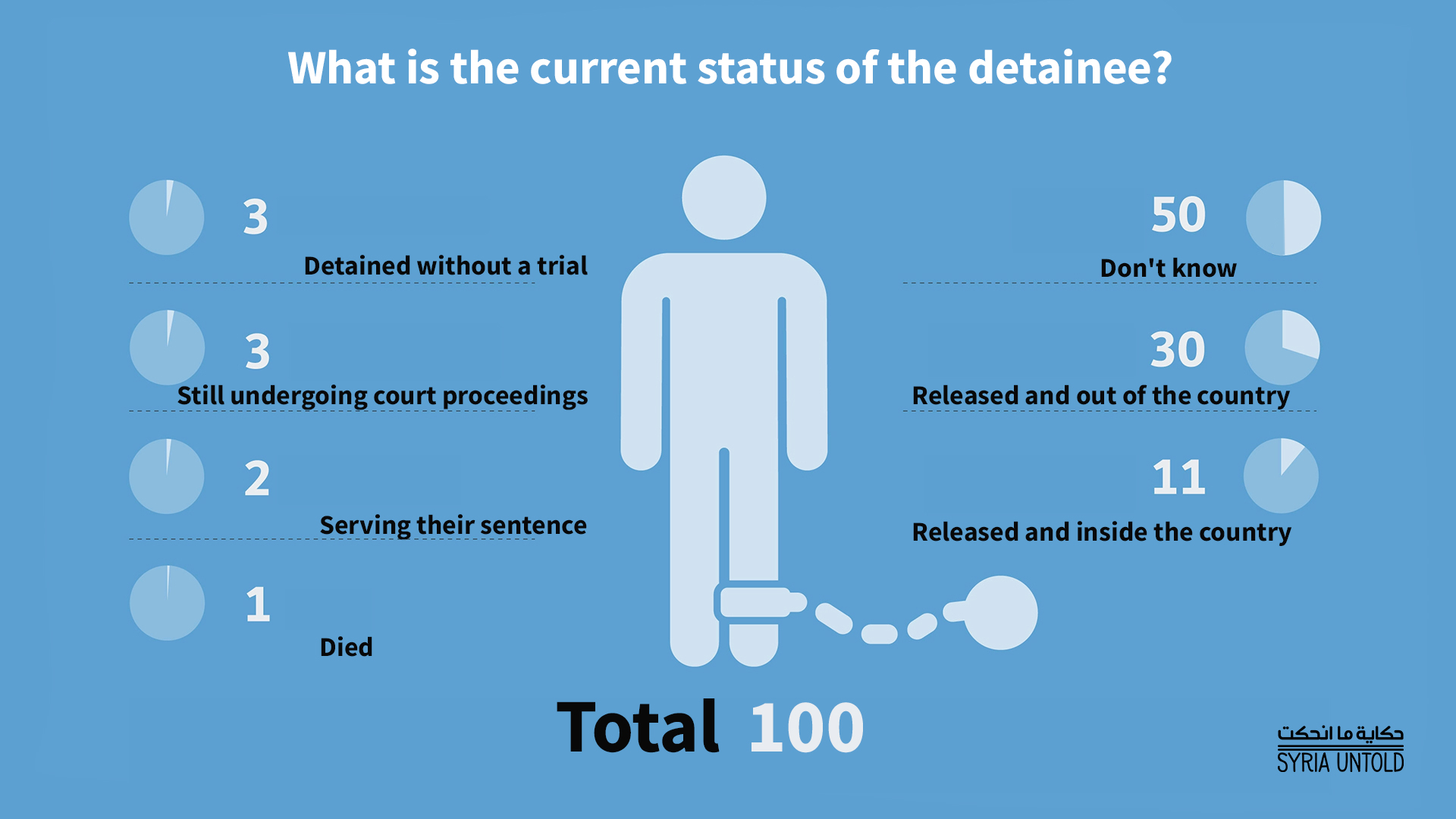

SyriaUntold investigated 100 cases of detention for this article, reaching interviewees via the snowball sampling method. The only criteria for each case was that the concerned person had been detained by one of the regime’s security services or its forces. Consequently, the interviews—conducted in Syria and Turkey—were diverse in terms of backgrounds of the detainees and disappeared, the charges leveled against them, and the outcomes of their cases.

All 100 of the cases examined in this investigation were either discussed with the detainees themselves, or in cases where the detainees died, were discussed with their families. Some 85 families reported that they were either subject to financial extortion, or received demands of payment. Of those families, 75 ended up paying what was asked of them. Combined, these families made 160 payments to Syrian security and judicial bodies. Some families only made one payment, while others were forced to make between two to seven payments.

The average value of payments made was about $5,000, while the total value of all payments made was nearly $800,000. It is worth mentioning once again that this sum is from only 75 families. This means that each detainee or disappeared person cost their family over $10,000 on average.

The family that made the most payments was one where three brothers were arrested at the same time.

“My family first started paying to find out where we were being held, then they made repeated attempts to have us released, then finally they paid to have us transferred to a court,” one of the three brothers told SyriaUntold. “After five years of detention, our family then sold what was left of their possessions to purchase convictions for us under the charge of terrorism, as that was the only way we would be let out.”

Mending what has been broken

12 February 2021

Long night to resurrection

05 February 2021

Rami (not his real name) a 30-year-old father who was arrested in Homs in 2013, said that his family paid around $40,000 in total during his detention. This amount, while staggering in the context of Syria’s dismal economic situation, is not the largest amount found in our investigation.

Where does it all begin?

From the moment that someone is arrested or kidnapped, their family in one way or another becomes part of the economic market of Syria’s prison system. At first, families will have no idea whether or not their relatives and children were detained or forcibly disappeared, as detainees are cut off from the outside world and the security or military agencies which arrested them do not inform their families that their relatives have been arrested.

None of the 100 families we investigated received a written or verbal notification of their relatives’ arrest—with the exception of one family.

After the arrest and the family’s realization their relative is not coming home, they have two options. The first is to pay members of the security services, whether directly or indirectly, in order to get information about their relative or relatives. The second is to wait for another detainee to get out of prison, so that they might tell the family the whereabouts and condition of their loved ones.

Most of the time, families resort to the first option, desperate to pay any amount of money to save their children from the hell of regime prisons—a reality they were well aware of before Caesar’s photos revealed the truth to the rest of the world. However, these payments don’t always help detainees in the end.

In one such case, Majd Khoulani, a well-known peaceful protester in Daraya, a western suburb of Damascus, was arrested by the regime in 2011 after the arrest of his older brother, Abd al-Sattar.

Ghafran, a sister of the two Khoulani brothers, told SyriaUntold: “Each week we would go out, my mother and I, searching for Majd and Abd. We would submit requests [for information] at the military court and to the Ministry of Interior, and stand for hours in front of the security branch in hopes that we would catch a glimpse of one of them as detainees were being moved.”

“My father was a trader and was ready to pay millions just so that they could be moved to Adra civil prison so that we could visit them—but this was all in vain. All the lawyers and mediators we turned to withdrew from the case once they knew it concerned a group of peaceful activists in Daraya. Many of them withdrew only after taking money from us.”

About a year and a half after Majd and Abd’s detention, their family was allowed to visit them in the Saydnaya military prison—a facility described by Amnesty International as a “human slaughterhouse.” Of course, the visit didn’t come cheap. The family had to pay a huge sum to see the two brothers.

At the same time, the security forces had arrested even more members of the family. They arrested two more brothers—Bilal and Mohammad—one sister—Amina—her husband, and another sister’s husband. This brought the total number of detainees in the family to seven.

Amina, who was arrested in March 2011, was another well known activist who eventually went on to be awarded the US State Department’s International Women of Courage award in 2020.

“Until we were forced to leave Syria in 2015, searching for and trying to secure the release of the family’s detainees was our constant concern,” Ghafran said. “I don’t know the exact amount of money that we paid during that period, but it was a huge amount. It was useless in the cases of Majd, Abd and Mohammad.”

The family was finally able to rescue Amina and her husband, and Bilal and his sister’s husband in 2015. The remaining three brothers died under torture.

Pictures of Mohammad surfaced as part of the Caesar photos which leaked in 2014. Still, the family maintained their hopes that Majd and Abd would be returned to them, until they received a civil registry document in 2018 that said that the two brothers had died five years previously, in 2013.

When neither rights nor laws are respected, paying bribes is all that can be done. Our data reveals that about 42 percent of payments made were by families attempting to locate their children.

At the same time that families are attempting to locate their children and secure their release, those very same children are facing horrific forms of physical and psychological abuse designed to push them to confess to pre-fabricated charges. Most detainees do not go to court until they’ve already confessed to these charges.

It is at this stage that the fate of the detainee is decided—whether or not they will remain a disappeared soul, or will turn into a detainee in one of Syria’s many prisons.

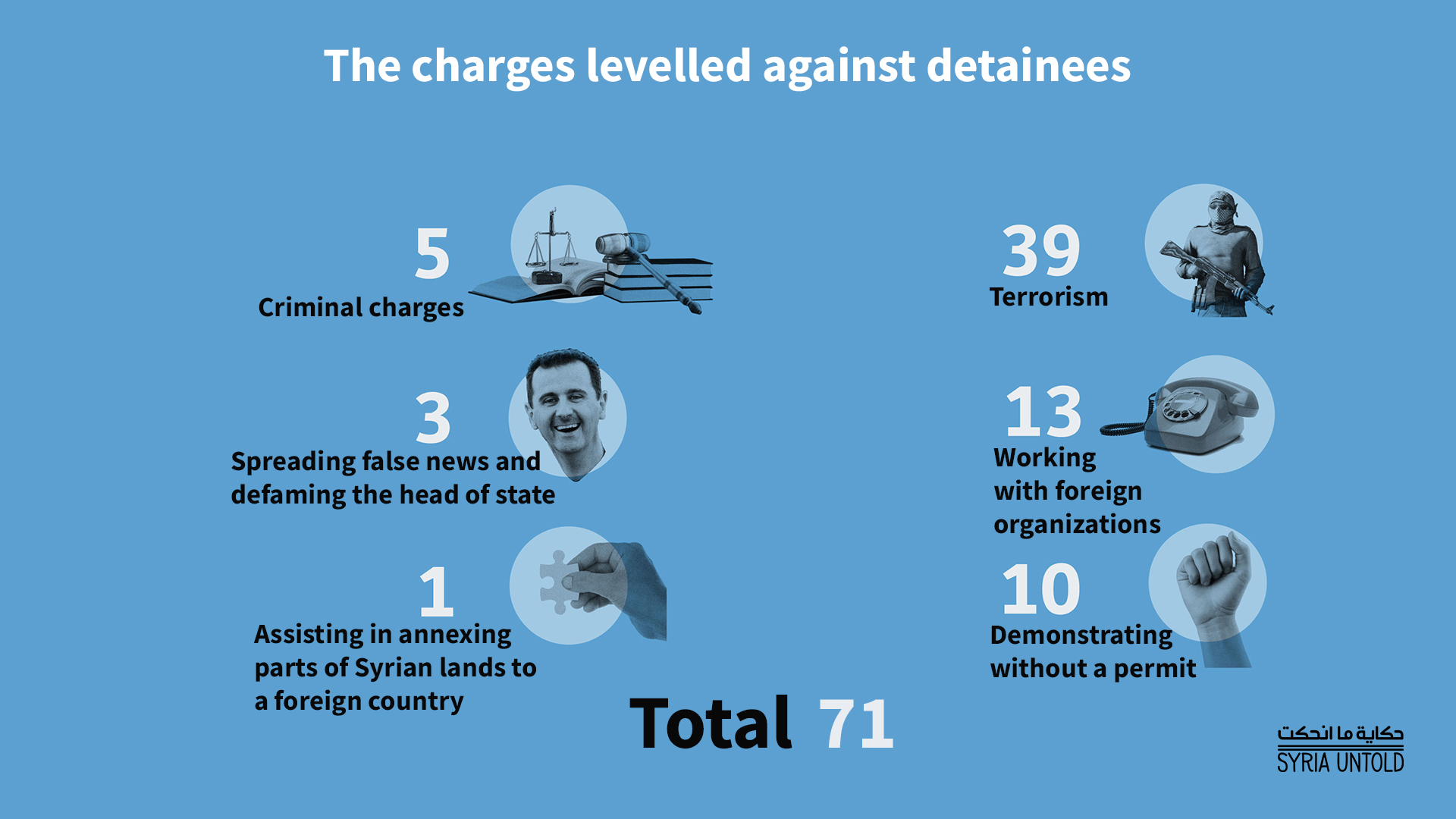

Those lucky enough to have been turned into a detainee often arrive at court carrying confessions of serious crimes, which will in turn, require them to pay, again, a large sum of money. From the 100 cases examined in this investigation, 71 ended up as detainees, while the rest remained forcibly disappeared.

The following infographic outlines the charges levied against the 71 detainees:

Most of the 71 detainees reached court, or at the very least, their whereabouts were specified by the regime. Before they reached court, detainees were typically transferred between different security branches in different governorates, a process that could take anywhere from months to years. In those cases where detainees became detainees, detainees were moved between security branches two to nine times.

On average, detainees were moved three times before they reached court. Generally, each new place meant facing a different set of charges and new, creative ways of torture—and for families, each move meant a new round of bribes had to be paid.

Still, relative to their fellow detainees whose fates are only known by the stained walls of their cells, those who reached the courts were the lucky ones.

“Not all detainees have their files sent to the public prosecution office. There are those that disappear completely,” Riyad Ali, a former judge who worked in Damascus before defecting in 2013, told SyriaUntold. “The security services are stronger than the Interior Ministry and Ministry of Justice. As judges for example, we are not able to enter the prisons of the security services,” Ali said.

Which are the most prominent security directorates carrying out detentions, then?

First and foremost, the Military and Air Force Intelligence directorates play the biggest role in carrying out arrest campaigns and forcibly disappearing people. These two agencies are affiliated with the General Intelligence Directorate and are directly linked with the president, according to Ali. These two security agencies were responsible for nearly half of the detention cases we investigated.

The other half of the cases investigated were distributed among other security services, such as the State Security agency and Political Security. Finally, 10 people from our sample were arrested by pro-government militias, such as the National Defense Forces (NDF) and other groups referred to in Arabic as the shabiha. Notably, no cases were arrested by the police.

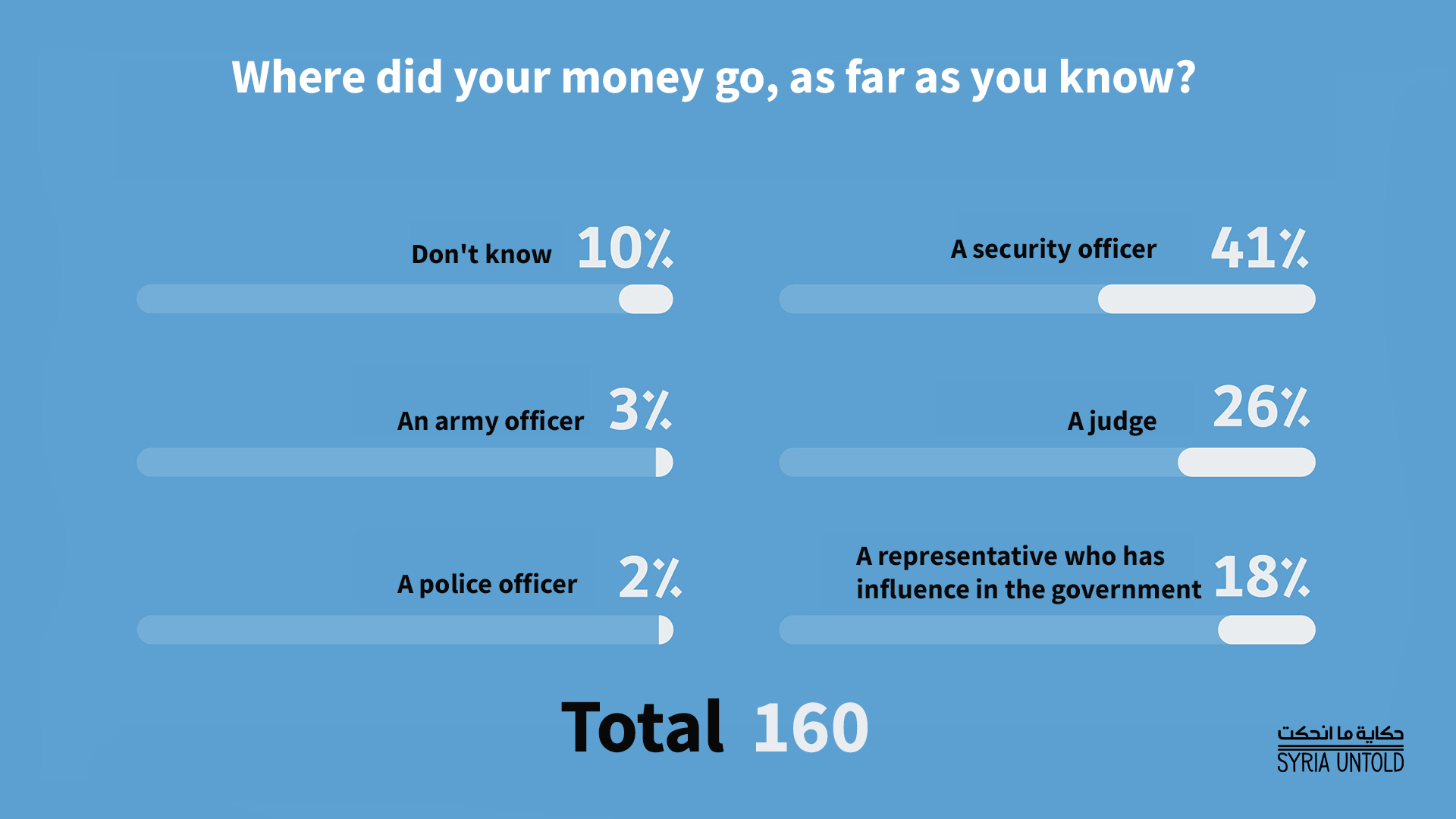

Who is being paid? How do these payments reach their destination?

Families rarely communicate directly with corrupt security or judicial officials. Rather, the payment process is facilitated by a network of middlemen who are dubbed locally as “keys” (mafateeh in Arabic). Each judge or officer has one or more key. It is these middlemen who families turn to when they need help locating their relatives. The key will sometimes tell families to whom they will be sending the money. Other times, the families have to put their trust in the men, and have no way to confirm that their payment ever actually reached the security or judicial services.

There are three types of intermediaries operating in this network of “keys.” The first are “brokers,” who are civilians with connections to government officials. Then there are junior employees in the security and judicial establishment. Finally, there are lawyers who help facilitate these payments. Of all the payments made by families interviewed for this investigation, 46 percent went to brokers, 25 percent went to lawyers, and about a quarter went to employees in the security and judicial establishment.

The breakdown of payments helps shed a light on how deeply entrenched this prison economy is across all sectors of Syria. However, realities on the ground might be even more complex than numbers reveal. Sometimes mediation is done through personal networks, and families start searching for relatives and acquaintances who have relations with officials in the system.

This search will lead them from one intermediary to another until they reach someone who has knowledge of their relative’s case. This process of referral from one intermediary to the next is especially important in cases of prisoners who are moved to different governorates.

However, in some cases, intermediaries might reach out to the families on their own initiative and request money from them.

A former detainee who is now living in Turkey, but still has a relative detained in Syria, told SyriaUntold about his experience being contacted by a middle man. “Even until now we are being contacted by someone who is close to the regime. He tells us that our relative is in Saydnaya, and he is close to death and needs $5,000 to be released. But how can we trust this person, someone who we don’t even know?”

The whole process of making payments on behalf of detainees is shrouded in mystery. Families do not have any guarantees that their payments will reach the intended recipients, nor do they have any recourse if mediators decide to defraud them.

Mariam Hallak, the mother of the doctor and activist Ayham Ghazzoul who was forcibly disappeared in Damascus in 2012 and later tortured to death, said that a lawyer requested $13,000 from her to secure her son’s release. The lawyer told her that after she sent him the money, her son would be home in two hours.

“When I refused to give him the money until after my son was returned, he postponed Ayham’s [supposed] day of release again and again. He would speak with confidence and sometimes give the phone to a third person who was apparently the officer in charge of Ayham’s case,” Hallak said. “I felt like he was scamming us, but even if there was just a one percent chance that he was telling the truth, that was enough for me make an agreement with him and start collecting money in any way I could.”

The extortion continued for some time, with the lawyer promising her son’s imminent release if she would just give more money. After the lawyer stopped contacting her, another broker stepped in with a new story.

Hallak endured this cycle of hope and disappointment, unaware that her son had been killed just four days into his detention in the Air Force Intelligence branch in Damascus.

Despite the fact that there are no means of ensuring that payments actually reach their stated recipients, sometimes the payments do achieve their intended effect. According to the families surveyed, 46 percent of payments resulted in achieving their purpose, while the remainder seemed to have been made with no apparent benefit.

The economic value of the detention trade

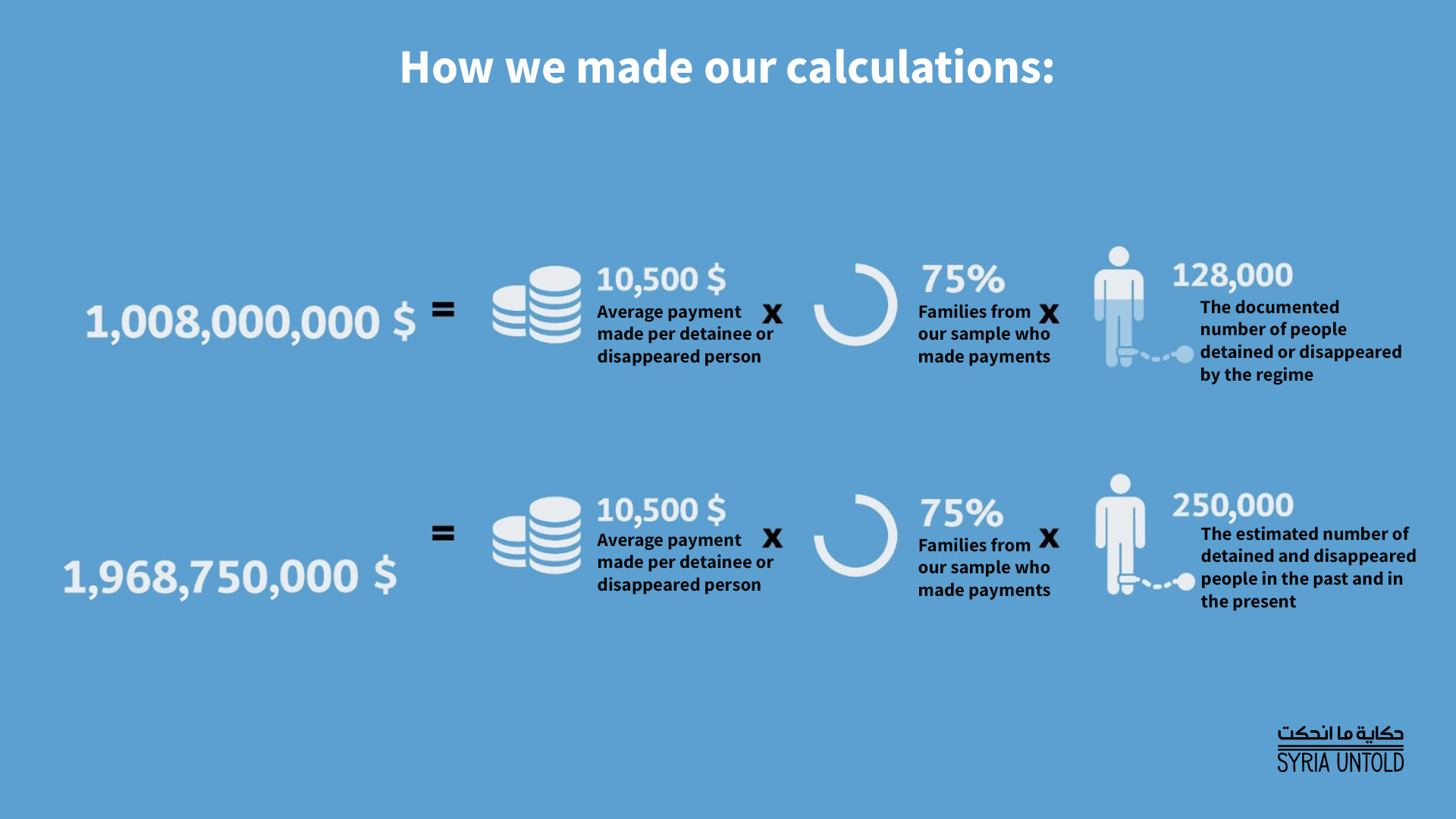

If the case sample is taken as representative of Syria as a whole, it can be used as a basis to estimate the value of the detention trade for government officials and the network of middlemen who work on its peripheries.

At the lower end of the spectrum, the value of this detention trade could be estimated at about one billion US dollars. This is based on the lists of detainees in the period between 2011-2019 documented by the Syrian Network for Human Rights (SNHR) who are still under arrest or whose whereabouts are unknown. It is important to note however, that these lists do not include those who were released from prison or were killed in detention, nor those whose names were not documented.

Hallak endured this cycle of hope and disappointment, unaware that her son had been killed just four days into his detention in the Air Force Intelligence branch in Damascus.

If all former and current detainees are included—numbering around a quarter of a million people—the total value of this trade reaches two billion US dollars. This amounts to more than two trillion Syrian pounds (at the exchange rate used when this article was originally written in April 2020)—which is about half the value of Syria’s 2020 budget. This amount is also more than quadruple the entire wages paid out to Syrian public sector employees in 2020.

The following graphic details how we reached the aforementioned calculation:

Regardless of the proportion of bribes that reach their intended destination rather than being spirited away by fat-fingered middlemen, the issue has become one of a de facto redistribution of wealth from the pockets of regime opponents to its supporters. This wealth redistribution has affected the entire fabric and cohesion of Syria’s security apparatus and the political and economic networks that have sprung up around them in recent years.

The extent and value of these financial networks become clear when compared to the salaries of many of the officials participating in these networks. Today, a Syrian judge’s salary is no more than $200, while officers in the military and security establishment make less than $100 a month, according to the exchange rate at the time of writing.

What about the families?

Sondos Falfala was arrested at a protest in Latakia in mid-2011. The 39-year-old was pregnant with her second child at the time of her arrest and gave birth while still in detention. Falfala was moved between several different security branches during her nearly year-long detention. To free Falfala, her mother paid around $45,000.

Once Falfala was out however, she did not receive the welcome she expected. “My husband refused to see me and we broke up. I left the city out of fear that I would be arrested a second time. I didn’t get to see my mother or father until their deaths. The worst thing, however, was that my two-year-old daughter did not remember me, and it was painful trying to convince her that I was her mother,” Falfala told SyriaUntold.

As part of the investigation, we spoke to young wives who had lost their husbands, parents waiting for their children’s release, and young men and women who were children when their fathers were arrested.

The psychological and social impact of losing a family member is not something that can be quantified. Every detained and disappeared person is an open wound for the family that can’t be healed until the family member returns. In one case included in this investigation, a family member said that even though their five-year old daughter has never met her father, as he was arrested before her birth, she keeps a piece of candy hidden for him, in case he should come back tomorrow.

Estimating the economic impact of this mass system of arrest and disappearance is easier, as every arrested individual leaves behind a vacant economic role. Among the 100 cases investigated, 75 were married and had families to care for and support. 65 of the cases were between 20 and 40 years old, the most economically productive ages. 45 of them had at least a university education, the product of their families’ years of investment and care in raising and educating them.

In addition to the effect that the absence of a family breadwinner has on their loved ones, the money spent by families trying to pry their relatives from the jaws of Syria’s prison system has brought about half of the surveyed cases to extreme poverty. To cope, these families have eaten up their savings, sold property and gone into debt.

Of the 100 surveyed cases, the government has released 41 of them, including those who were released on bail and those who served some time. No cases were deemed innocent. Three quarters of those released told SyriaUntold that they left Syria carrying psychological and physical wounds from their time in prison. There remain 50 other cases whose families know nothing of the fate of their detained relatives.

“For the regime, this is a trade that feeds its security and judicial institutions, and it has no problem with it,” a 40-year old detainee from Aleppo who paid $20,000 to secure his release after six years in detention, told SyriaUntold.

“If the regime released 100 people today, tomorrow they could arrest 200 more, and start the cycle all over again.”