I knew Bassel Shahadeh for many long years. I first met him in 2006 or 2007, when we were both volunteers in the Syrian Environment Association. The group did volunteer activities in schools and streets in Damascus. We worked to plant trees in other cities, too, though we mostly focused our attention on the capital. We would go together to elementary schools and work with the children or, for example, we’d do cleanup campaigns on the Barada River, plant trees in various parks, clean up the streets and hold awareness campaigns for children in public parks. We thought we were changing the world with our little acts of volunteerism.

A few years later, perhaps in 2009 or 2010, I volunteered with a group of young women and men, some of whom became my friends, in an unregistered youth campaign to educate displaced people from in eastern Syria. They had set up tents around the big cities, such as Homs, Damascus and Aleppo, after leaving homes due to the drought that struck in 2005. The government offered no real plans to solve the issues caused by the drought, despite the impacted areas being dependent on agriculture.

This was how hundreds of thousands of Syrians became displaced, living in tents they set up hurriedly near the big cities, so that they could find any sort of work for bits of bread.

We chose two camps located between Damascus and Quneitra, in an area called Rasm al-Taheen. We’d go there at least once a week to play with the children, teach arithmetic and bring them games. We also brought journalists to cover their living situation, despite the security personnel banning such coverage.

Within the margins, and breaking free: Syrian cinema

23 January 2021

Randa Baath: 'Any cultural act is vital'

12 March 2021

An intelligence vehicle would come along and question us each time we visited the camps, until they knew our names and all our answers, even before we said them.

Bassel Shahadeh was part of the aid group that would visit the two camps. If I remember correctly, he didn’t take part in the educational activities, but he did bring gifts for the children to give away holidays, or he brought clothes and other things that the people living in the tents needed.

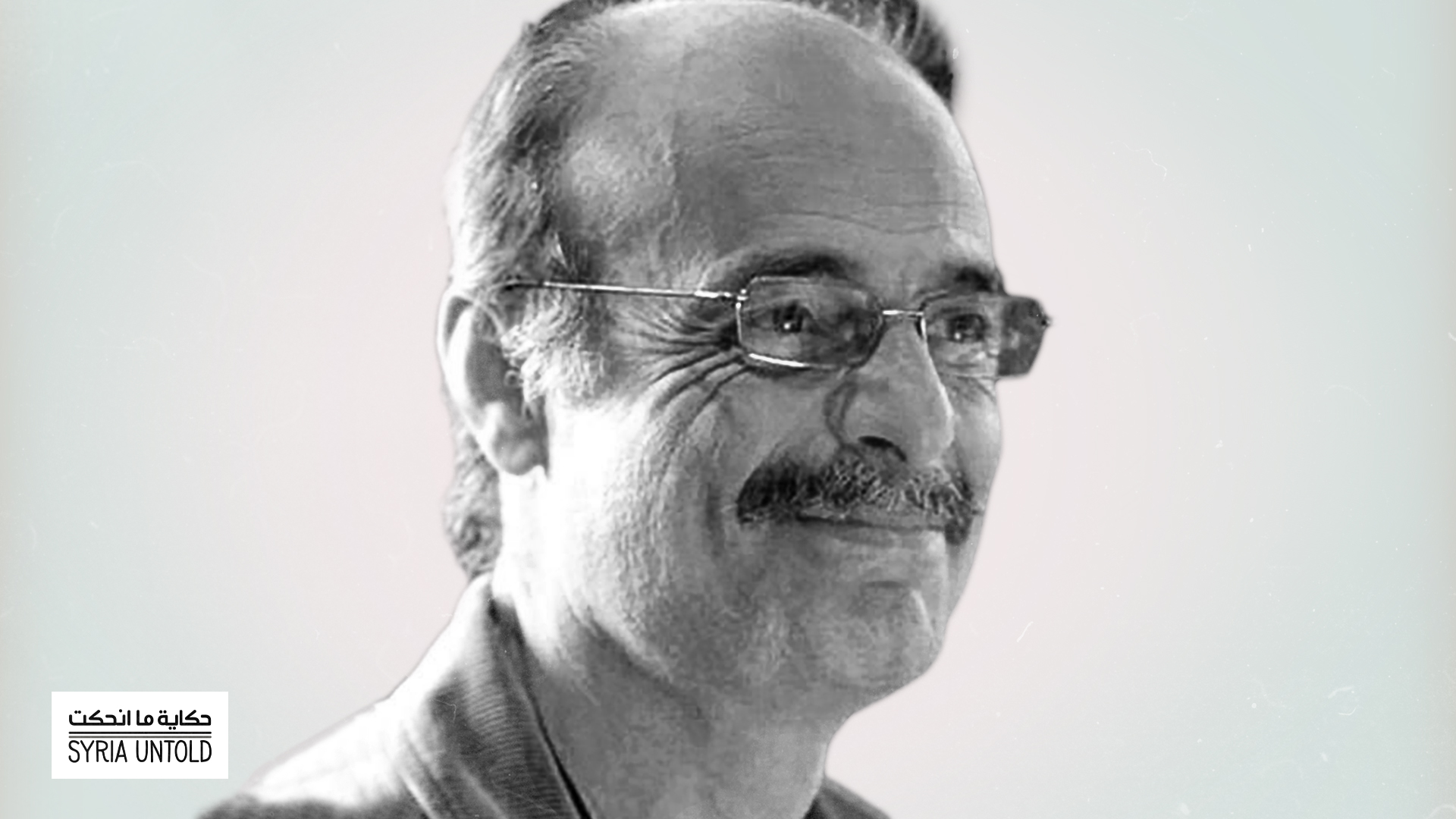

I met Bassel again during a demonstration that he had helped organize in front of the Egyptian embassy in February 2011, in support of the Egyptian revolution. This was before the Syrian revolution started. I remember him there, and I remember one of the officers whisking him away to ask him about his activities, as he was one of the organizers. Bassel was gone for about 10 minutes, then returned with a smile on his face. His face never betrayed any fear; hope was the only thing you’d see in his eyes.

We didn’t become close friends. But we shared knowledge, respect and many mutual activities and friends. We met often because of this. There was the communal garden, the Syrian Environment Association office, the displacement camps and cinemas—and here I mean specifically the al-Kindi Cinema and the Dox Box documentary film festival. We’d see each other at concerts in the Jazz Festival at the Citadel of Damascus, or in the Qishleh Park in the Old City, when a band would perform as part of a program that I remember was called “Music on the Road.” I ran into him on marches organized by the Jesuit Priest Frans van der Lugt; there is one that I remember in particular that went through Wadi al-Nasara (“Valley of the Christians” in Arabic), an area of rural Homs. I think it was 2009.

These two things will connect me to Bassel for as long as I live: the film, and the day of his murder, which coincides with my birthday.

There was another coincidence that bound Bassel and I together, albeit a sad one. Nine years ago today, on my birthday, the Assad regime bombed Homs, killing Bassel Shahadeh. This is how my birthday came to be associated with Bassel’s death, forming an unshakeable bond.

My relationship with Bassel did not end with his death.

Bassel shot a film in 2012, though his death prevented him from completing it. The film discusses the participation of Alawites in the Syrian revolution, through meetings with activists born into the sect. They speak of their experience of detainment, protest and activism against the Assad regime.

Long night to resurrection

05 February 2021

On narratives of the Syrian revolution

15 March 2021

At the end of 2012, one of my friends, who owned the materials and rights for the film, asked me to complete work on it. I contacted Bassel’s friends, family and everyone who had a relationship to the film. Then I worked to complete it, and it finally saw the light of day in 2013. The film was only shown at three exhibitions: one in Istanbul, one in New York and another in Paris. After that we stopped showing it, despite Al Arabiya having expressed willingness to air the film—we had even made an agreement and they had announced that they would air it. One of the characters of the film, who was still in Syria, alerted us that he would be in danger if we were to continue screening the film. So we stopped, and we are still unable to screen it to this day.

On the day we screened the film in the Syrian Cinema Club in Paris, the house was nearly full. Before we started the film, one of Bassel’s friends gave a few words of introduction. He was unable to say anything about Bassel in my presence, he told us, because here I was carrying Bassel’s legacy with this film. These words weighed on me. Who am I to carry someone’s legacy, especially if this person is Bassel Shahadeh, an icon of the Syrian revolution?

Bassel’s family and friends handed me a great responsibility when they asked me to complete his film, a responsibility that will continue to stay with me, like a mountain on my shoulders. It will sit there until the end of my own life.

These two things will connect me to Bassel for as long as I live: the film, and the day of his murder, which coincides with my birthday. But what connects me to him even more is a deep belief in freedom, in art, human dignity and justice, and in a faith that cannot be lost.