Read this article in its original Arabic here.

It was April 2021, and the Syrian Civil Defense had launched a project to remove the rubble of collapsed buildings. This was in opposition-controlled areas in northern Syria, including on some sites that the Islamic State (IS) had once used as camps, security headquarters and prisons.

One of the condemned buildings was known during IS control of the area as the "Islamic Court Prison of the City of al-Bab." IS imprisoned me there for several months in 2014 before I managed to escape.

When the Civil Defense volunteers informed me they were going to remove the rubble from that prison, I decided to go along with them. I hoped to find something about the former prisoners, names that had long been forgotten after IS lost control over northern Aleppo governorate and, eventually, suffered geographical defeat.

Though IS is no longer present in al-Bab, family members of many of the people who went missing there still await any news of their loved ones, who had been arrested and forcibly disappeared by IS. In March 2019, the Syrian Network for Human Rights, a UK-based monitoring organization, counted more than 8,143 people arrested by IS whose fates remain unknown. The majority of the missing are men, though women, including local activists, have also disappeared.

Among the thousands of missing persons, some had been imprisoned at the Islamic Court in the city of al-Bab.

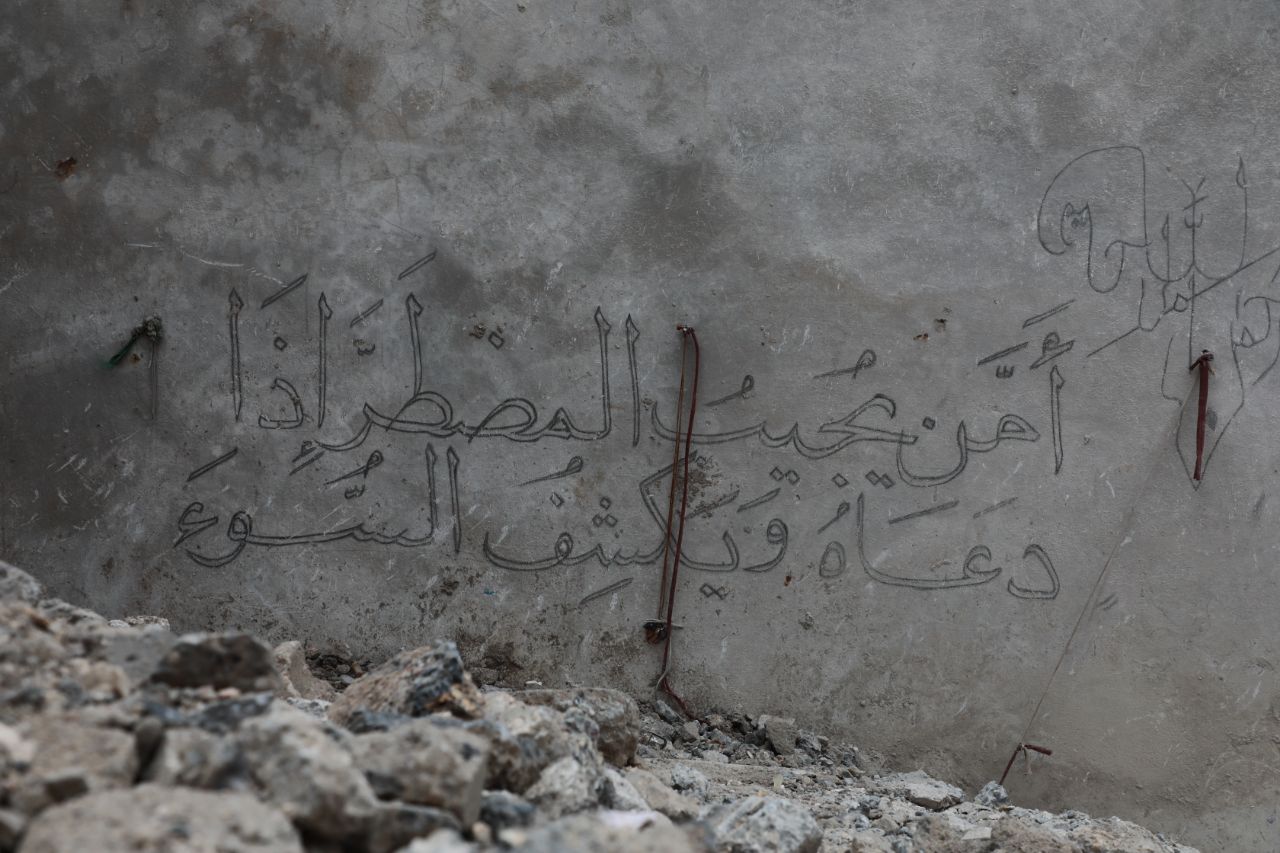

He painted the Quranic verse that says: “Who responds to the distressed when they cry to Him?”

I decided to accompany the Civil Defense and document the names—if any—that remained scrawled across the walls of the building’s prison cells before they were removed forever. I’d resurface my own memory, as well as the testimonies of detainees who had survived this prison and who knew the location of dormitories, interrogation rooms and torture chambers.

At first, the volunteers who came to remove the rubble thought I wouldn’t find anything, as it had been years since the building had been destroyed in Operation Euphrates Shield, a military campaign that saw Turkish-backed opposition forces seize control of the area. But for reasons that escaped me, I had the urge to remain on site until the debris had been completely removed.

I toured the place and looked around for several days, watching the excavators. I didn’t miss a single blow dealt by these heavy machines to the prison’s body. Finally, on the fifth day, and after the machines removed dirt and stones that had been compacted between the dormitories, some writing began to appear, such as the numbering of dormitories and the names of the interrogation rooms.

I climbed down between the former prison cells, carrying my camera and my keffiyeh.

In prison, again

I took pictures of everything that was written on these walls: warnings from the prison guards, the phrases written in bold black letters inside the interrogation rooms, and, after wiping the walls with my keffiyeh, other phrases and names that began to appear in scripts of various sizes.

Here was a memento of Walid al-Sheikh from the city of al-Bab, whose fate is still unknown, and there was a memento of Rabia al-Ali from the city of Qabasin, who was executed on charges of belonging to the Kurdish Islamic Front. And so, my camera documented more than 120 names, written haphazardly on the walls of the dormitories. Some of the detainees had written their phone numbers, hoping someone might find them and contact their families.

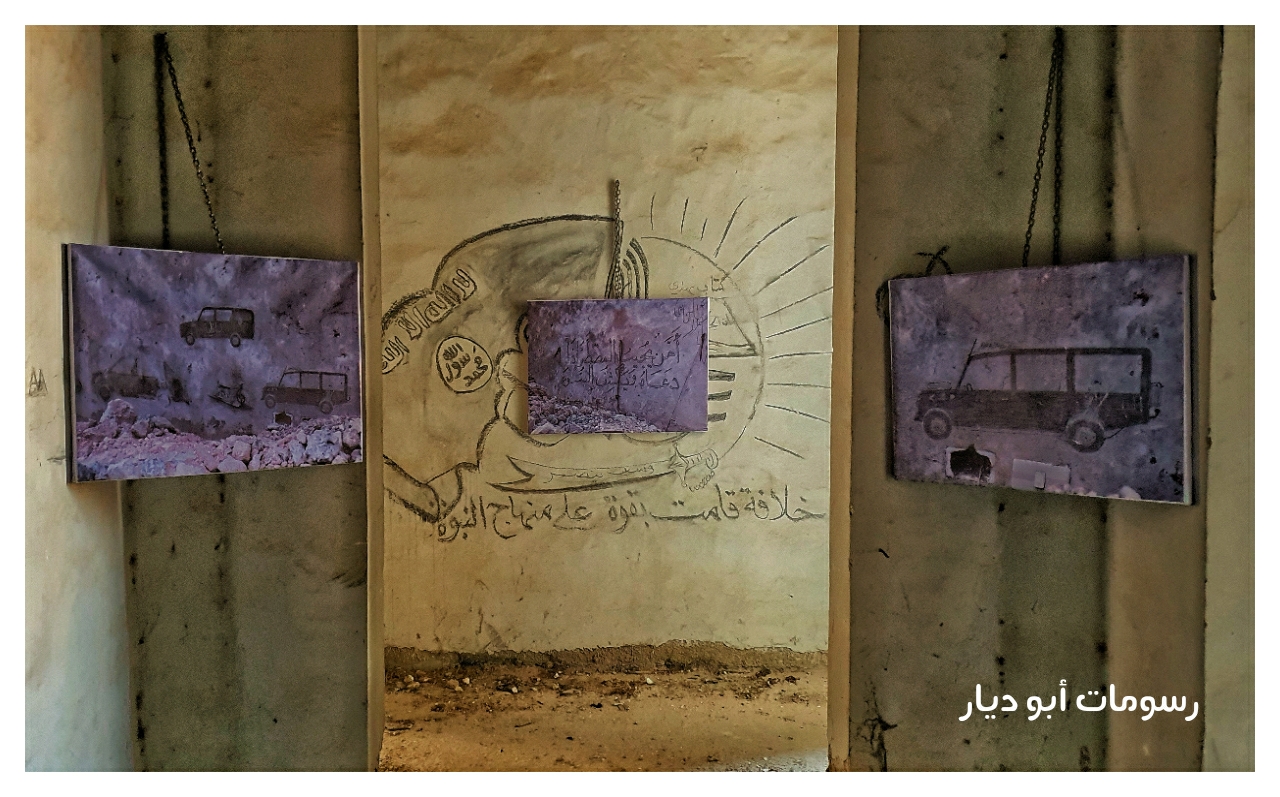

Among all the memories traced by the hands of detainees and jailers alike, I found drawings in cell number four, on the second underground floor of the prison. This was the cell that housed all the prisoners arrested for trying to escape on March 5, 2015. I wiped the dust off my camera’s lens and the walls of the dormitories and continued to dig out these drawings. Some of them belonged to a man named Abu Diyar, and it seemed to me that they were historical manuscripts being uncovered at an archaeological site. That is exactly what they were.

Abu Diyar

Abu Diyar was a Kurdish detainee hailing from Mashtal Nur in the city of Kobani, east of Aleppo.

He was 31 years old and working as a well-digger in Lebanon when IS launched its attack on Kobani in September 2014. Abu Diyar lost contact with his family. He found no other means to make sure they were safe but to leave his work in Lebanon and travel back to Kobani in the hope of finding them. When he reached an IS checkpoint in the city of Manbij, east of Aleppo, he was arrested due to the city of origin listed on his ID card.

Abu Diyar was unable to read and write, neither in Kurdish nor in Arabic, and he was not proficient in spoken Arabic. He was always silent when we shared cell number four together, because speaking a language other than Arabic was forbidden inside the prison. The fate of anyone speaking another language was death. We learned that when one of the guards, Abu Omar al-Halabi, threatened the detainees.

Abu Diyar and other Kurds spoke little, except for when it was necessary. I would find them whispering or teaching each other some Kurdish letters. Abu Diyar was also learning Kurdish letters. I could hear some of them whispering to God in Kurdish as they knelt in prayer.

The drawings on the wall

In cell number four, there was no source of ventilation, and no sunlight. The cell was dimly lit by an LED with a weak battery. It was very humid.

Some of the cell's detainees were released during prisoner exchanges with the various warring factions. About 80 detainees remained, including 20 Kurds whose names were not included in the exchange lists provided by the majority-Kurdish People's Protection Units (YPG).

Kurdish detainees repeatedly asked the guard about their fate. After the departure of the last fighter belonging to the party ("party fighter" was the name given to anyone who fought in the YPG) as part of the prisoner exchanges, despair descended on the detainees, and on Abu Diyar. He spent the rest of his time drawing on the wall after having fixed a thread from some worn-out clothes that he used as a ruler. He painted the Quranic verse that says: “Who responds to the distressed when they cry to Him?”

Abu Diyar was not fluent in Arabic, rather painting these verses by shape. His paintings extended to all the walls of the cell. There were Quranic verses and architectural drawings like a mosque and a palace, painted as if by an expert. He turned the walls of the cell into a permanent exhibition, drawing his pictures with a black pen under dim light. Abu Diyar’s constant painting was only interrupted by prayer.

On one of the walls, Abu Diyar painted a motorbike. Perhaps, like many village youths, he had the ambition to own a motorbike before his death. Maybe he rode his illustrated bike in his mind. And because dreams have no limits, he drew himself a large car to drive and a large house to live in, all in his imagination.

He responded to his jailer in the same language with which he fought people. He wrote a Quranic verse that says: “We sent thee not, but as a Mercy for all creatures.” He painted this verse on the wall opposite the cell door so the guard could see it every time he entered.

Abu Diyar painted over 18 verses and illustrations of various sizes.

A fate unknown

I collected his 18 drawings, all painted in just one of the prison cells between which he moved, after having been transferred between several prisons in Raqqa, Manbij and al-Bab. I collected these drawings of his from that cell in the former Islamic Court prison in al-Bab, and later held an exhibition in the granary of that same city. IS had also used the granary as a headquarters, where it made explosive booby-traps and set up a prison. I told people about the difficulty of drawing in that cell; that cell in which Abu Diyar lived.

I spoke to those who attended the exhibition about the accuracy of his hands, his ability to adjust letters and measurements, and the hardship of drawing in such a place. I asked them to take a closer look at the precision of his lines in a place where our bodies trembled in fear every time the cell door was opened. I held this exhibition in honor of the spirit of Abu Diyar and the souls of all the ones who went missing in all prisons.

The prison guard and his companions scattered, ending up in prisons, underground or dead, and their “state” disappeared geographically. Abu Diyar’s art remained.

After IS refused to release the remaining Kurdish detainees in its prisons—those who were not recognized by any prisoner exchange list—many detainees were executed. Among them was Haji Issa, our companion in cell number four who appeared along with a number of Kurdish detainees in a video clip issued by one of IS’ media offices

Abu Diyar’s fate remains unknown.