This article is part of a limited series marking a decade since the start of the Syrian revolution. Read this piece, originally written in Arabic, here.

It has been a decade since the outbreak of the Syrian revolution, the divergence of its paths and the onset of the Arab Spring.

There is no better time than the present to recall that event and tackle it from different angles. We can recall the moment of hope that accompanied these revolutions, or focus on what the uprisings represented when they cracked open the public sphere that had been forcibly closed for decades by different Arab despotic regimes.

We can also highlight the Arabs’ real appearance, for the first time, as an active human entity seeking to control its fate and affairs. Or, we can focus on the defeats, downfalls and humiliations that accompanied the uprisings, and the constituted reasons lying beneath their tragic outcomes.

The different angles to tackle this event are not always conflicting. In fact, they might complement each other and present a more diverse and multipronged image of the Syrian revolution and Arab Spring. There isn’t one way to understand the Syrian revolution or a single moment that is sufficient to grasp it, even though the current text starts from the moment of defeat and humiliation, in an attempt to look at the path of the uprising throughout a whole decade.

On narratives of the Syrian revolution

15 March 2021

Questions about growing change in Syrian narratives

12 January 2021

Taking the defeat and confusion surrounding the revolution as a starting point, we must first distinguish between the just cause of the oppressed rebels and their own perception of justice, which might have been the reason for stronger (or no less serious) injustices than those they revolted against. I believe this difficult distinction and the pressing need for it in the Syrian context constitute the root of Syrian confusion.

A state of confusion ensuing the revolution

The Syrian revolution sparked deep confusion among several social groups and leftist and nationalist political currents, both in Syria and the Arab world. Many times, these concerns turned into clear resentment, and at other times, they just took a generally negative stance towards the revolution. Opposition to the revolution did not necessarily entail alignment with the regime, but was perhaps equally negative towards the regime.

Stances towards the revolution were not clear-cut as to whether they were with or against it, as the rebels and regime tried to demonstrate. Of course, not much helped those stances, at the time and even now, to persist or materialize into serious options, because of the gravity of the conflict and its polarization. Perhaps the more important point was that neutrality towards the killer and the victim, the strong and the weak, was far from neutral in the end.

To a large extent, one can explain many people’s apathy to the uprising with their high ideological standards, be they leftist or nationalistic, and with their exclusively ideological perspective of the world and the conflicts it dictates.

For instance, to take a stand on any conflict, one must decide their position from the central conflict with US imperialism. This way, local conflicts would be emptied of their personal content, and alignment with the worst dictatorships could be justified based on their contradiction to imperialism.

The Syrian revolution was indeed confusing, as were other Arab revolutions, as it appeared later on. However, the Syrian confusion was much deeper, more pronounced and costlier in the end.

But taking the “ideological high ground” did not work in one direction only—against the rebels. In fact, it was in their favor sometimes. Several groups and currents sided with the Syrian revolution because the rebels were Sunni Muslims fighting the Alawite regime. Facing the negative ideologization from leftists and nationalists, there was a positive ideologization from Islamists. Nevertheless, this ideologization remained limited to a relatively small crowd, and it cannot explain the generally confusing stance towards the revolution among the wider crowd that went beyond ardent ideologists.

In turn, this dual ideologization is responsible for a significant part of the confusion of the Syrian revolution. Was the ideologization part of the revolution’s ideology itself, which would explain the distance that leftists and nationalists took from the revolution (being an Islamist revolution), as opposed to the Islamist identification with it? It is difficult to give a direct and honest answer because one can find all the answers in the revolutionary statements during the first years, from the nationalist ones to the Islamist ones [i].

The confusion behind the Syrian revolution, after years of civil war and strife, and in the wake of the rise of the Islamist jihad, constitutes a good starting point to reconsider what happened. The Syrian revolution was indeed confusing, as were other Arab revolutions, as it appeared later on.

However, the Syrian confusion was much deeper, more pronounced and costlier in the end. The confusion here is not related to the dispute over tarnishing the image of the revolution, or a pathway to shield it from accusations or to condemn a bloc for its stance towards that revolution. All these issues are actually behind us now. Confusion now serves as an indication of the reality of the Syrian quandary and what we can learn from it.

A revolution for freedom and social insurgency

The beginnings of the Syrian protests were marked by a wide and diverse presence, but they did not reflect the actual level of Syrian diversity. Minority groups were present in the squares, even though their participation was limited and symbolic. The Syrian nationalist and democratic opposition with its general frameworks was also present, and it later split into two rivaling groups, divided over matters of armament and intervention. The first group, including the Syrian National Council and the National Coalition for Syrian Revolutionary and Opposition Forces, continued with the political institutions of the revolution, while the other, which included the National Coordination Committee, did not participate in these institutions.

A famine, a ship and a folk song that spanned borders

18 December 2020

Songs of nostalgia in New York City’s long-lost ‘Little Syria’

05 March 2021

During that phase, the broad revolutionary discourse focused on general values: freedom, dignity and the unity of the Syrian people. This discourse considered the Syrian uprising one of the waves of the Arab Spring, which was seen as a conflict with the authoritarian regimes (struggle for democracy), a youth insurgency (generational transformations in response to a deep-seated economic crisis affecting the youth) and a social conflict (between the countryside, cities and marginalized neighborhoods, affected by the shift towards openness and by market policies).

The self-image of the revolution resembled, to a large extent, the image of democratic revolutions during the decades preceding the Arab Spring, from Latin America to the collapse of real socialist regimes in Eastern Europe.

However, we must not miss a key point, which is that this image reflects the people who spoke out and had the possibility of talking to the media; the people who knew the right way to formulate their demands to meet the expectations of the supporters of the transition and the revolution (certainly many of them were convinced of these demands).

This discourse was in itself among the first sources of confusion. It totally hooked us, and we believed it. The discourse was not deceptive, at least not the whole time. We were born into a society which taught its people for years not to say what they think, and to simply say what was allowed. Therefore, society had to use a general, accepted language to express itself, which subsequently indicated the existence of an implicit, undeclared meaning.

It was forbidden to talk openly about sects in Syria—that is, unless it involved the image of a priest hugging a sheikh under the Syrian flag. Any signs of sects were eliminated from the public sphere.

The names of various areas were changed accordingly—from the Territory of the Alawites (Jibal al-Alawiyin) to Latakia Mountains (Jibal al-Lazikiya); from the Mountain of the Druze (Jabal al-Druze) to the Mountain of Arabs (Jabal al-Arab); and from the Valley of the Christians (Wadi al-Nasara) to Wadi al-Nadara, and so on.

But sectarianism and its expressions remained strongly present in the way of life, in the government’s relations and even in language, albeit not openly.

Islamist revolution and sectarian conflict

The Baath regime in Syria was not only authoritarian, but also corporatist. It ensured the participation of groups in state professions and economic jobs. Representatives of these groups played the role of mediators between the state and its people in several of their affairs, in exchange for their loyalty and obedience to the state.

However, this participation did not imply participation in power. Unions represented professions and the demands of workers and peasants, and relayed these demands to the state. They earned the right to participate in determining the economic policy and reaping privileges and economic advantages for their members.

In exchange for this, the unions professed the loyalty and submission of their members to the state and guaranteed the deterrence of any attempts to revolt against the government from their members (all this happened before the increasing weakness of the role of the unions since the 1980s, with the adoption of a new economic policy). By the same token, Muslims, Christians and other groups were also represented and able to participate. The role of Christian and Muslim clerics surfaced at that moment.

The transformation of the Syrian conflict into proxy wars and regional settlements added more confusion to the Syrian revolution. It was no longer possible to see any victory as a purely Syrian one, but merely a winning score in a regional conflict.

The regime tapped into its participatory reasoning to deal with the long-standing sectarian issue in the East. Dealing with sects—especially the publicly recognized ones—happened through the mediation of their legitimate representatives (the clerics) within a controlled logic of distribution of power and authority among them. Of course, this process occurred within a previously controlled discourse of Arab nationalism and Syrian patriotism. With rising sectarianism, which the regime played a key role in, and the weakness of other affiliations and their marginalization, and amid the new economic policies (unions and social identities which the Baath adopted during its populist era), sectarian identity became more pronounced in public life and was essential to reaching state positions and securing privileges.

Other various forms of civil identities re-appeared alongside the rise of sectarianism. Tribalism was revived in recent decades (tribal sheikhs in the People’s Assembly), and it became easier for people to refer to the sheikh of their tribe (who had been forgotten for decades) instead of referring to the union to secure a job or lodge a complaint.

Due to these transformations, people’s reliance on civil identities in their relations with each other or with the state increased and extended to the Syrian revolution [ii]. Would the Syrian revolution establish a new Syrian national identity, or would it turn into Sunni insurgency and rebellion based on Sunni chauvinism both feeding into it and expressing its oppression and injustice?

In pictures: Under olive trees, volunteers teach displaced Idlib children

28 December 2020

The body, between event and memory

25 January 2021

Still, not all Sunnis supported the insurgency, and many of them—especially city dwellers—were vocal about their disagreement. The matter was settled early for various reasons, including the regime’s rising suppression of the revolution, the premature and rapid elimination of groups that adopted a national discourse, as well as the role of Gulf money in the general Islamization of the opposing factions.

The regime and its Islamist enemies all participated in this oppression. The Syrian revolution increasingly took on the image of a Sunni insurgency, which was clear from the symbols and connotations linked to that identity (the names of factions from the beginning), and it sought to mobilize people by invoking this identity. Despite the rural nature of the Syrian revolution and its marginalized cities, it did not focus on the aspect of being the revolution of farmers and the cities’ poor.

Facing the revolution’s transformation into the image of a Sunni insurgency, the regime maintained its anti-sectarian national rhetoric and preserved the image of the state: a state for all its citizens. While it was no longer possible for Syria’s minorities to remain in opposition dominated areas due to the looming risk of death (for Alawites and Yazidis who experienced this fully) or the dire and humiliating circumstances (for Christians and Druzes), the regime upheld a national image in the areas under its control. The cost of Sunnization of the revolution was not limited to breeding a dispute with sectarian minorities, as Kurds also joined the frontlines with the revolution.

At some level, the Syrian revolution was a sectarian war, and this was not a unique event in the Syrian context. Popular insurgencies against the Baathist regime in Syria, beginning with the first insurgency in Hama in 1964 to the Islamist insurgency from the end of the 1970s until the attack on Hama in 1982, and reaching the Syrian revolution, were Islamist insurgencies in the framework of a sectarian feud. Meanwhile, the popular scope of the leftist and democratic protests, whether through communist action or the Syrian Communist Party – Political Bureau, remained limited.

The trade union strikes in the early 1980s and later on, the human rights and civil society movements, the intelligentsia’s petitions in the 1990s and during the early years of Bashar al-Assad’s rule, and finally the civil society coordination committees during the first years of the revolution, were also limited in scope.

The Sunni aspect of the Syrian revolution advanced mobilization and recruitment, and gave the protests religious meaning and values that encouraged martyrdom and confrontation after the collapse of the mobilization potential of leftist and nationalist ideologies. Still, this aspect limited the scope of the Syrian revolution both at home and abroad.

Proxy wars

Although the rural nature of the Syrian revolution did not play a significant role in portraying this movement as a social insurgency for justice and equality, it nevertheless carried many characteristics of peasants’ revolts, notably at the military level. The factions were scattered, and they were positioned in local bases and founded on group solidarity that did not go beyond their regions.

The easy Gulf money that rained down upon factions only added insult to injury; turning the leaders of factions into warlords. Not much information is available about the economic management of the factions during the Syrian war, but a general idea can be deduced now (though it needs to be supported with sufficient field studies).

Perhaps it is better to view Sarout’s whole path as an ambiguous one, rife with different possibilities; some of which were achieved while others faltered.

Given the abundance of money, none of the factions demanded the regulation of the local economic cycle in the areas under their control. Their financial and economic capacities, primarily thanks to Gulf money, were unconstrained by the capacities of the localities where they were positioned.

Consequently, the inhabitants of these areas did not have much sway in their negotiations with these factions. To get the money, the factions had to fulfill the demands of the funding party—they were weak facing the funder and strong facing the locals. They also had to appear stronger than other factions to ensure a better position and attract funding and support. This explains the multiple and serious conflicts between factions to control checkpoints, not to mention the economic role of these checkpoints that collected illegal levies, known as khuwa. Deprivation from foreign funding—that depended on political choices—threatened the survival of a certain faction and its ability to ensure arms or pay the salaries of its fighters [iii].

This situation was not limited to the military factions alone, as the same could be said about the Syrian regime, which persisted economically thanks to Iranian aid. Consequently, the regime no longer relied on the potential of the Syrian economy alone. The civil war actually exceeded the economic capacity of Syrian society, in general, thus weakening it and making the Syrian war a foreign matter devoid of local decision making power. The regime was no longer living off its citizens’ capacities, and its relationship with them turned to one of illegal levies and sustenance.

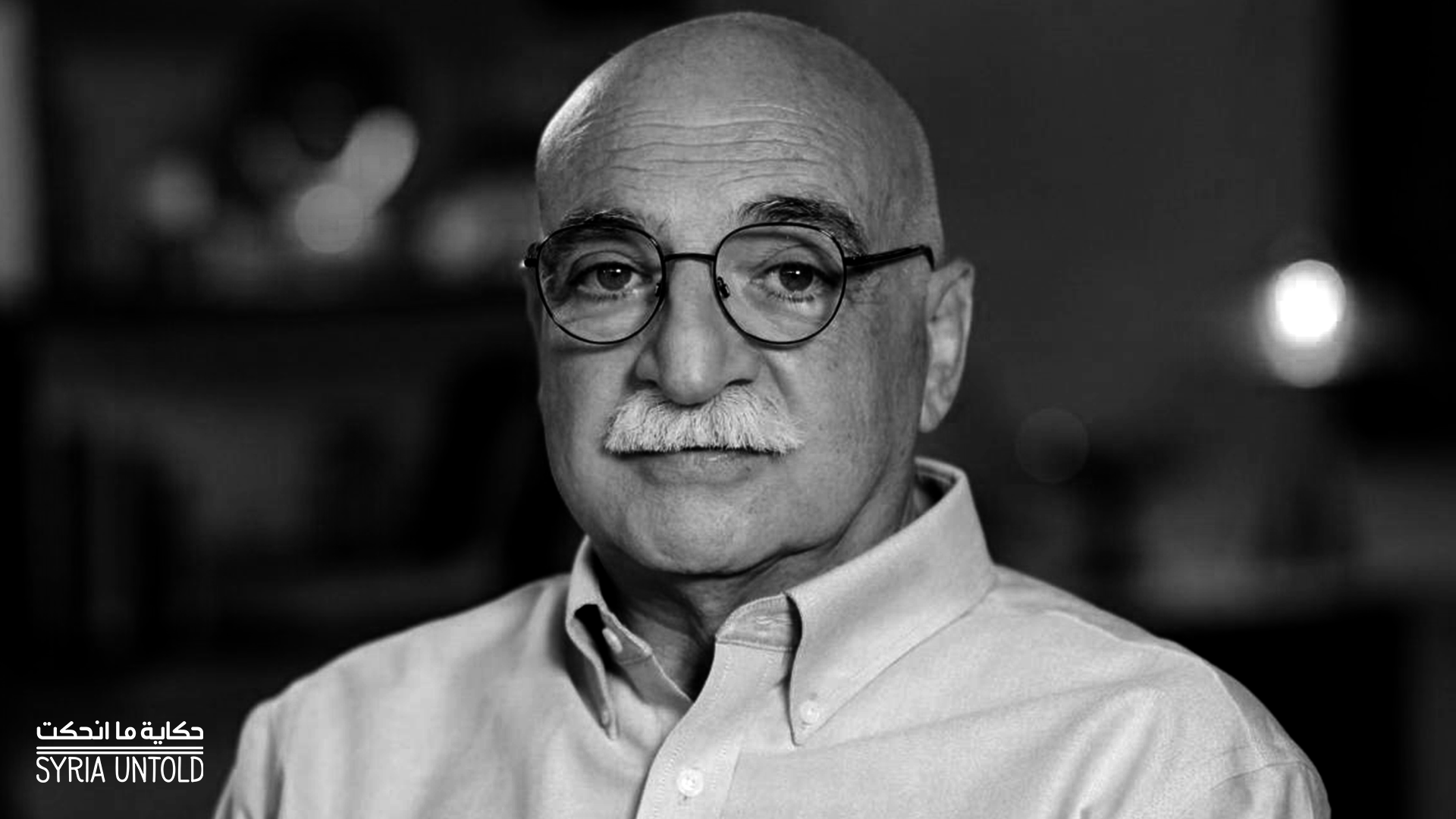

Mourning Hassan Abbas

10 March 2021

What did exile change in our narratives?

26 January 2021

This foreign dimension turned Syria’s civil war into a proxy war in which Syrians had little say, when it came to ending the conflict and determining its fate [iv]. Consequently, Syrian fighters easily became warlords and mercenaries, whether for Turks, Russians or Iranians.

The transformation of the Syrian conflict into proxy wars and regional settlements added more confusion to the Syrian revolution. It was no longer possible to see any victory as a purely Syrian one, but merely a winning score in a regional conflict. This added value entrenched the confusion, in light of the alignments and groups that intervened in the course of victory of the Syrian revolution and its factions; from Turkey to the UAE, Saudi Arabia and Qatar. Many had all the more reason to be sceptical, like Kurds vis-a-vis Turkey, Palestinians vis-a-vis the UAE, Lebanon vis-a-vis Saudi Arabia and leftist and nationalist blocs vis-a-vis the Gulf axis in general.

Sarout: Image of the Syrian revolution

Abdul Baset al-Sarout can be seen as a true expression of the Syrian revolution and its ambiguity, as a popular hero expressing—to a large extent—the revolution’s crowd and reflecting its changes and transformations through his path, fluctuating stances, songs and slogans.

Sarout emerged as a popular model of revolt against injustice and a hero transcending civil divisions. He defined himself as an opponent of the regime’s injustice, without giving any positive insight on his demands. He raised issues that seem abstract and distant now, such as citizenship, the form of the desired republic, and others.

This negative form of revolt against injustice was coupled with projection on a national and humanitarian situation. He sang patriotic and folkloric songs with Fadwa Suleiman (of Alawite origins) and protested against the regime. With the Islamization of the revolution, Sarout had a change of heart and shifted to Islamist or sectarian inclinations. He thus began singing against the Alawites and threatening them. His activism turned into a sectarian confrontation (at that moment, people like Suleiman no longer had a place in the tunnels of the revolution). Later, Sarout pledged allegiance to IS when the latter emerged as the most prominent force in fighting the regime. Sarout later retracted his pledge, but he did not really seem to take back his Islamist or sectarian inclinations.

Sarout’s path stirs more confusion than rigid ideological stances. Certainly, whoever wishes to can consider Sarout’s pledge of allegiance to IS and his sectarian slogans an expression of his “real” being.

Conversely, others might believe the real Sarout was the one who appeared during the early stages of the revolution and might consider the sectarianism and allegiance to IS mere blunders or compulsory deviations dictated by circumstances, but do not tarnish Sarout’s good nature.

What I would like to point out is that perhaps it is better not to consider a certain moment a “real” one, as opposed to other “false” moments. Perhaps it is better to view Sarout’s whole path as an ambiguous one, rife with different possibilities; some of which were achieved while others faltered. Some possibilities triumphed at some point and failed at others. Given that it was a path paved with possibilities, it is pointless to ignore these possibilities or justify them in a circumstantial manner. Every possibility—especially those which were achieved—is a real one that must be fully taken into account when examining his path.

Sarout’s path, as a collection of ambiguous possibilities, is that of the Syrian revolution, whereby some possibilities cannot be overlooked and excluded under the pretext that they were not a true expression of the revolution. Everything that happened was a true expression of this revolution; from its embryonic patriotism, to its sectarian strife, anti-patriotic Islamism and human yearning for freedom. Recounting the Syrian revolution and holding it accountable in a way that would allow us to ask “what is to be done?” must be based on re-questioning it as a revolution having ambiguous possibilities.

Notes

[i] Refer to Ibrahim Hamami’s book Alawite State- Al-Assad’s Last Option, 2012, Strategic Fiker Center for Studies, London. The book reflects an Islamist position and encompasses many statements and stances of military and political leaders in the Syrian revolution’s military and political committees at the time. The statements present a sectarian outlook on the conflict (of course from an angle showing that sectarianism is a characteristic of minorities). But, the book provides a useful model that serves as documentation of the perception of a main party to the conflict and of its nature.

[ii] Refer to Mohammad Hassan’s article "IS and Tribes in Deir ez-Zor – Insurgency and Containment“, in which he outlines the tribal divisions that accompanied the dispute between IS and Jabhat al-Nusra. https://www.aljumhuriya.net/ar/37621

[iii] The Ahrar Souria faction’s experience constitutes an example of the limited capacities of a faction, no matter how strong it is, when faced with the dilemma of funding cuts. Refer to the following paper prepared by Al-Jumhuriya website about factions in Aleppo, including Ahrar Souria. https://www.aljumhuriya.net/ar/37621

[iv] Refer to the work of Ali Kadri, a late espouser of the Dependency School. He looked at the Syrian revolution from an imperialist, capitalist angle and considered it a capitalism of wars, disasters and proxy wars. Imperialism with Reference to Syria, Ali Kadri, Springer, 2019.