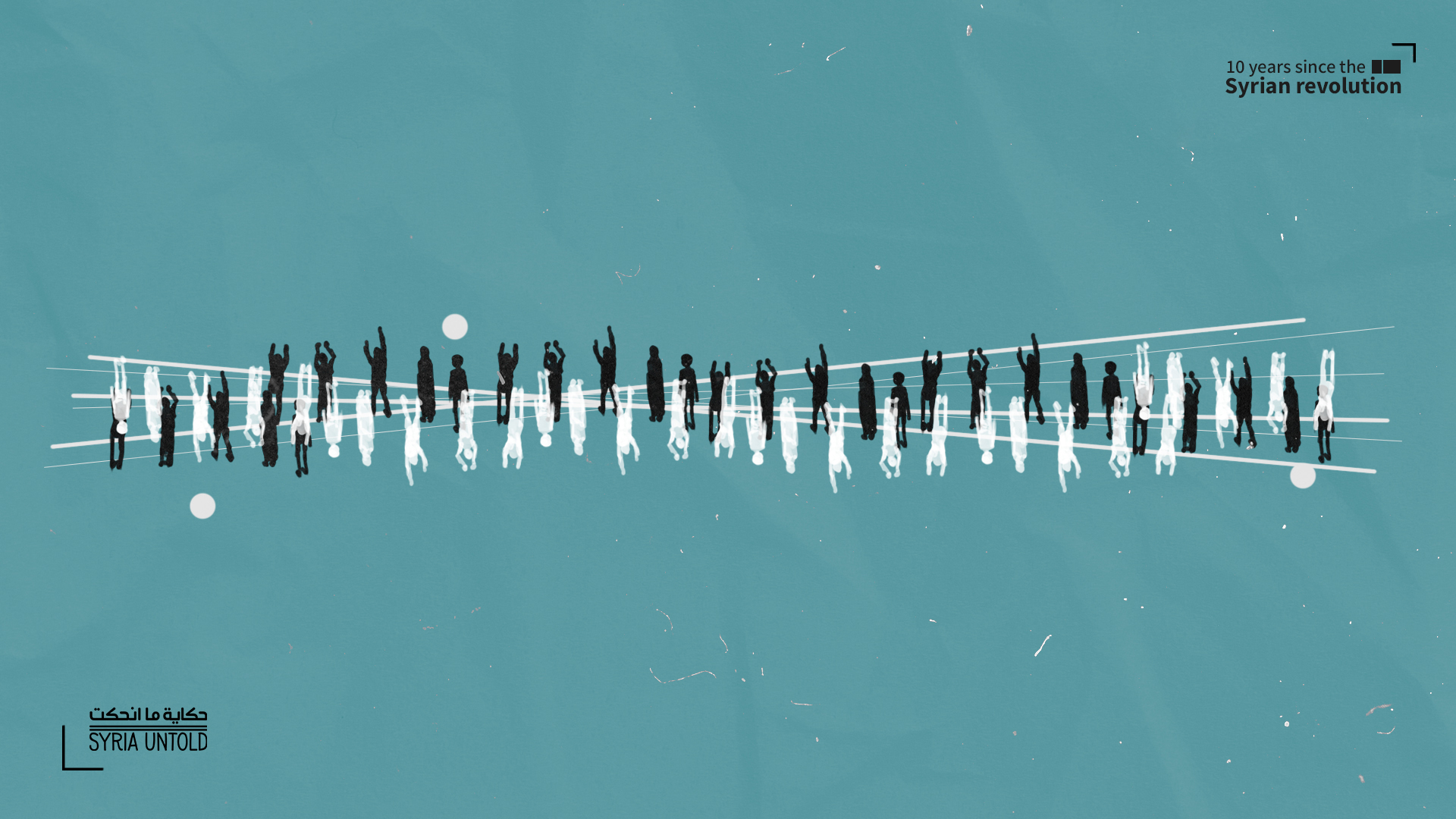

This article is part of a limited series marking a decade since the start of the Syrian revolution. Read this piece, originally written in Arabic, here.

I borrow the words of Moroccan researcher Dr. Said Bengrad when I say: "Between the word and the image, there are multiple answers and the window of possibility" [i].

I follow his approach in attempting to answer some main questions, including: what happened in Syria 10 years ago? Syrians from different positions and walks of life give specific answers to this question. The first answer is that what happened is a Syrian earthquake. It is a historic turn that changed the destinies of millions of Syrians across dozens of cities. The second answer is that what happened was a struggle between two camps: the regime and another actor. Yet, who is the other actor? This is when the answers multiply. Syrians agree that the regime is a camp in this war, and that its existence was targeted by another camp.

Answers differ when it comes to determining the identity of the other actor fighting the regime. Who are they? What do they want? Why are they targeting the regime? Was targeting the regime the plan from the start?

Here, we will examine answers describing or categorizing the other actor fighting the regime. We will do that by zeroing in on other circumstances. There were circumstances that had their toll from the beginning. However, there were others that appeared at a later stage. Those circumstances complicated the Syrian issue and its solutions, and they were embodied either in regional and international interventions or in the entry of Islamic fundamentalist groups to Syria. The questions to which we seek answers: Who is the other actor in this war? Which Syrians clashed with the regime?

On narratives of the Syrian revolution

15 March 2021

Syrian revolution and the conflict over narratives

19 March 2021

The newness and continuity of the event would put into question the objectivity of any narrative or study attempting to determine what happened a decade ago. Open wounds and great pain could blind the capacity of any actor to be objective.

What would we do if this step was premature? How could we approach what happened on the 10th anniversary of the event?

The problem is that we really need to carry out this analysis. We are not detached academics studying some historical event. We are a people in pain and our beautiful country, Syria, must be reclaimed and rebuilt. We cannot wait for the course of time alone.

For this reason, we must constantly research to be able to approach what happened from a perspective that would allow us to objectively assess the situation. It is essential to do so, for our recovery as a Syrian people. Such an assessment could equally be the basis of sustainable internal peace in Syria. Sustainability cannot be fortified except through a repeatedly corrective process that the Syrian people will go through with the passage of time. Yet, this long process cannot be achieved if freedom of expression, at least, is not guaranteed.

Freedom of expression guarantees the space to freely and fully discuss narratives. Indeed, there is a factor other than time obstructing this possibility. Let us ask ourselves, for example: Is it time, 40 years later, to analyze the different narratives surrounding the Hama massacre? I do not think so. The persistence of the same balance of power, authority, and hegemony since that event pushes the narrative to obscurity and resistance to knowledge or formulation. I am even claiming that the time to reveal what has been happening in Syria from 1963 until today has not yet come, so why are we concerned about what happened only 10 years ago? However, there is no harm in trying.

Who are the Syrians on the other end of the conflict? On the multiplicity of answers

First answer: What happened was the revolution of the Syrian people against a regime of tyranny, oppression, and looting. People were demanding freedom. The main driver of the revolution was the class of young Syrians who wanted better horizons instead of closed doors. All the people involved in the revolution, irrespective of their ideology, region or sect, support this explanation.

Second answer: What happened was a conspiracy, and the other actor was a group of infiltrators and operatives implementing a foreign agenda on Syria. This is the first answer given by the Syrian regime because the regime does not imagine Syria existing without it. Syria has belonged to Assad for 50 years. This narrative was quickly launched to face protesters.

We are not detached academics studying some historical event. We are a people in pain and our beautiful country, Syria, must be reclaimed and rebuilt. We cannot wait for the course of time alone.

The goals of this “conspiracy” differed among the other actors who adopted this narrative. Some, especially the left, gave economic justifications, such as foreign states fighting to take over Syria's wealth, especially the newly uncovered natural gas. Geopolitical justifications brought up the location of Syria as a passage from the European Union to the Arab world. This justification also attributed the war to an Israeli conspiracy aiming to sabotage the resistance axis. It was mostly adopted by Palestinians, Arabs and leftist Europeans. In fact, Hezbollah recited this discourse to us over and over again.

Third answer: The Sunni sect wants the Alawite system to fall in order to establish a religious alternative state. This answer was not only strongly adopted by the regime from the start, but also among members of the revolution and opposition to the system a year after the revolution first began.

When the regime combined answers two and three, it was highly influential, especially since starting a conspiracy theory requires local tools. With this combination, the identities of those local agents were determined in the hope of attracting sympathy—or at least neutrality—from those who did not want an Islamic state in Syria. This included the different Syrian actors who participated at first in the revolution, starting with the leftists, the liberals and the different religions and sects, and reaching the outside world and touching on a prevailing populism due to fear stemming from terrorist operations from Islamic fundamentalists. The regime knew very well that it could not win anyone's sympathy, not even from its own sect, if it were to use its oppressive apparatus to repress a people's revolution for freedom.

The problem is that the regime spread this scenario from the start to divide the ranks of the revolution, and the military groups fighting against the regime adopted it later on. This was the result of a difference between the identity of the first activists and the identity of those on the ground.

We could add here another category of actors who adopted this version—the grey position. The color grey is not shameful as some considered. Rather, it actually describes a position: "I am not with the regime, but I am not with the opposition either."

Grey answers usually appear when the person adopting a grey position refuses to express their actual position. Grey actors have nothing in common as they are of different sects, classes and regions. It is the answer of each person who cannot defend the system and would be ashamed of supporting it; however, they are also afraid of change because they benefit from the system.

Randa Baath: 'Any cultural act is vital'

12 March 2021

Aleppo’s destruction from above

10 March 2021

Answers, in slogans and images

Symbols and slogans are some of the strongest political tools. Through their lens, it would perhaps be possible to examine the event. We will examine the messages each camp communicated through the symbols and slogans during the conflict. This could help us reach an objective assessment of what each camp wanted.

In chapter six of his book, Dr. Said Bengrad writes: "A political slogan is not artificially created by advertising agencies or political parties. It expresses and summarizes the opinion of a group of people. It is characterized by the freedom of engagement it offers. In other words, those receiving the message feel like they created it and that the message is an expression of their identity."

This phenomenon is exactly what we saw with the quick spread of the same slogans in all Syrian governorates. We also previously witnessed this when the wave of the Arab Spring slogans crossed borders. Bengrad considered slogans to be central global tools with which and through which all human needs in politics, economics, ideology, and religion would be met.

Yet, political actors have one main reason for using a political slogan. They believe people have a predisposition for ready-made ideas, categoric judgements and prejudices on which they base their short- and long-term needs, far from the concerns stemming from suspicion or the search for truth.

The first slogan launched in Syria at that time was during the Hariqa protest on February 17, 2011. Protesters chanted: "Thieves, thieves," followed by "Syrians will not be humiliated.” The regime launched no slogans that day because they were caught off guard, and so were the actors involved in the protests.

The slogans were a direct reaction to the flagrant looting and humiliation people endured at the time. Thus, the slogans emerged spontaneously to express what was in people's hearts. As for the regime, its reaction was expressed in one single statement made by the Minister of Interior at the time: "Is this a protest?! Shame on you!"

The minister's reaction was spontaneous and honest, and it was a direct expression of the regime that appointed him: any form of opposition or protest is shameful. If the figure who came to the scene was an actual actor from the regime, a head of intelligence for example, he would have directly described the protest as a crime, not just a shameful act.

The Minister of Interior did not realize the magnitude of the scandal that his spontaneous expression reflected. The same expression was greatly circulated later on and triggered sarcasm. It reflected a deeply rooted strategy in the Syrian regime's imagination which relied on the act of domesticating the opposition. The regime considered any act of protest to be immoral and shameful.

Meanwhile, the slogan "Thieves, thieves!" summarized the great pressure facing the economy. The ruling family greatly monopolized the economy through waves of privatization, especially with the "Ramrama" operation. This sarcastic term was coined by Syrians to note businessman Rami Makhlouf and the ruling family's monopoly of the economy. The economic pressure imploded in Hariqa region. The area was known as a backstage for Damascus's economic sector—commerce, crafts, workshops, shopping areas and industrial production—and the participants in the event clearly worked in the area.

The color grey is not shameful as some considered. Rather, it actually describes a position: "I am not with the regime, but I am not with the opposition either."

The second slogan, "Only Allah, Syria and freedom," had its start in the Hamidiyah market in Hariqa on March 15. One could pick up on the underlying Islamic religiosity in this slogan, which combined religion, nation and freedom. The regime immediately reacted to it with the slogan "Only Allah, Syria and Bashar.” The message was that religion could be negotiated, but freedom would remain a dream. Bashar's name replaced "freedom.”

The third slogan was: "One Syria, one people.” A slogan cannot be understood outside its context, as Bengrad notes. The real purpose behind a slogan is "not in its literal meaning, but rather in its ability to repeatedly trigger strife within a specific social context." Did the protesters want to describe Syrian people as united? If so, why did the protesters chanting the slogan experience the harshest of repressions and even murder? The slogan in fact carried a people's dream, the dream of united Syrian people. Protesters demanded equality between citizens and, at the same time, affirmed that they did not aspire for a reverse sectarianism.

The fourth slogan was raised on March 16 in al-Dakhiliyeh square, where the repression of protesters started. It had been raised a few days earlier in front of the Libyan embassy, with protesters chanting "Only a traitor kills his own people!"

Yet the regime chanted just one slogan: "Only Allah, Syria and Bashar,” which it previously shared with security personnel. This is why it was seen as ridiculous and obtrusive, and protesters did not relate to it. No one was chanting "Only Allah, Syria and freedom.” The identity of actors in the al-Dakhiliyeh protest was loud and clear.

Since the very start, attempts to tag those present as infiltrators did not succeed. The organizers of the protest had even announced themselves in a statement signed by more than 300 intellectuals a week before the protest. In the statement, they declared their support for those detained during the Damascus Spring, and they demanded the release of detainees who had started a food strike. Prisons became narrow to the point of suffocation, especially after having witnessed the Tunisians and Egyptians succeed in bringing down the dictatorships. Instead, protesters were paying for demanding democracy, and they were thrown in jail when they had not yet even demanded the fall of the regime.

The same slogans were repeated on March 18 in Daraa, where an explosion of slogans followed and spread throughout Syria. The slogan "Syrians will not be humiliated" soon turned into "Death but not humiliation", a popular old slogan. This happened after the first martyr of the peaceful protests fell.

According to Bengrad, the slogan could "extend across time. Even if it is not always effective, it is by nature recurring. Every time people are faced with the same threat, the slogan recurs like a magical incantation that reduces concern and gathers momentum.”

Once the regime left no room for negotiation and resorted to plain violence, the Arab Spring slogan, "the people want the fall of the regime,” resurfaced. Observing the regime’s slogans tells us that it never lied about its battle. Rather, the regime consistently dealt with the events. The regime's slogans reflected its true nature: “Assad or we burn the country.” Regime loyalists repeated, bluntly and insolently, their slogan: "For Assad's eyes, we will be looters forever.” This was to counter the protesters’ slogan "Despite Assad, freedom forever.”

As for the images raised during demonstrations, the main observation Syrians agreed on was that the regime only had one image in the face of protesters: Bashar al-Assad's. Meanwhile, protesters raised no images of their own until martyrs fell. After that moment, many pictures of martyrs were raised, to face the one image that was sponsoring their murder.

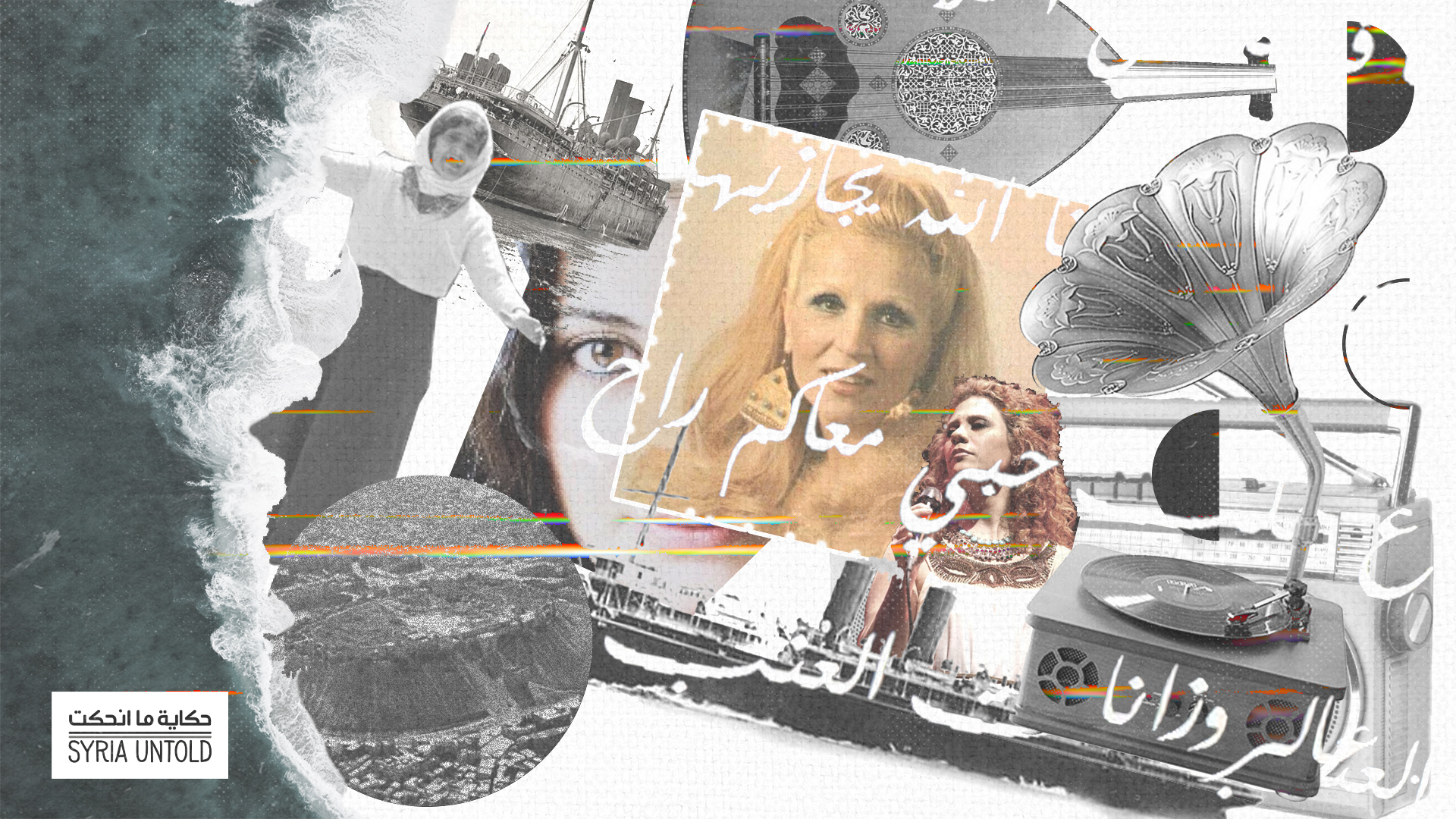

Songs of nostalgia in New York City’s long-lost ‘Little Syria’

05 March 2021

A famine, a ship and a folk song that spanned borders

18 December 2020

The window of possibility at the intersection of answers

Common points could be determined between the answers on all levels. First, a massive movement in Syria started in 2011. Second, the regime was targeted in the movement. Third, sectarian movements were involved.

Revolutionary youth who were not aligned with any ideology, religion or sect rejected the first answer. They did not adopt the "Sunni revolution in Syria'' slogan. Instead, they insisted on the revolution being a peaceful national revolution against oppression, corruption, discrimination, repression of freedom and injustice.

However, many military factions agreed with the regime later on, and adopted the narrative of a sectarian Sunni revolution against Alawite rule. Both visions—the one of the regime and the one of the fighting factions—would grow closer the longer the war lasted. Eventually, years later, the visions converged. This was after the armed conflict erupted between the military factions that deserted the regime's army on the one hand, and the regime and its army on the other. Many considered this conflict to be an extension of the revolution and a necessary passage resulting from the regime's violence.

The armed conflict was replaced with a new type of struggle, given the concentration of external factors on the ground in Syria. The parties of the conflict no longer were restricted to just the people and the regime. A regional and international war erupted, using new tools: Sunni and Shia militias.

This shift after a call for jihad was issued from every side, and fighters went to Syria to save the Sunnis. Chechens, Tunisians, French and European Muslims, Islamic State fighters and al-Qaeda fighters headed to Syria. A new phenomenon also emerged: an international mustering of Shia forces for jihad, launched by Iran to support the Shia fight against the Sunnis. Hezbollah alone was no longer enough, so other diverse Shia militias were needed. The Afghans, the Pakistanis, and the poor of the Iranian Shia answered the call. Both sides went to Syria either as mercenaries or religious fighters. This was necessary to attract human resources made up of simple religious young people to fuel the war. They are typically the victims of the emotional charge of sectarianism, and are exploited in wars that have nothing to do with religion or sect.

After filtering through the answers explaining the conflict in Syria, only two different answers are reached. The two answers did not come from nothing, as they influenced large groups of people. Thus, I believe that we must examine the intersections of both answers when approaching reality, in order to open a window of possibility in Syria's future. The intersection we could build on is the acknowledgement of the presence of a popular Muslim religious element in the revolution. It does not mean that revolution was not democratic. Every individual had different motives for participating in this revolution, just like in any other revolution. However, what largely set this element apart from the revolution was the eventual raising of symbols of the Islamic State, which divided the rebels.

Sarout, Fadwa Souleimane, and the intellectual elite

The most famous intersection between answers was the emergence of the famous revolutionary duo in Khalidiya street of Homs: Abdul Baset al-Sarout and Fadwa Souleimane. The answers intersected with most intellectuals of different sects and ideologies, taking the side of the revolution despite the religious symbols that emerged. Intellectuals by nature do not cave into populist fears, which obstructed many from supporting the revolution. We saw intellectuals support the revolution and document the violations of the regime in defiant Sunni areas. Many intellectuals were involved, such as Samar Yazbek, Rosa Yassine Hassan, Wejdan Nassif, Hanadi Zahlout and others.

Democratic and leftist writer Yassin al-Haj Saleh, who lived with his wife, political dissident Samira Khalil, in the rebellious town of Douma, supported the revolution. Democratic lawyer Razan Zaitouneh, who was among the leaders of the revolution’s coordination committees, as well as activist Wael Hamadeh and poet Nazem Hamadi, also advocated the revolution. The rift soon materialized in 2013, when Islamized armed factions abducted these four democratic activists.

In the 1960s, Syrian philosopher Sadiq Jalal al-Azm wrote the book Critique of Religious Thought, which clearly combined both explanations. In an interview with Orient TV in September 2015, he stated: "The country is saturated with sectarianism, and the instincts of revenge are uncontrollable.”

Al-Azm was clear in the interview that "Alawite politics are not the politics of Alawites as people. Alawite politics are a type of security, military, financial and sectarian structure that must fall. By saying so, I am trying to keep the Alawite sect separate." He continued: "One of the virtues of the revolution is that we can now say these ideas in the open instead of keeping Syrian thoughts about this issue behind closed doors." To him, "the backbone of the revolution is the Arab Sunni sect and the Kurdish people, while the backbone of the regime is the Alawite sect, which is supplying the men and the fighters."

Al-Azm added that this dynamic does not automatically classify the revolution as a religious Sunni revolution or even a civil war. Rather, it is a revolution for democracy and against sectarian discrimination. Hungary, for example, witnessed a revolution in 1956, but no one dubbed it as Christian, although most participants were Catholic and asking for freedom of belief. When asked, as a leftist and secular figure, if he had concerns about the religiosity of revolutionaries, al-Azm said he had none. “Popular Syrian Islam does not accept the violence seen in the practices of the Taliban, al-Qaeda, and the Islamic State. It is about worship and practices."

As for Syrian writer Mustafa Khalifa, he stated in one of his interviews: "In Syria, for the past 50 years, there has been a civil war disguised in sectarianism. No one spoke of it. Had the revolution of peace and freedom won in the first year, it would have ended this ongoing civil war" [iii].

So, what has happened for the past decade is a revolution for freedom and democracy, and a struggle against any form of discrimination. It is a general Syrian struggle for democracy. This is what gave the revolution huge power since the very start. The system fell, symbolically, in the first year. However, regional and international powers preserved its empty shell to justify their occupation of Syria.

Hence, what has happened for the past decade constituted a courageous attempt from the Syrian people to launch “the third round of national Syrian integration,” to restructure themselves as a people after being torn apart by 50 years of systematic destruction [iv].

Finally, I would like to point out Hannah Arendt's definition of a revolution, so that we do not go down the rabbit hole of eventual outcomes and problems. In her 1963 book, On Revolution, Arendt underlined that the concept of revolution is closely connected with the idea that the course of history starts again suddenly. With revolution, a completely new story that was never told before, and that never existed, is about to emerge [v].

This is exactly what happened in Syria 10 years ago. Suddenly, the course of history started again.