Read this essay in its original Arabic here.

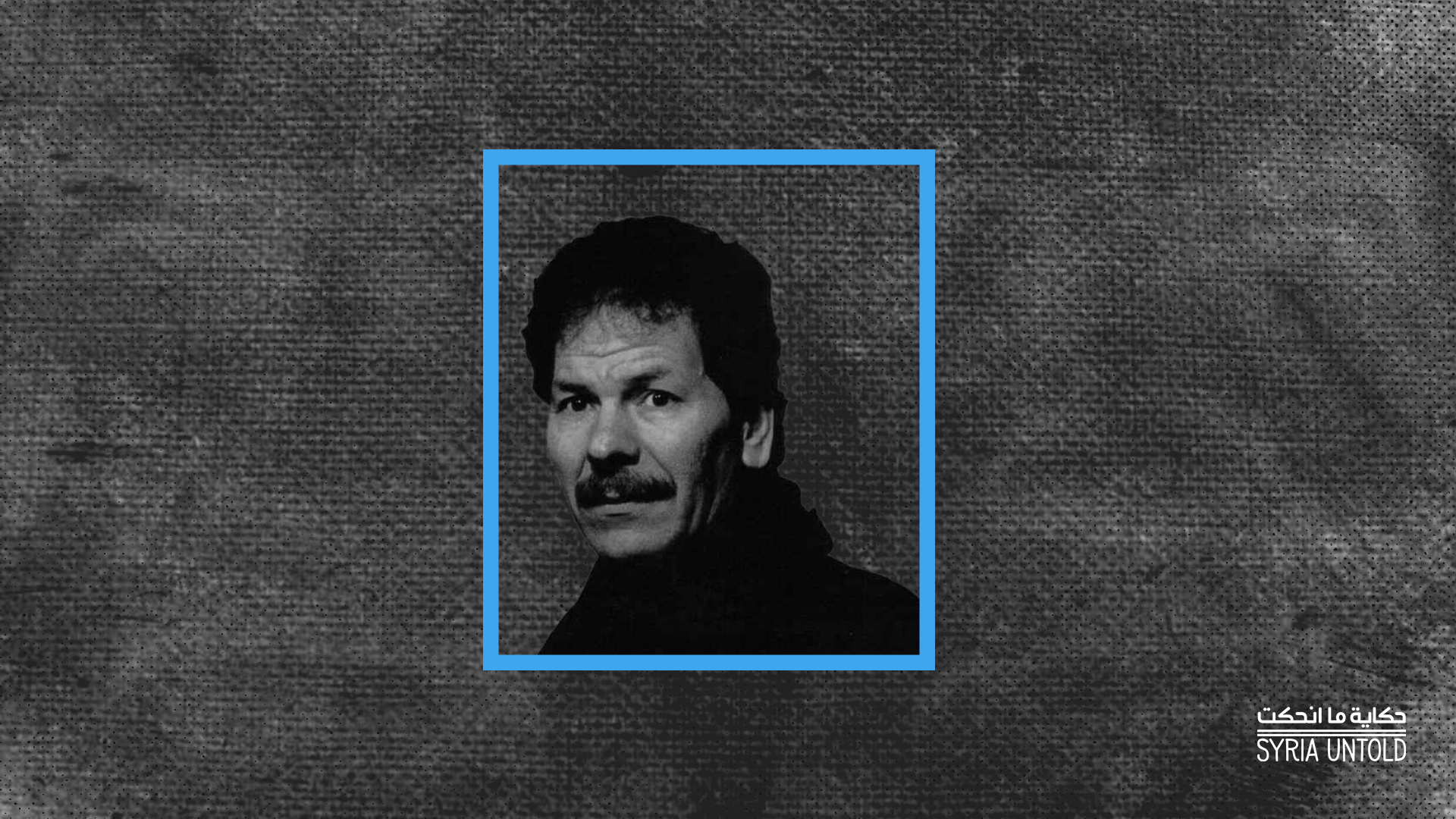

It all started when Jean René showed me the first photos.

I looked at myself, and I saw a new woman. The pictures surprised me: I’m a new person! Was I always in search of that other me, that person who I do not yet know?

That other me was now looking me in the eyes. She seemed nice; I liked her.

I usually complain about pictures of myself. I suffer whenever media outlets ask me to choose a photo, one that I almost always dislike. The reason for this, which I understood while standing there with my publisher Jean René looking at my new photo, was that none of my previous pictures looked like me. One time, a professional photographer was taking pictures of me, pictures that weren’t pretty. When I told him the photos were ugly, he responded: These are you. Then he fell silent, and I thought of the sentence that he almost said out loud before stopping himself. Am I really so ugly?

Soon, I was bombarded with photos from multiple sources: from Anne, Ayed, Nicole, Eliyanne. And they all gave me the same impression: A new person had emerged in these images.

Maha Hassan: ‘I grew up surrounded by storytellers’

18 February 2022

‘Recreating a beautiful thing’

27 August 2021

That sunny day, I was overcome with joy when I saw the negative test result, after the three previous tests had all come back positive for the covid virus that coursed through my body.

I had finally recovered and, free from winter clothes, I wore a light summer dress. With no scarf around my neck, I set out to the publishing house an hour before the book launch to make a press appointment.

Jean René decided to take a few photos of me before the journalist arrived, so that I could use them in the flyers for my book signing event two days later. The book was fresh. This was the first copy I’d seen in the flesh, the first time I’d seen it, touched it and taken photos with it. This was my new French book.

The new me: Between French and Kurdish

Only three days earlier, Nowruz lit the world with its torch, music and colors, and I was still sick with covid, forcing me to cancel a number of appointments. But two hours before the book launch, I took another covid test and made sure I had truly recovered.

It was exceptionally sunny and the meadow next to my house was glistening in the light. The flowers were vibrantly colorful, as if Nowruz had brought its renewal to France.

I felt a mixture of reality and truth. Maybe staying at home for those several days made me surprised by the warm sun, by watching the boats in the river and people’s clothes—as if it had become summer all of a sudden.

A few hours before

That morning I woke up to a phone call from my neighbor, Marie Cécile. I had given her my number when I left so that she could tell me if there were any emergencies. I didn’t answer the phone, but later I heard the voicemail she sent me: This is a big day for you. I just read about it in the newspaper, I’ll be one of the first to attend.

The Aleppo that remained in my imagination can no longer come true even in my dreams. Everything vanished.

I hadn’t told Marie Cécile about myself, and I often evaded her questions, instead answering her in short sentences. So she was happy and moved when she saw my name and picture in the newspaper. I, too, was moved and I bothered myself with imaging the same scene happening in Aleppo: I’d wake up to the doorbell. I’d find my neighbor Umm Hussein holding up a newspaper and saying: I’m coming to your book signing today! Then Umm Hussein would set off to tell all the other neighbors, just as Marie Cécile often does, reveling in her discovery of the news.

But that scene would be impossible in Syria.

Not only because Umm Hussein is illiterate, but also because she doesn’t subscribe to any newspaper. It’s not because I never held a book signing in Syria, but rather that most of my neighbors have left. Some of them died under bombs, others were taken by disease or the war’s oppression. The rest were displaced either within Syria or to Turkey and Europe.

Painting on the walls to endure Islamic State prison

03 March 2022

No, such a scene would be impossible. The Aleppo that remained in my imagination can no longer come true even in my dreams. Everything vanished.

I paid no attention to my phone as it rang alone in my purse, where I left it as I walked with the journalist to get my picture taken. The next day Marie Cécile would tell me that she couldn’t find the address, that she called me to ask where to go for the book signing, and that she returned home only to read that same newspaper headline again and see that she was more than half an hour late. She was upset, having missed much of what I said to the audience.

What I said to the audience

It was like I had moved into a new house, a big house, and these were all my friends and guests who had come to give me their blessings. The sun played the role of hostess, keeping a watchful eye on the scene, radiating a beautiful light that reflected on all our faces. The light imbued the event with a strange and new energy.

I usually feel a bit nervous about public speaking. The first few minutes, my brain is a void and I don’t know where to start. Then, the words begin to flow.

But that’s not what happened on this particular day. I wasn’t nervous, and I wasn’t asking myself what I’d say when it was my turn to speak. Even the way I sat down felt strange and new to me, as if I was sitting with my family, at ease, wearing house clothes and moving my body with liveliness and comfort.

This lack of nervousness is new to me. I didn’t know how it was born in those moments, and I didn’t think about it again until two days later when I sat down to write about it. Where did this come from, this “I do what I want, I sit comfortably and I say whatever I please”?

Where did this relaxed state come from, or rather that easy give-and-take with the audience? I didn’t feel the anxiety of needing to be understood. They understood me with no effort. This kind of relaxation during public speaking is rare for me, and the only reason I felt this way was because I was covered in sun, warmth and light—and freedom.

It was like I had moved into a new house, a big house, and these were all my friends and guests who had come to give me their blessings.

It was the relief of freedom. My words flowed spontaneously as I spoke about the women who inspired my novel, who shaped my conscience and imagination, the true heroes nevertheless left behind in darkness as the world of stories remains open for men. Women are alone in their storytelling, true and serious, narrating their tales in the home.

I don’t know how I felt then, surrounded by these women’s souls, like angels flying above us and butterflies making loops in my head, untethering my imagination and words.

I told the audience about the world of women behind closed doors, a world closed to strangers. It is a world filled with banter, joy, dancing, cooking, of creating the details of beauty. The women in that audience were happy, as were the men. They listened to this world of women, whose true face goes unmentioned in the “political” media, and may be approached only through art and literature.

Between translation and dubbing: Where do I stand?

In what language did you conceive of this novel? Someone from the audience asked me. I wrote it in Arabic at first, then translated what I wrote into French, the language in which the novel would be published.

I normally write directly on my computer, but this novel has no trace there. I wrote each chapter in Arabic on paper, then met with my friend Ismaël Dupont, who doesn’t know a word of Arabic, to translate it to him into French as he typed it all down.

In search of the best picture in the world

22 January 2021

In what language do you think? The audience member asked me again. I took a moment to think, then answered her. I don’t know, my brain processes information in multiple languages. But even the thoughts that preceded my answer ran through my head in French.

When I’m surrounded by French speakers, at an event like this one, my thoughts flow in French. The automatic translation I’m usually doing in my head when I’m planning what to write or say ceases. There is a distance between me and the French going on around me. I prepare for it in Arabic, then my mind translates for me. But when there is no distance, when I’m speaking directly to people like at the book signing, my mind doesn’t have enough time to enter the Arabic-language room in my internal laboratory; it goes knocking on the French door right away.

After the event, I was signing books for the audience. I turned to Elias, an old student of mine, and asked him in Arabic: Should I sign yours in Arabic? I noticed shocked faces around me. The audience members were astonished to hear me speak in Arabic, as if I had morphed into another person right before their eyes.

I remember my mother’s shock when she saw Polat Alemdar, the main character of the Turkish TV series Valley of the Wolves, speak Turkish for the first time. She protested: Why doesn’t he speak Arabic like he does in Syria? My sister responded to her in jest: When he goes to Syria, he speaks Arabic, and in Turkey, he speaks Turkish.

It wasn’t easy to convince my mother that Polat Alemndar actually speaks Turkish, his mother tongue, and that the Arabic she had heard in Syria was just dubbed by another actor.

In those moments, was I playing some role in a dubbed TV drama, when the audience members heard me speak Arabic for the first time? I don’t know. But they very kindly started asking me to write some words in Arabic in the books they had brought to the signing, even if they didn’t understand what I was writing; they said they’d find someone to translate for them later. Some of them voiced their astonishment as they saw my hand move across the page from right to left, rather than the left to right I had been signing previously.

Where did this come from, this “I do what I want, I sit comfortably and I say whatever I please”?

The opposite of a Kafkaesque metamorphosis

In the same way that I “Frenchify” my entire world, the way that people paste a text into a Google Translate box, I took the Arabic-speaking characters of my novel to the French portion of my brain.

It was a transfer between two salons: that of the French women here with me at the book signing, and the second salon tacked onto the first, where the Arab and Kurdish women sat. I felt like a butterfly landing someplace seen, though coming from some other, unseen, place, where the souls of my novel’s characters gathered.

This butterfly, which had just emerged to spring sunshine after Nowruz and covid recovery, was a new being emanating from my very body—a being I cannot accurately describe. It wasn’t a translated version of me, not dubbed or even pirated. Maybe I was the one who was asleep, who planted this seed that needed time to grow, become green and bloom into spring.

It was like I grew new skin beneath the old, like springtime peeled away my personality and a new one appeared, succulent, its head outstretched toward the world.

That calm new woman slowly advanced. She was brand-new, relaxed, honest. She didn’t fear anything, become nervous or feel the need to justify herself.

I hadn’t woken up and found myself a cockroach. Rather, what happened to me was something that Kafka had never anticipated: My entire world of reading, of anxiety and the desire to break free of that anxiety, and all my accumulated years of writing, it had all presented me now with a reassuring woman. A woman born from a seed of nerves.

I didn’t turn into a cockroach; I had become a butterfly.

Does this metamorphosis happen only to women?

Thoughts on exile in Germany

17 July 2021

The body, between event and memory

25 January 2021

I invoke Kafka with love and gratitude, even as I imagine that his masculinity itself was the reason he felt so emasculated. But today is different from his time, and Kafka didn’t tell us about the condition of the butterfly so as not to damage our imaginations.

My French skin

When I obtained a French passport more than a decade ago, I felt the freedom of travel. Still, I didn't feel that it granted me some sense of belonging to France, or that I had become French anywhere other than on paper.

But what happened to me that first day of my book launch, and in the following week (happy readers, book signings, the letters I received) created a new umbilical cord connecting me to France. Writing, and the publishing of that writing, is a cord that cannot be broken.

French people won’t be able to deny it. And I no longer care what they think of me, or how they see me. The mirror of identity into which I had been staring all those years in exile had vanished. I no longer care to ask that frightened girl: Mirror, tell me, is there a woman more beautiful than me? I mean: Mirror, tell me, what are the results of your analysis of where I belong?

My sense of belonging to the land that published my book, the land in whose language I wrote it; that is belonging.

My publisher, Jean René, believed in me, and when he received my manuscript he felt the joy of a father listing his children’s successes in life.

I felt an unexpected kinship with Jean René, like I had crossed from exile to home.

Completing the circle and melding existence

During that first week after my book’s publication, I received tons of messages. The most impactful was from Patrice, whose letter was only the start of a longer exchange, and which generated ideas for new projects and proposals.

Patrice agreed with the publisher to set aside a day for me within a multi-day arts event so that I could discuss my novel, alongside readings by a professional actress.

I felt a melding of my existence, that my life today is an extension of my life that began in Aleppo and moved onward to France.

Patrice hadn’t yet read my novel. When he did, he wrote to me and said something out of context. He wrote about Jacques Fache, whom I mentioned in one of my previous novels, Umbilical Cord, which I published more than a decade ago. He was a poet who met fellow writer André Breton in Nantes after the end of World War II, later dying in a hospital there. I consider Fache to be the true founder of Surrealism. But as it always goes, there are stars that shine and others that nobody ever sees. Breton became the shining star while Fache died young, nobody having heard of him except his close friends and relatives.

At one point, Patrice said that at the age of 16 he had founded a group in Nantes under Jacques Fache’s name, and he told me at length what this poet meant to him. Then he suggested that I devote some of my time at the arts event to talk about “how I discovered Jacques Fache.”

I was a young woman when I stumbled across a book about Surrealism by Michel Carrouges, translated by Khalida al-Saeed. I was drawn to the character of Jacques Fache.

Again I felt the bliss of literature: Some 30 years ago in Aleppo, I fell in love with Jacques Fache, without imagining that I’d ever come to France and meet French people who knew his story and loved him as I did.

I felt a melding of my existence, that my life today is an extension of my life that began in Aleppo and moved onward to France.

In an interview a few months ago, I spoke about my novel, and about reincarnation. I have a personal legend that I carried the soul of André Breton, who died when I was born!

I look at the photos Jean René sent me once again. I feel that I was born here that day, then born in Syria, and again here in France.

Every day I meet dozens of new readers interested in my novels. I’m overcome by new feelings: that every encounter is really the second and not the first. I’ve met them all before, I knew them and they knew me, only we forgot one another so my novel came along to reacquaint us.

I walk through the city with a surprising sense of belonging, and I see copies of my novel in the storefronts. My eyes catch the title, the “New Release,” my name as the author. Where, then, does a writer belong, if not the land in whose language they now write, where they publish, and where their books are displayed on shop shelves and in window displays?

Am I now free from the curse of exile?

I need some time to test my new personality, my new self. Fingers trembling, I feel two little wings pop out from behind my armpits as if I’m preparing to fly—a big, colorful butterfly protected by the power of writing, not a cockroach exhausted by it.