Read this interview in its original Arabic here.

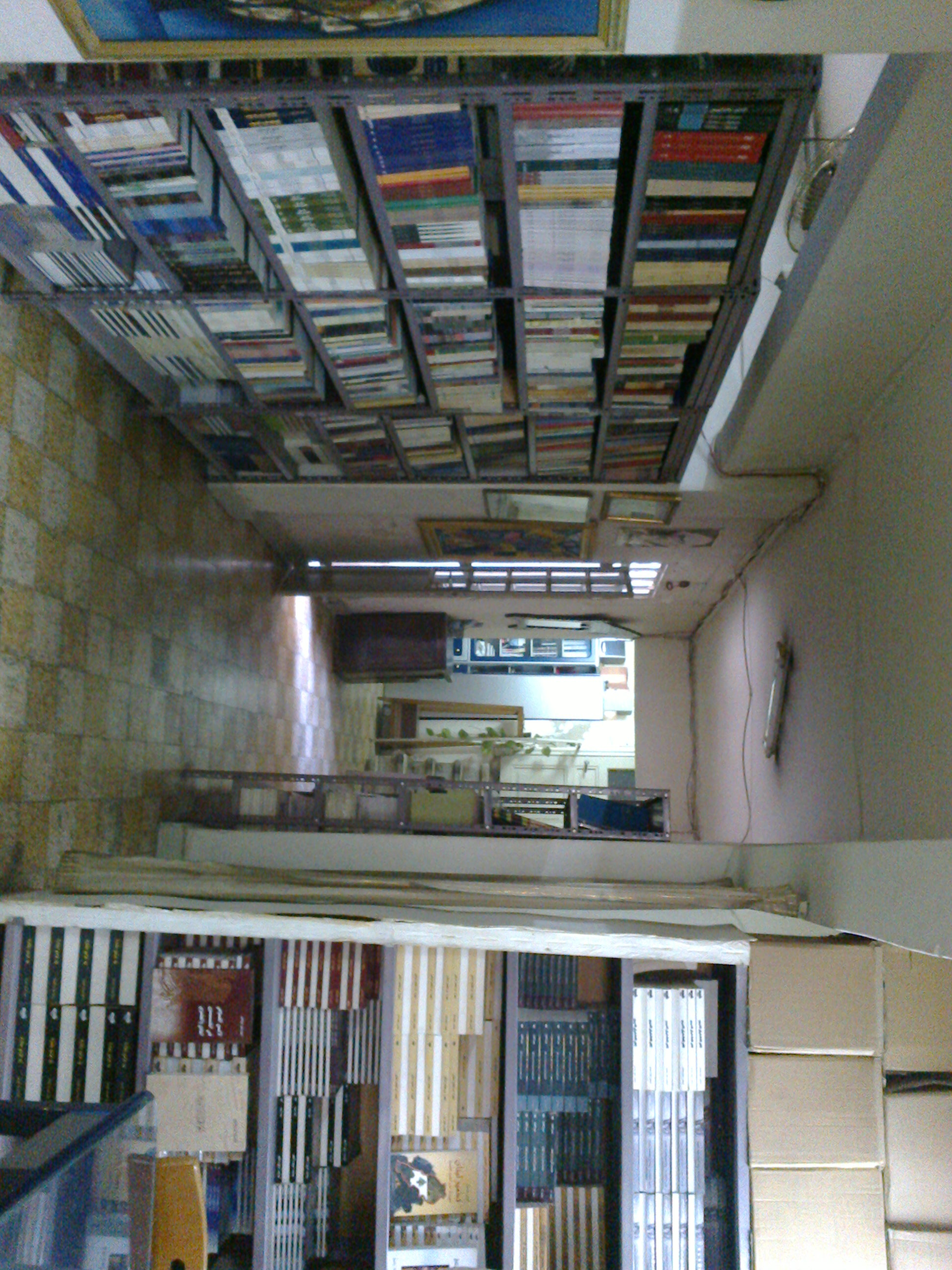

A short staircase leads me to the basement of an old building just off of al-Abed Street in Damascus. An airy, transparent darkness engulfs the hallway and the entire publishing house, enough for me to feel joy. When I see any stack of books, I don’t care how the authors found their passions or played cards; I see only their remarkable work.

“We want to express something complex and grand, and in the end all we say is I love you,” the Argentine-Canadian writer Alberto Manguel, who cherishes the art of reading and books, once said. Something complex and grant, and in the end, “I love you.” That is the joy that keeps regenerating itself in my heart, moving and growing. A joy that matched the contents of the books I’ve read.

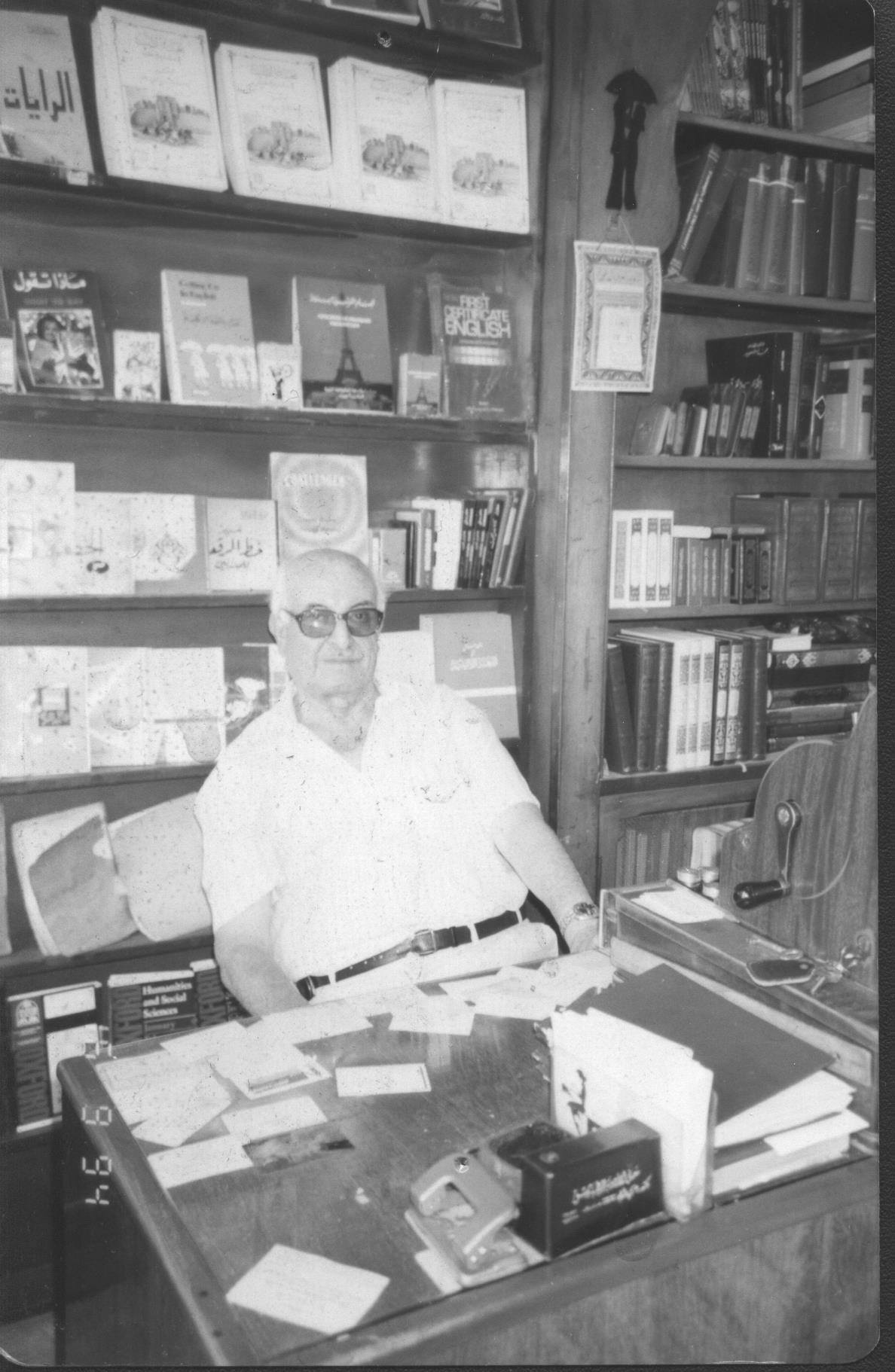

Samar Haddad guides me into her office, which contains objects, photographs, bits of writing about her life. She tells me about the people who have come and gone and whose ghosts remain here, adrift. I sense sounds, but I don’t understand everything. I don’t have time to create my own little world; no, I’m too busy with SyriaUntold and pinpointing the story Dar Atlas, the publishing house that Samar now runs in Damascus, after inheriting the business from her father. How will Dar Atlas, which dates back to the 1950s, stay afloat? How will it take on new projects, some of which have come and gone in a flash and others which disappear altogether?

‘Recreating a beautiful thing’

27 August 2021

Maha Hassan: ‘I grew up surrounded by storytellers’

18 February 2022

I know that the best person to talk about this room, its walls stacked with little papers and and old photographs, the lives of all the books and their journeys across borders—that person is Samar Haddad. Her words flow, a flood of sadness and reflection, memories that kept those physical books alive. “A book is life,” she says. “It must remain, despite everything.”

Amid the economic crisis in Syria and the rise ebooks, are physical books dying out?

This question is problematic, and quite heavy. It’s a question we asked ourselves 20 years ago. Imagine! Since 20 years we’ve been saying: The book is supposed to be dying. So, die. But it still hasn’t. It always returns instead to its youth, defying its artificial [fate]. It transcends itself to become a revelation, something that the world sees and reads.

Take, for example: physical book fairs still exist. Each fair has dozens of booths, and each booth hundreds of books. That’s just one example of how the physical book is alive.

When I say “book,” I mean what I say. Not all books deserve the word. Do you understand what I mean? There are many books, and huge amounts of money have been spent to them. I don’t want to name names, but there are book fairs here and there that are notable solely for how they look: the building, the architecture, the design, the installations and decor. One book on their shelves may equal my budget for an entire year. Just one book, without substance. Without form, without output. In short, it’s an ugly picture. This is something very, very sad.

Exaggerated decorations, celebrations, book signing parties. Readers flocking to buy. Luxury designs and empty substance produced by the nature of the present. The result: no cultural or intellectual information, but rather a trent towards flattening, shortening, distorting. Form without substance.

Didn’t you say just a little while ago that books open up a world and a life of knowledge to you? This is the substance that I’m referring to: the complete transcendence of the bitter cultural reality through physical books.

Books are freedom and reading is what frees us. The true publisher, whether small, medium or large, is the freedom fighter of our age. As a publisher, I’m a resistance fighter in this age of consumerism.

Any small publisher (including me) suffers from various disputes, sanctions, the electricity crisis, and from the simplest things that arise in life. All these things cause a sense of shock and disappointment in your soul because of the irrational rupture and distortion that has befallen us. Despite all that, we print, publish and market beautiful books (beautiful both in form and substance), something that makes us proud. Of course, the same applies to many of my colleagues both inside and outside Syria. We have the capacity to keep going.

And so, though we keeping hearing over and over again that “the physical book is dying,” I still say: “No it isn’t.” That is, so long as there are people demanding physical books, people who take into account the clear difference—for them—between the physical books both good and bad, and electronic books.

Youssef Abdelke, Mouneer al-Shaarani and others design the covers for our books. I do not accept for a book with good substance to appear without an equally good design, just as I don’t accept any errors within the book. The book in this sense is an artistic form, and it is within this artistic truth that the book endures.

During our conversation earlier, I mentioned the book Les Célibataires de l'Art, and the errors inside of it. I was upset. Our first steps are to do three rounds of edits on each of our books, and then comes the proofreading. Basically, the book goes from the author or translator (its first draft) to the editor and then to the proofreader. If there are any further comments, then the book goes back to the author, who has the right to reject whatever they see fit, outside of syntactical or grammatical errors. This all happens before the book goes to print; these multiple re-readings.

We strive for perfection to the extent that we can, for something resembling intellectual satisfaction and beauty. Nobody works like this. Very few Arabic-language publishers work with this approach, one that has respect for serious readers. Despite our method, our sales inside Syria are at a loss. That’s because we are, first and foremost, a Syrian publishing house and since the beginning we have been oriented towards Syrian readers.

I said “loss” because we are unable to increase the prices of our books. The reason is, simply, that people are dying of hunger. We try to compensate for these losses through our book exhibitions abroad.

In short, I don’t agree with the idea that physical books are dying, regardless of how deeply our lived reality deteriorates.

Dima Alzayat: Grappling with Arab ‘Americana’

10 February 2022

Returning to Abu Alaa al-Maari in our year of plague

13 May 2021

Tell me about the diversity of the books you publish. What are these books’ histories in terms of writing, printing and publishing?

It is said that all books of all types have their share of presentation and marketing. This is true of all commercial books, whether they are cookbooks, horoscope guides or even yellowbooks—the distributor or the publisher has no right to act on behalf of the reader, to divine what the reader wants, likes, doesn’t want and doesn’t like.

This is bibliodiversity, which brings us to another topic, that of the justice of expression vs. freedom of expression. Freedom of expression gives and displays the strongest voices to the strongest readers at the expense of marginalized voices. Meanwhile, justice of expression gives light to all voices, including those of books published by independent or self-funded publishing houses.

I choose the bibliographic catalogue that suits me, and I face difficulty from the censorship officers in obtaining the rights to publish books without deleting or adding certain parts.

We’re still producing books, and we’re thinking about upcoming projects. We’re working on a book called The Encyclopedia of Arabic Calligraphy with the help of calligrapher Mouneer al-Shaarani, and another book of excerpts from Ibn Arabi. This book has also been translated into other languages (French, English and Spanish) and includes artwork and an introduction by Mouneer. We also have four books translated into Arabic from German, Catalan and English.

I mention these projects to say that I don’t believe books are dead.

You seem to imply that the goal in book publishing is not to profit. Is the purpose, then, to seek knowledge? How is it possible to continue towards this goal without profit?

As I said previously, we have been oriented since the beginning towards the Syrian audience and the Syrian reader. That is, we take the Syrian reader into account.

Are the prices for books outside Syria different that those you sell inside Syria?

Yes, very different. We participate in at least eight book fairs per year. The income we gain from sales at those events outside Syria helps us to stay afloat here. We also rely on grants to translate books from various languages into Arabic as part of what you could call “cultural promotion”: promoting French, Catalan, Spanish and German, for example. These grants fund at least 70 percent of our project.

It’s rare to hear someone, the owner of an organization, speak more about cultural and intellectual values than about profits and income.

Exactly. I concern myself with culture before profit-making as a publisher. Publishing is, in the end, a business venture, and lacking cultural concerns does not negate its sanctity. If you wanted to, you could turn your focus more to the business side of things and make great profits.

Do you worry that the books Dar Atlas translates into Arabic are culpable of linguistic “betrayal” via translation? As a publisher, are you concerned about the translated text matching the original? As you know, translation serves to welcome the stranger; translation is istening, dialogue and interaction with this other. Do you view translation in this framework?

Of course. Without a doubt, I try to achieve a translation that is true to the original to the highest degree possible. However, there can be no “betrayal” in a true sense. Rather, there are certain choices that the translator deems appropriate in context.

Do these choices stem from the nature of translation itself, or from the translator’s personal perspective?

Sultana’s story

10 July 2021

From the requirements of the text, or the structure.

Does this apply to all translators?

No. There is no translation that is 100 percent perfect. Rather, there is a set of ethics for translation. For example:

Adnan Jamous translated Dostoevsky’s A Writer’s Diary and did an incredible job. When I read his translation, I felt as if I was reading the book in its mother tongue. Adnan had been translating the book for nearly a decade, and is now 80 years old. And so, I cannot say that he has betrayed Dostoevsky, not at all. I must also add that we are very keen to work with highly skilled translators, despite their high rates.

Another example: Nabil al-Huffar is among the most important translators, both in Syria and abroad. He translates from German to Arabic. His translations have, in essence, the “perspective of distance,” a beautiful phrase that I borrow from a wondering poet to describe Nabil’s moral and aesthetic expressiveness.

Finally, I read a text by Amin Maalouf in the original language and I noticed the difference: The translated text doesn’t have the same degree of beauty and luster as the original.

Maybe we are lucky to have translators with good knowledge of language, transmission, culture and interaction with others.

Tell me abut your recent book exhibition in the Zawaya Art Gallery in Damascus, which featured books alongside handicrafts from various regions of Syria. What is the relationship between physical books and handicrafts?

We wanted to highlight the cultural dimensions of various partner projects and place them in their context. We provided the opportunity for the directors of these different projects (who, coincidentally, were all women) to talk about their experiences within the mixed atmosphere provided by books, which are carriers of culture and knowledge.

Maybe we limited the size of our audience in one way or another—I don’t know. But the experience was very successful, and we’re thinking of repeating it in other parts of Damascus.

Do you feel any disappointment at the current cultural scene in Syria?

Of course. What can you expect amid this reality we’re living through?

I apologize for this next question, but I must ask. Just as you preserved your late father’s mission—that is, to keep Dar Atlas going—is there someone who will keep that same mission going when you’re gone? What is the eventual fate of Dar Atlas?

There is nobody, and no heir. I’ve been thinking about this for a long time.

Again, sorry for the sensitive question.

No no, it’s totally fine. It’s a natural and fateful thing to ask.

There are several options. I could hand over the publishing house to a competent and honest person so that it can stay afloat. However, there’s nobody I can hand it to from my own family, as my sister and I are both unmarried. I have a brother, but he’s not involved in Dar Atlas at all. The whole rest of the family is in the diaspora, given that we are of Palestinian origin.

Yes, this issue bothers me, and I’m thinking of an alternative plan. I don’t know yet. I haven’t yet started the process of handing over Dar Atlas to anyone, as I’m still able to manage everything and follow through on projects.